Lice has a deep-rooted history that has been rich and beautiful in many ways, but has also brought disasters that have left the area in ruins. Each time, the district has found a way to rise like a phoenix from the ashes.

It was the 1975 earthquake that brought about the most radical change in Lice’s history, dividing its before and after as Old Lice and New Lice. Süreyya Işık, a history teacher from Lice, takes us through the history of her district and explores its present in relation to its past.

As a native of Lice, a locale where destiny and misfortune are inextricably linked, it is challenging to narrate its history, particularly when its past is divided into two distinct eras: Old Lice and New Lice. The ancient district of Lice is a generous geography where tolerance and fraternity are paramount, hosting a multitude of cultures and civilisations from the past to the present. In this account, I will attempt to describe my hometown Lice from a social history perspective as a historian.

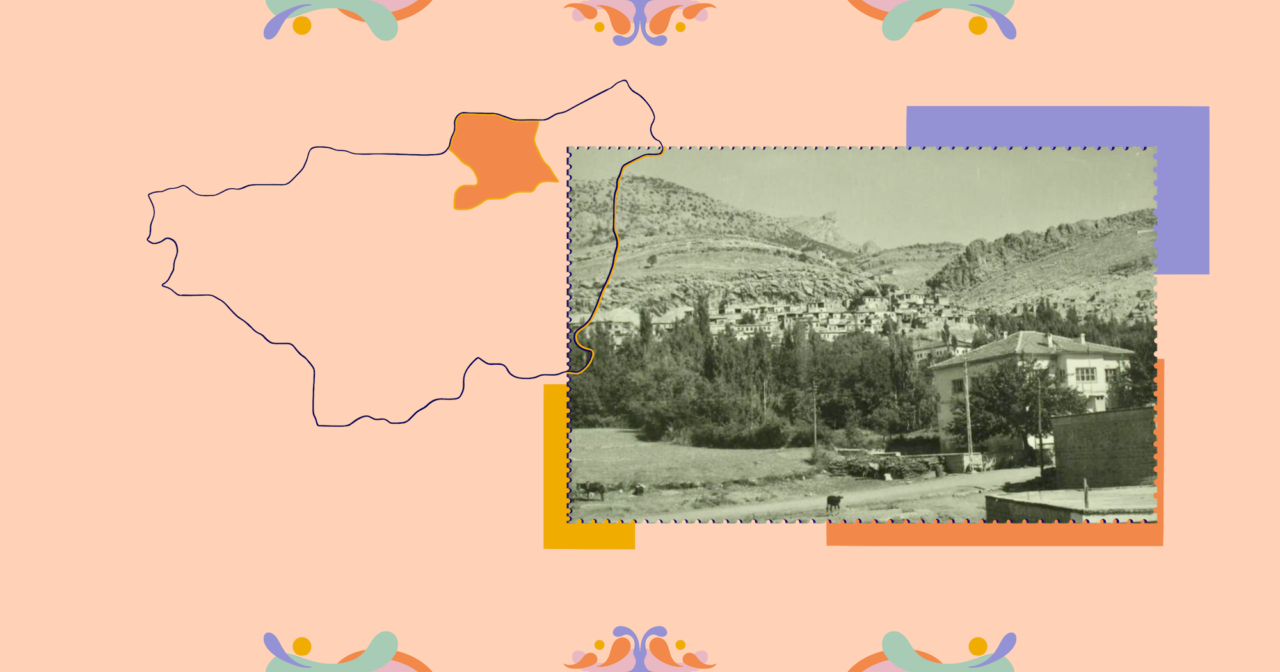

Lice, one of the 17 districts of Diyarbakır, has a history dating back to 7000 BC. It is located at the southern foothills of the Southeastern Taurus Mountains, spanning both the Southeastern Anatolia Region and Eastern Anatolia Region. The district is bordered by Kulp to the east, Silvan to the southeast, Hazro to the south, Kocaköy to the southwest, Hani to the west, and Bingöl province and Genç district to the north and northwest. The district is encircled by four mountain ranges, which include Koz, Cirbir, Lis, Adem, Kuç, Şağur, Mizak, Bebek, Ashab-ı Kehf, Zırıht, Cun, Piraziz, Nerib, Dakyanus (Decius) and Derhezan mountains. Following the earthquake that occurred on 6 September 1975, the district was relocated from its original position in the foothills to the lowlands. Consequently, the area that was inhabited until this date is referred to as Old Lice, while the section that was relocated subsequently is known as the Lice Centre.

Lice has a lengthy history and has been the site of numerous civilisations. Its first mention in Assyrian sources is as Şirişa. This earliest historical reference dates its history back to the Hurrians and Mitannians. The Assyrian domination, which brought an end to the Hurri-Mitannis, endured for a considerable period. Following the decline of the Assyrians, the local principalities of Nerbi (Nirbi) and Kelhi exercised control over their respective territories for a period of time. Subsequently, the region was subject to the rule of the Median, Persian, Macedonian, Parthian and Roman empires. During the reign of Caliph Umar, Islamic armies under the command of Ayyadh ibn Ghanem conquered the Lice (Atak) region. This marked the beginning of the Arab-Islamic period, which lasted through the Umayyads and Abbasids. Subsequently, the Seljuk Empire, Shah-Armens, Artuqids, Ilkhanids, Ayyubids, Timurid Empire, Aqqoyunlus, Safavid Empire and finally the Ottomans ruled in the region.

The Atak Zirqî Principality of Lice, with origins dating back to the Middle Ages and centred on Atak (Entak), was incorporated into the Beylerbeylik of Diyarbekir as one of the Ekrad (Kurdish) sanjaks following the establishment of Ottoman sovereignty in the region following the 1514 Battle of Chaldiran. Due to various reasons, including the inability of Atak castle and its surrounding area to accommodate the growing population, the ruler of Atak Zirqi, Ahmet bin Mir Muhammad (Vakıf Ahmet Bey), established a new settlement in Lice. This was a strategically sound decision, as Lice was also located in the Atak region, had plenty of water and was suitable for development. Furthermore, the ruler settled the people he brought from neighbouring regions in Lice.

Ahmet bin Mir Muhammad, the bey of the Atak Zirqîs who established the town of Lice in its present location, had combined all of his assets under the umbrella of the Vakf-i Masjid and Madrasa-i Zaviye-i Ahmet Bey, thereby making them available for the benefit of the community of the region. For this reason, he was popularly known as Vakıf Ahmet Bey. According to Sharafnama, a primary source of Kurdish history, Ahmet bin Mir Muhammed (Vakıf Ahmet Bey) is a descendant of Sheikh Hasan Ezraki (‘Zarraqi’). The source states that Sheikh Hasan Ezraki originated from Damascus and initially resettled in Mardin. During the Artuqid period, he relocated to the Lice-Atak region. His tomb is situated in the Derhust (Dibek) village of Lice.

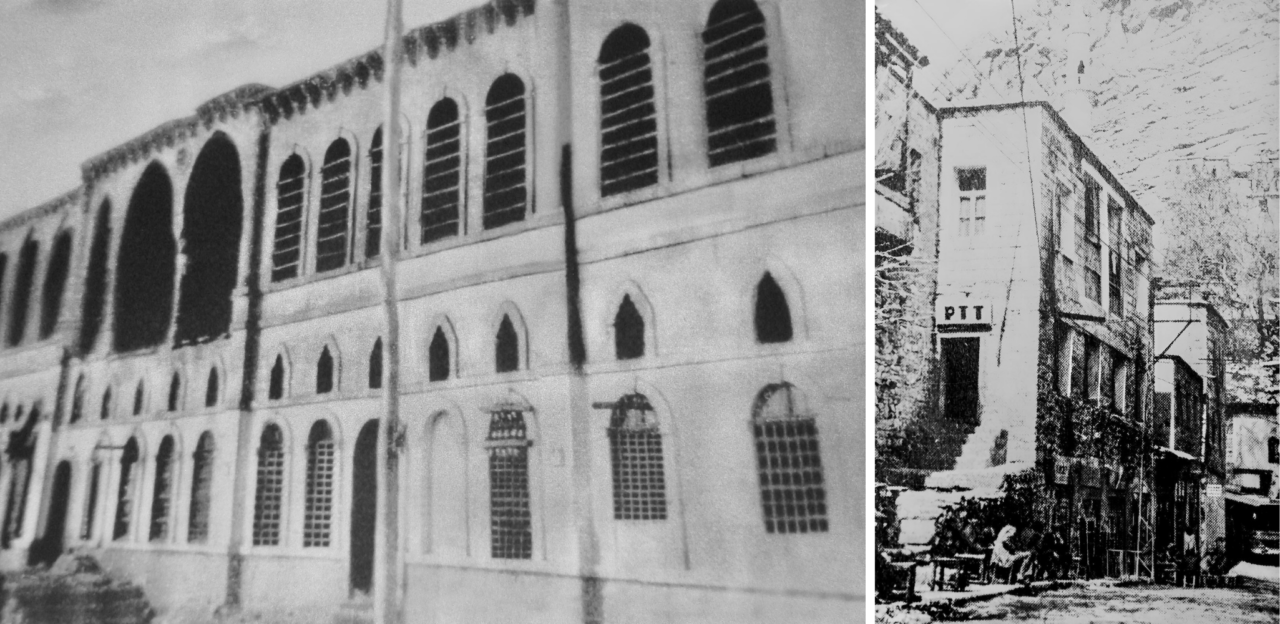

For the town of Lice, situated at the foot of the Şiro (Şirişa) River, with twelve neighbourhoods centred around the Camikebir quarter and the Vakıf Ahmet Bey Mosque, the 1975 earthquake marked a pivotal moment in its history. Its mosque, madrasah, zawiyah, hammam, historical fountains, churches, staggered houses and the Mehmet Bey Palace (Sara Mihemed Begê), which was renowned in the region, were destroyed, and significant losses were incurred. Consequently, an era came to a close, and the region of ruins was henceforth known as Old Lice.

Immediately following the earthquake, Lice was relocated to the lower plain, retaining the same neighbourhood names (Camikebir, Çarşı, Delvan, Kali, Karahasan, Kelvan, Körtük, Molla, Müminağa, Şaar, Yenişehir and Muradiye-Hıncıs). Currently, Yeşilburç (Dercimt) has been incorporated into the aforementioned twelve neighbourhoods.

In contrast to other areas within the region, the presence of clans and tribalism is notably absent in Lice. The population of Lice is characterised by large families, which are known by their own distinctive nicknames. Although the Kurdish population is the majority, the region has a history of coexistence with other ethnic groups, including Armenians, Orthodox Assyrians, Turkmen, and Arabs. To this day, the village of Sınê (Oyuklu) remains home to families who continue to speak Arabic.

Likewise, the areas of Cum, Fum and Sarnis were notable for their high population density of Armenians. While Muslims in Lice were engaged in agricultural and animal husbandry activities, Armenians were engaged in a number of crafts, including blacksmithing, tinsmithing, weaving, shoemaking, saddlery, leatherwork, and pottery (in Herbakne village). The aforementioned crafts were transmitted from Armenian masters to the Muslim population in a master-apprentice relationship.

Lice’s location on a historical trade route, situated within the geographical context of Upper Mesopotamia, has bestowed upon it a distinctive strategic importance. Due to the mountainous terrain and limited land suitable for agriculture, the inhabitants of the region traditionally engaged in the transportation of goods using beasts of burden, such as horses and mules, as a means of livelihood. The term ‘mekkâreci’ is used to describe individuals who would leave Lice for Syria, Aleppo, Damascus (collectively known as ‘Bıne Hatê’, or ‘Bınhet’) and Iran. They would cross the border illegally in order to smuggle goods, including silk, various fabrics, gauze, quilt covers (atlas), cigarette paper, tapestries, shawls, henna, jewellery and ornaments, and other necessities. This perilous trade, undertaken at the risk of death, earned the people of Lice a well-deserved reputation. In the eastern and southeastern regions, the mekkârecis and smugglers were known as the ‘Suvarê Lici’, or Lice Cavalry.

The following lines, as expressed by the celebrated poet from Diyarbakır, the late İhsan Fikret Biçici, in his poem, are perhaps most pertinent to the context of Lice: “It is our destiny that has misrepresented us / We are among those who defy the wheel of fate”

The recent history of Lice has been characterised by three significant turning points. The first of these events was the 1925 Sheikh Said Rebellion, the second was the 1975 Lice earthquake, and the last was the evacuation of villages and forced migration that began in 1993.

Lice played an active role in the 1925 Sheikh Said Rebellion. Hakkı Bey of Lice, who commanded the eastern wing of the Diyarbakır front, as well as his uncle Hüseyin Bey and the notables of the district, participated in this rebellion with their cavalry. In addition to Hakkı Bey and his uncle Hüseyin Bey (Işık family), Lice Mufti Abdülhamit Efendi and his son Sait Efendi (Atak family), who were among the notables of the district, were subjected to trial and subsequently executed by the Eastern War Tribunal. Hakkı Bey was executed in Harput (Elazığ), Hüseyin Bey in Diyarbakır Dağkapı Square, Mufti Abdülhamit and his son in Lice, while Ali Agha (Özyıldız family) was killed in Lice. Subsequent to the rebellion, the Beys of Lice (Işık family) were exiled to Kayseri, Konya and Istanbul. They were only able to return to Lice following the granting of amnesty in 1950 during the Democrat Party period. In his work Şehnama Şehîdan (The Book of Martyrs), the celebrated Kurdish poet Cegerxwîn includes the following lines about Hakkı Bey, who was executed at the age of 32, and Lice:

O Hakkı Bey of Lice, arise from your place of repose

Now storks sing in your land, where hawks no longer dwell

There are no lions left in your hometown

Now it’s time to hunt for owls¹

The second pivotal event for Lice was the 1975 earthquake, which resulted in 2,384 fatalities and the destruction of the district centre. The third significant event was the forced evacuation of the Lice centre and its villages following the assassination of Brigadier General Bahtiyar Aydın in 1993. During this period, in addition to the loss of life and property, serious changes were experienced in the demographic and social structure of the district.

Having endured a series of significant hardships, Lice was able to emerge from each subsequent challenge with resilience, akin to the mythological phoenix. The district, which continues to face significant challenges to its survival, is striving to sustain its existence whilst upholding its distinctive traditions and customs.

¹ “Licî rabe, ji cî rabe Heqî Beg / Li şûnbazan dixwînin hacî legleg / Welatê we xela rakir li şeran / Niha seyd e ji bo kundê şikêran”

Lice is a town with a rich history and a plethora of cultural and natural attractions. The region boasts a number of significant historical sites, which are of interest from a number of perspectives, including those of faith, nature and cultural tourism. Notable attractions include the Vakıf Ahmet Bey Mosque, Atak Castle, Atak Minaret (Melik Adil Mosque), Atak Bridge, White Monastery, Seven Sleepers’ Cave, Bırkleyn Caves, Çeper Castle (Dhulkarneyn) and Çeper Inn, Sinê (Oyuklu) Village Tomb and Derhust (Dibek) Village Sheikh Hasan Ezraki (Zarraqi) Tomb.

The Bırkleyn Caves, which served as an important station for Assyrian trade colonies in the past, are situated in close proximity to the Korha (Abalı) Mountains and along the Bırkleyn Stream, which constitutes the second branch of the Tigris River. With its steles and inscriptions, as well as caves purported to be beneficial for respiratory ailments and respiratory distress, and ice-cold water, it is both a historical and a tourist destination of interest.

Situated 18 kilometres from Lice and at an altitude of 1100 metres, the Decius ruins are located in the Fis/Efsus area and comprise the palace of Decius. It is one of the historical sites that merits a visit for those interested in the Hellenistic and Roman periods.

The historical sites of Atak Castle, Atak Bridge, the Melik Adil Mosque ruins and the Sahaba Tombs in the Atak/Entak region, which is the oldest settlement in Lice, are among the most notable attractions in the area.

Additionally, the Çeper Village, Çeper Castle and Çeper Inn, situated along the route from Diyarbakır to Lice to Genç, are of interest from an archaeological perspective. Given their location on the historical trade route, both structures are regarded as key strategic points within the region. It is thought that Çeper Castle was used by Alexander the Great during his eastern campaign, while the nearby Çeper Inn (caravanserai) was constructed during the reign of Murad IV.

The Vakıf Ahmet Bey Mosque, situated in the Old Lice district, was constructed by Vakıf Ahmet Bey himself, who was the Atak Zirqî Bey of Lice. Vakıf Ahmet Bey, previously referenced, commissioned the construction of the Shafis section of the Great Mosque of Diyarbakır in 1529. In 1540, he oversaw the erection of this mosque, which bears his name, over the Şiro (Şirişa) Stream by constructing an arch across the stream. The mosque and madrasah served as a centre for the training of scholars, and many of the leading figures of the period resided and taught here. One such individual is Molla Ahmedê Xasî, the author of the Mawlid-i Sharif in the Zazaki language. Following damage sustained in the 1975 Lice earthquake, the mosque was restored by the General Directorate of Foundations, Lice District Governorate and Lice Municipality in 2021, with the objective of promoting tourism.

Lice is a district that is characterised by a climate of tolerance, which extends to all members of the community, regardless of their beliefs. It is also a district with a strong sense of faith. It is a widely held belief that the tombs and shrines situated on the three hills that dominate the district of Lice serve to protect it. Those who do not have children visit the tomb of Sheikh Tangur, those with mental health issues visit the tomb of Sheikh Abdullah, and those with specific wishes visit the tomb of Sheikh Bilal, a deer herder who is said to be able to communicate with deer.

I recall from my childhood memories that on the evening of 21 March, as the sun set and darkness fell, the people of the district would direct their gaze towards the three hills where the tombs and shrines were situated, as well as other locations such as Cum, Fum, Kâş, Kevrâ Kelê, and Kevrâ Teyrân, awaiting the lighting of the Newroz fire by the younger members of the community. The sight of the fires was interpreted as a sign by each neighbourhood, which proceeded to light its own fire accompanied by dancing the halay, in imitation of the dominant hill. These inter-community fire games would not persist for long because with the approach of the gendarmerie, all would retreat to their homes, leaving aside the fires outside.

The Seven Sleepers (Ashâb-ı Kehf or Sadülkêf) Cave is another popular tourist attraction in the region, with a particularly high number of visitors on 28 May, which is observed as the ‘Awakening/Resurrection Day’ by the local population. On this day, prayers and sacrifices are offered at the site, which is located between the ancient city of Decius and the village of Duru (Derkam/Deyr-i Rakim). According to the legend, Yemliha, Mislina, Mekselina, Mernush, Debernush, Shazenush and Kefestatayush, who held senior positions in the palace of Decius, incurred the wrath of Decius for opposing the pagan beliefs. While attempting to evade capture, the Seven Sleepers sought refuge in a cave with their dog Qitmir, where they remained concealed for 309 years. It is notable that children in the Lice region can be named Yemlihan, a name that commemorates Yemliha, one of the Seven Sleepers.

The awakening nature of Lice with springtime rains (çılêsır) is especially noteworthy due to the fertile soil and clear skies that contribute to its distinctive beauty. This period of abundant greenery offers visitors a unique picnic environment. Old Lice, Cum, Fum, Hıncıs and Samparus are significant recreational areas, notable for their diverse flora.

The indispensable element of these picnics, known as ‘çixarî’ in the region, is nergizleme, a dish made with patile bread, boiled eggs, green onions and salt. Its name alludes to daffodil flowers (nergis). This period, which the people of Lice await with great anticipation each year, is regarded as the advent of the natural resurgence and the enhancement of fertility. The period is commemorated in the collective consciousness through the following verse:

Hivdeh û hijdehê adarê,

Milyaket hatin xwarê,

Deng kirin biharê¹

¹ “Here comes the 17th, 18th of March / Angels come down from heaven / And call out to spring”

It is also noteworthy that the food and beverage culture of Lice is particularly rich, characterised by a cuisine that showcases a multitude of local flavours. The district is home to a distinctive tomato variety, renowned for its distinctive flavour profile. The popularity of stuffed ribs (kalek) extends well beyond the boundaries of Lice.

The most significant culinary traditions of the Lice region are as follows: cheese halva (Zıvırç), made from fresh goat cheese; a type of bread baked on a stone (Nanê Kunik); a type of boortsog (Lelengi, Zingil or Pişi); bulgur pilaf with tomatoes; a type of aubergine dish (Belibağlı); a type of kebab (Meftune); and a type of pomegranate soup (Nardan Aşı or Hilolîk). Notable culinary specialities of the region include a buttermilk soup prepared with pennyroyal (Mehir), a type of dough dish that can be made both sweet and salty (Kalbur Hurması), a type of baqlava called Cendere, a type of meat stir fry prepared in copper pots and called Çepiç, as well as Kef Sucuğu, Pestil (Bastık) and Kesme.

It would be remiss not to mention the Şekerlokum cookies, sent to the groom’s house by neighbours, friends and relatives on the morning of the wedding according to a tradition known as “subhiye”. This tradition, however, has fallen into disuse in the modern era.

In these ancient lands, various ethnic groups had coexisted in peace and harmony for years, freely practising their customs and traditions. The Lice district is one of the places that has managed to maintain a unified community in times of both sorrow and joy, characterised by positive neighbourly relations. The diverse population, comprising Kurds, Turkmens, Armenians, Assyrians, Balkan migrants and Arabs, has been able to preserve their individual identities, contributing to a rich cultural tapestry.

In their daily lives and activities, women of different ethnicities were observed to engage in various social practices and customs. Old Kurdish women were seen donning kofi headdresses, also known as Zaza tassels. Similarly, women and younger females were seen wearing traditional black chadors and veils. Additionally, Armenian women could be seen adorning their distinctive headscarves and peshtamals, which are locally known by the term çit.

In this region, the role of women is significant and cannot be overlooked. In particular, the act of removing a headscarf and tossing it into the midst of a dispute is a clear indication that the conflict has reached its conclusion. In this multicultural district, women played a significant role in maintaining neighbourly relations. During the Easter celebrations, Armenian women would offer their Muslim neighbours buns and coloured eggs, while they in turn made room on their tables for their Armenian neighbours during their feasts. It is unfortunate that these harmonious interactions and traditions have been relegated to the memory of a bygone era, as they do not continue to be practised in the present.

There are many examples in this region’s history that illustrate the universal commitment to serving humanity. However, for the purposes of this discussion, I will focus on two individuals from both the past and the recent past: Saadet (Hayganuş) Hanım and Hacı Sait Şanlı. Saadet Hanım, the daughter of Ağacan, one of the most prominent Armenian merchants in Lice, dedicated herself to public service following the death of her husband at a relatively young age. This healer, attired in a black scarf and dress symbolising her mourning, would hasten to the assistance of the ailing on the back of her horse, Kolos, without distinction among her patients, regardless of gender, age, or condition, and treat them with the medicines she prepared herself.¹ Another noteworthy individual is Hacı Sait Şanlı, a peace ambassador whose reputation transcends national boundaries. He has played a pivotal role in the cessation of numerous blood feuds within the region and has been a staunch advocate for fostering peace in the region.

¹ This information was obtained from an oral history study conducted in 2012 with Nihat Işık, a member of the Lice notables and a descendant of Vakıf Ahmet Bey. He is the father of the author Süreyya Işık.

Lice is a collective memory that has been shaped by the footprints of various civilisations throughout history. Despite experiencing significant challenges in recent times, the resilience of the community has ensured its continued existence. This resilience is a testament to the strength of the collective memory, which not only represents the past but also serves as a guiding force for the future. It is incumbent upon us to ensure its continued existence into the future.

In the present era, while the remnants of Old Lice continue to exert their influence on a hilltop, bearing the scars of a bygone era, New Lice is compelled to keep pace with the demands of modernity, navigating the daily turbulence with haste. I will conclude this account of Lice with the opening stanza of the poem My Lice by my late father, Nihat Işık, who was an ardent admirer of the town of Lice.

Kevıra Kelê looks on proudly,

The Şiro Stream flows vigorously.

Mills line the stream,

My beautiful Lice breaks the heart.¹

¹ “Kevıra Kelê mağrur bakar / Şiro Suyu coşkun akar / Dere boyu değirmenler / Güzel Licem yürek yakar”

Text: Süreyya Işık

Translation: Özgür Bircan

Cover photo: Lice, Şevket Beysanoğlu Collection, DKVD Diyarbakır City Archive

BIBLIOGRAPHY

• Beysanoğlu, Ş. (1987) Anıtlar ve Kitabeleri ile Diyarbakır Tarihi, Volume 1, Diyarbakır Belediyesi Yayınları, Ankara.

• Bizbirlik, A. (1999) “16. Yüzyılın Ortalarında Atak Sancağı ve Sancak Beyleri Üzerine Notlar”, Tarih İncelemeleri Dergisi, 1: 132.

• van Bruinessen, M. (1991) Ağa, Şeyh ve Devlet [Agha, Shaikh and State], Özge Yayınları, Ankara: 356.

• Cegerxwîn (2018) Hemû Berhem, Cilt 1, Lîs Yayınevi, Diyarbakır: 111.

• Diyarbakır Provincial Yearbook, 1967: 121.

• Işık, S. (2013) “Lice İlçesi Tarihi Mekanları”, Her Yönüyle Diyarbakır İlçeleri, (ed.) Yusuf Kenan Haspolat, Uzman Matbaa, Istanbul: 93-94.

• Işık, S. (2021) “Lice Beyleri, Vakıf Ahmet Bey Camii ve Sakal-ı Şerif”, Uluslararası Ashâb-ı Kehf ve Lice Sempozyumu, Diyarbakır.

• “Liceli Hakkı Bey”, biyografya.com.

• Oral history study conducted with Nihat Işık in 2012.

• Şerefhan (1990) Şerefname: Kürt Tarihi, (translated by) Mehmet Emin Bozarslan, Hasat Yayınları, Istanbul: 278.