One can say, for various regions of Diyarbakır, that they have “hosted many cultures and civilizations”, Silvan, is perhaps the district that suits that description most.

Silvan is a district where its Babylonian, Assyrian and Persian past is kneaded first with the traces of the Roman and then the Byzantine empires, and bears the architectural and cultural riches of the post-Islam Marwanid, Ayyubid, Artuqid, Seljuk and Ottoman periods. For many years, Silvan was the capital city of the Marwanids, it was a great cultural centre of the Middle Ages and an important crossroads of the Silk Road, standing out as a significant city in each civilization in its history. It is also the stage of the Zembilfıroş Legend, and important source of Kurdish literature.

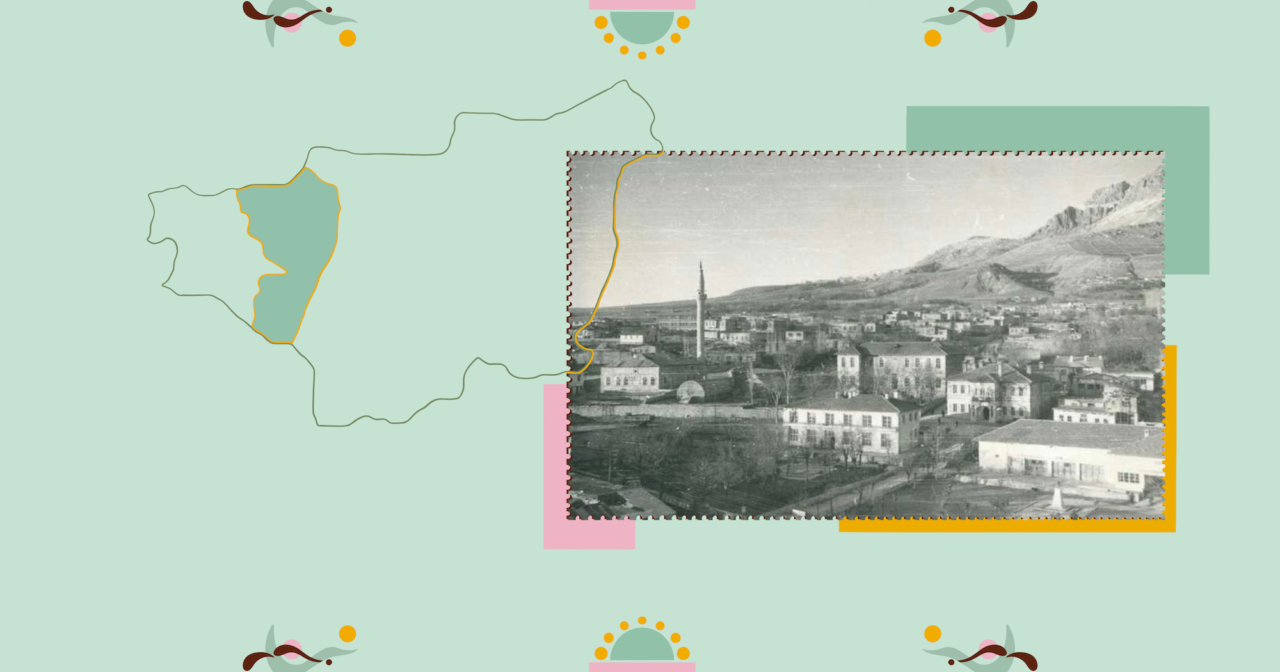

Today, Silvan is one of the most populated districts of Diyarbakır, and neighbours the city centre, and the districts of Hazro, Lice and Kulp. Dilawer Zeraq, who has carried out research on the Kurdish language, and also writes novels and short stories in Kurdish, tells us the story of his own Silvan, his Meya Farqîn¹. This is a poetic trip, where he brings together his childhood with the history of this land.

This text will refer to Silvan with its Kurdish name Meya Farqîn / Farqîn, one of the many names used for the city throughout history.

As a foundation, a fundamental building block, a source and an element of culture and history, Meya Farqîn is a sign of existence founded to the east of Diyarbakır. And it is such a city that it has shouldered its history and brought it to the present day.

The Farqîn I speak of in this text, beside being a site and city of existence, also holds a significant part in my personal history and experience.

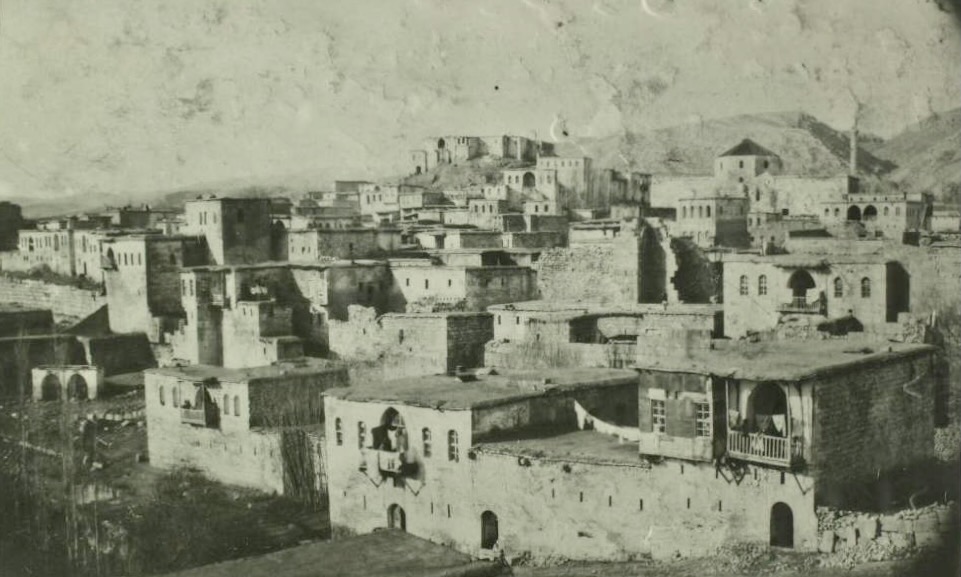

As a physical and geographical site, Farqîn leans, to the north, on the Albat Mountains (Çiyayên Elbatê) and was founded on a piece of land surrounded on three sides by city walls. The city walls that surround Farqîn have been constructed with cast mortar, and are unparalleled in history. There are remains of some of the gates along the city walls, however, only the Kulfa Gate (Deriyê Qulfayê or the Eastern Gate) stands in its authentic historical form.

When you cross the borders of Farqîn via the old road on the Diyarbakır side, you reach the Agricultural Gardens (Baxçeyên Ziraetê), which, according to oral history accounts, were full of all kinds of flowers and fruit trees. Heading towards the centre of Farqîn from there, you climb a slope via a steep ridge, where you are met with a miniature Keçi Burcu, the Bastion of the Goat (Birca Keçikan).

This bastion is a magnificent symbol of Farqîn. Besides, for me too, it is a place that enabled me to notice, and what’s more, be dazzled by unparalleled beauty. That source of infantile amazement is not erased from your memory even when you grow up.

I was a child; I was about seven or eight years old. We, all the neighbours and the family of my paternal uncle, had taken a trip to the Agricultural Gardens to celebrate Serê Gulanê.¹ We had entered the grove through the Garden Gate (Deriyê Baxçê). On the way back, my mother and her friends had walked towards the Main Gate to head home, and we were walking uphill in front of the hospital. When my aunt-in-law, pointed with her hand and said, “They have written something on the bastion of the district governor’s house”, I interrupted my joy of being at a picnic and turned my head where my aunt-in-law was pointing. Yes, there was some writing on the angular wall. But what did the ‘district governor’s house’ mean? What or who was the district governor? I had no idea. Then, when I asked “What is the district governor?”, the answer I received was “a statesman”. A long time later, when I had grown up and matured, I would realize that the ‘district governor’s house’ was a physical entity constructed on the cast mortar bastion’s land, as if to encroach into Farqîn’s historical memory.

¹ The Arrival of Spring, 14 May.

The Arrival of Spring / Serê Gulanê

The coming of spring, the awakening of nature has been celebrated throughout history in most societies with holidays and festivals. The Arrival of Spring (Serê Gulanê) is a traditional spring festival of Silvan. Although it is unclear when it was first celebrated and by whom, there is a claim that it originated in the period of Marwanids. Another viewpoint, although not indicating any specific date, argues that it began to be celebrated when spring came following a great period of drought.

If we travel further into past, we see that the organization of festivals for rain, abundance, plentifulness and a harvest period without famine and illnesses goes back to antiquity. The Hıdırellez celebrations, held on 6 May, believed to have first begun in Mesopotamia and Anatolia, share the same root. Serê Gulanê is a tradition continued by the peoples of Silvan.

The holiday, held on 14 May according to the Gregorian Calendar, is celebrated at picnic sites, river springs and source waters, with festivities continuing throughout the day. For this special day, which brings together families, neighbours and all the peoples of Silvan whether they know each other or not, preparations of food begin much earlier, and musical performances and events are sometimes added to the picnic.

Source: Fatma Durma, “Bayramları, İnançları ve Efsaneleriyle Silvan [Silvan, with its Holidays, Beliefs and Legends]”, in Sultanlar Şehri Silvan: Eğitim-Kültür- Medeniyet [Silvan, City of Sultans: Education-Culture-Civilization], Sonçağ Akademi Yayınları, 2021, p. 305-313.

When Farqîn was Meya Farqîn, it became a hub of urbanization and civilization, and to understand its extent better, one must look to the Ali Agha Townhouse (Mala Elî Axa) and the Sevdîn Pasha Mansion (Koçka Sevdîn Paşa). Both buildings, along with adjacent structures, stand out with their beauty, unique symbols of a period and sovereignty.

The first time I met such grandeur was at the Sevdîn Pasha Mansion. Special craftsmanship, mastery and labour were displayed in the construction of the mansion, and it had also become one of the authentic signs of sovereignty in its time. The building later served the people of Farqîn as the Gazi Primary School. The first day I started studying there, I felt the odour that had accumulated in the memory of its whitened stones. That odour enveloped my heart for many years, I craved for it. ‘Did you never forget it?’, I hear you ask. No, it was impossible to destroy that odour of the stones with an artificial reading of history. That odour I can still smell was a reflection of the civilization and existence that embroidered the stones that it pervaded with its patterns and engravings.

Not only Ali Agha Townhouse and Sevdîn Pasha Mansion; when you look towards Taxa Kurmancan (Kale Neighbourhood), you will notice Mîrler Castle (Kela Mala Mîran), built on a rise resembling a mountain. From high, it takes a deep look at Farqin, and appears to say, in majestic tone, “My sovereignty has always been, since the time of the Marwanids, about seeing, experiencing, realizing, about knowledge and tolerance”. When you walk from one end of Taxa Kurmancan to the other, turning slightly downwards on the right, you see the Selahaddin Eyyubî Mosque (Camîya Ecem). The architectural magnificence of the mosque, the stone engravings and patterns bring the Roman period and the labour of the Marwanids to the present day. You inadvertently ask yourself, “I wonder how many buildings changed form in the memory of Meya Farqîn, and how did the historical memory of the city conceal itself in the colours and odour of the stones that made up these buildings?”

After the dazzling grandeur of the Selahaddin Eyyubî Mosque, when you turn towards Derîyê Deştê (Ova Kapısı, The Plane Gate), it is the Üstünler Townhouse (Mala Evdila Beg), resembling the palaces of the state and sovereignty rather than a townhouse, that greets you. And in this way, one understands that Meya Farqîn is not merely a city, but a site of existence and that it was built as a “city-state” with millennia of civilizational history.

I remember it from the picnics we went to on Serê Gulanê and on spring days. When you turn northeast from the Üstünler Townhouse, or the administrative palace, you came across the Great Fountain (Kanîya Mezin), the Middle Fountain (Kanîya Navîn) and vineyards and orchards quenched with the cold and luminous waters of Şador. Here, the trees that both gave fruit, and were used for wood to build houses, extended from the Üstünler Townhouse to Zembilfiroş Castle, and with their unique odours, lend further colour to Meya Farqîn.

Nature is part of Meya Farqîn’s memory, and is also the reason it is called Green Silvan (Farqîna Rengîn), however, today nature has been displaced by concrete buildings, and the smell of nature has long gone. In this distorted and deformed state, Meya Farqîn sends my personal memory into disarray, casting each piece of it into a blind well where the memory of history and civilization rots.

One day, returning from a picnic and a tour of vineyards and orchards, I realized that Zembilfıroş Castle and the cool waters and fertility of Şador, turned the radiance of Hatun into a pale and thirsty love for the basket-maker boy of Farqîn.¹

When you enter through the walls of Zembilfıroş Castle from the north, or from the side of the Albat Mountains and Şador, you see how brilliant the civilization founded by Mir and Hatun was. The Zembilfıroş Bastion, in all its splendor, and also, with pride of its sovereignty, turns its face to the East, and seeks to claim dawn as its own, as if to compete with the break of day.

Kulfa Gate, one of the nine gates of Meya Farqîn, is the only gate that has retained its authentic architectural form. With its guards that never sleep, it protects Meya Farqîn, so the love of Hatun and Zembilfıroş never fades or lose its taste, and they benefit from the golden rays of the sun.

¹ One of the riches of Kurdish literature, the Zembilfıroş Legend tells the story of the son of a beg, who renounced his father’s fortune and the fruits of the earth to make a living for his family by making baskets, and Hatun, who fell in love with him. Hatun was the wife of a mir [rural Kurdish chief], and her love remained unrequited.

Exiting from the Kulfa Gate, if you travel by car for about 10-15 kilometres towards the East, you can visit the Hassuni Caves (Şikeftên Hesûnê) so you can observe how once people led lives of great difficulty. Later, if you still have the strength to climb higher, you should also look inside the cave, so you can see their rituals of bidding farewell to the dead, their living rooms, work areas and their skills of hunting. And of course, before descending back from the Hassuni Caves, you must turn left to enjoy the view of the Batman River (Çemê Bazmanê) and Malabadi Bridge (Pira Mala Badê).

In my childhood, my father used to go swimming to the Malabadi Bridge every Sunday during summer. The first time he took me there, upon seeing the Malabadi Bridge for the first time, I asked in amazement, “How come these huge stones are stuck together and don’t fall apart?”

Of course, the stones constructed as a bridge of passage by Bad, the son of Marwanid’s friend would be as majestic as the sovereignty of the Marwanids, and be recognized as one of the widest and largest examples of single-vault bridges.

After this trip outside the city, if we return to Meya Farqîn, turn left from the Kulfa Gate, and look towards the West from beneath the city walls, you see the view of the Azizoğlu Townhouse (Mala Azîzan), adorning the Plain of Farqîn. Turning around at the road below, before coming to Altıbulak Fountain (Kanîya Dergeh) – where one finds one of the remaining gates – one must observe Azizoğlu Square, where Kırık Minare (Minara Qot), the Broken Minaret is, a site which still bears the odour of the Romans and Marwanids. This site is a significant part of Farqîn’s historical heritage.

According to oral history, Farqîn has been demolished seven times, and rebuilt every time. During every demolition, a piece fell of the minaret. With its remaining parts, when darkness descends, Kırık Minare acts as a night-watcher during Farqîn’s fierce nights, and in the daytime, reflects its splendour across Farqîn with its engravings and patterns.

After enjoying the happiness of looking at the stonemasonry and millennia-old grandeur of Kırık Minare, you can turn your face back toward the city, rest a little at the Altıbulak Fountain, and observe the unique beauty of the high city walls built with cast mortar. Then you can walk uphill from the Altıbulak Fountain Gate, to reach the Silvan Market Square, where all manners of crafts and skills are exhibited, home to caravans and once a hub of regional trade.

Once you go past Şeytan Pazarı, or the Devil’s Market, progressing along the street towards the left, you come to the Armenian Church (Dêra Ermenan). Although I say this is an Armenian Church, do not take my word for it. What I want to talk about has both to do with the city’s historical memory, and my own personal memory.

I have a strong memory, I was eight years old when, having extended my head out of the broad window on the second floor of our home with a courtyard, a staircase and tall columns, I saw a building to my left. Probably thinking I would be curious about it, my mother answered before I asked, “That’s a movie house, son. It used to be Halkevi, the People’s House. And long before that, it was a church”.

You will guess, of course, that I asked her before she had completed her words:

“What is a church, mother?”

“It’s a monastery, my son.”

“So what’s a monastery, dear mother?”

“It’s the place where Christians pray to God.”

This church, used as a mosque today, melted my conversation with my mother, my religious memory and the religious and historical memory of Meya Farqîn in the same pot, earning its place both in my personal memory and in the memory of the city.

Once you complete your tour of Meya Farqîn and head towards Diyarbakır, a number of questions appear in your head, while the city folk, who possess an awareness of their existence and past, keep your memory alive with their dynamism and communication. And they always seem to say:

“Welcome to our city which lives time in its soul. Meya Farqîn is the city of existence. You are welcome to come again!”

Text: Dr. Dilawer Zeraq

Translation: Nazım Dikbaş

Cover photograph: Malabadi Bridge, Orhan Kartal, 2015, DKVD Diyarbakır City Archive