Ulu Cami, or the Grand Mosque, is located in one of the most crowded areas of Diyarbakır, and its rhythm and depth pulls us into its universe the moment we enter the courtyard. The unique and rich atmosphere of this impressive building derives from the fact that it has taken shape as history has flowed. Every architectural touch, every new addition bears political and religious traces of different civilisations, beginning in the 7th century. Still a temple, Ulu Cami also stands as a monument of the cultural, linguistic and religious diversity of the city.

Ulu Cami, a symbolic building of Diyarbakır, is in the Cami-i Kebir Neighbourhood, in the north-western section of the traditional urban area surrounded by the city walls. Various sources state that the structure was transformed from the Mar Toma Church upon the entry of Islam into the city in the year 639. The plan and dimensions of Mar Toma Church are not known today. After the city passed into the rule of the Seljuks in 1085, the building underwent comprehensive repair in 1090. The many inscriptions on the building show that in the following periods, it was restored by many different civilisations, and that additions were made. The square-body minaret was constructed in 1839, while the fountain in the courtyard was added in 1849.

Associate Professor Meral Halifeoğlu, Restoration architect

Ulu Cami is built on a site which could be considered the religious, cultural, commercial and political centre of urban life. With additions, expansions and repairs carried out during different periods, the building became the monumental complex we see today. Although there is no certain source to indicate when it was constructed, material data from buildings that form the complex, structure types, building techniques and ornamentation elements all show that the building was among the most significant religious and cultural centres during Diyarbakır’s formation process.

Associate Professor Birgül Açıkyıldız, Art historian

In addition to being a holy site where throughout history, communities that have lived and continue to live in Diyarbakır have practiced their religious rituals, Ulu Cami is also a place of social activity. Since it has been the most significant, monumental symbol of all political powers that have ruled over the city, and contains traces of all communities that have lived here, it bears great political symbolism. In this sense, Ulu Cami provides important data in terms of cultural and religious interaction, as a reflection of the multi-ethnic, multi-linguistic, multicultural and multi-religious structure of the city.

Birgül Açıkyıldız

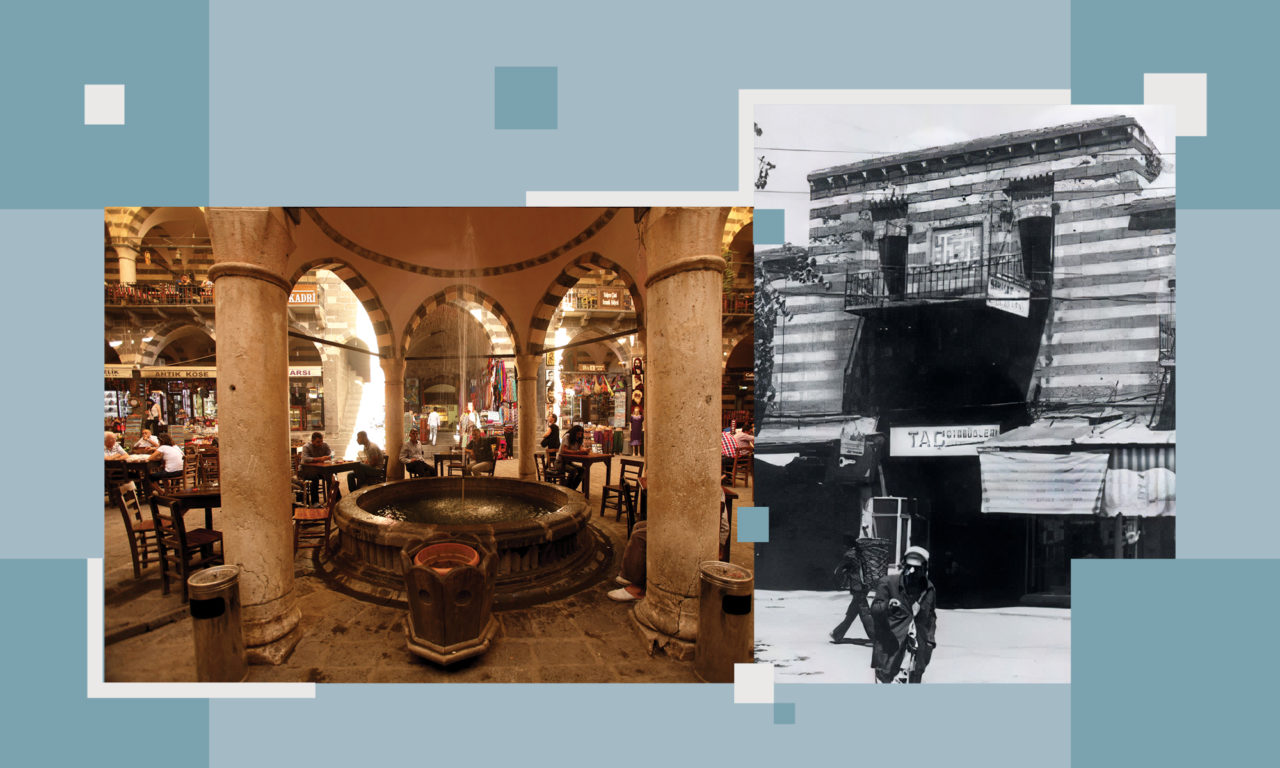

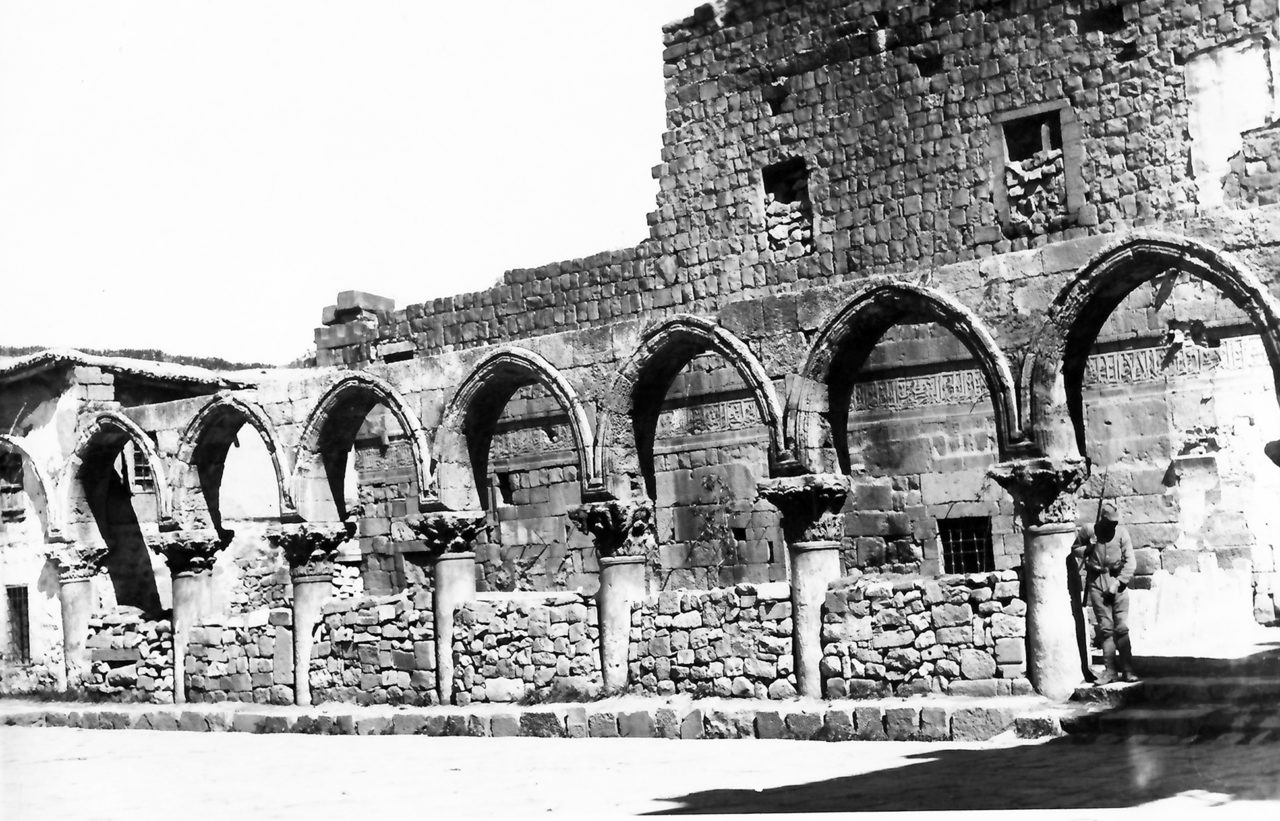

The vaulted main entrance on the east wing of Ulu Cami cannot be fully perceived from the outside because of the higher elevation of the market place right in front of it. The other entrances open onto traditional streets. The courtyard wings of the mosque are made mostly from basalt, and are enriched with columns and ornamentation of various forms, deemed to be spolia.

Meral Halifeoğlu

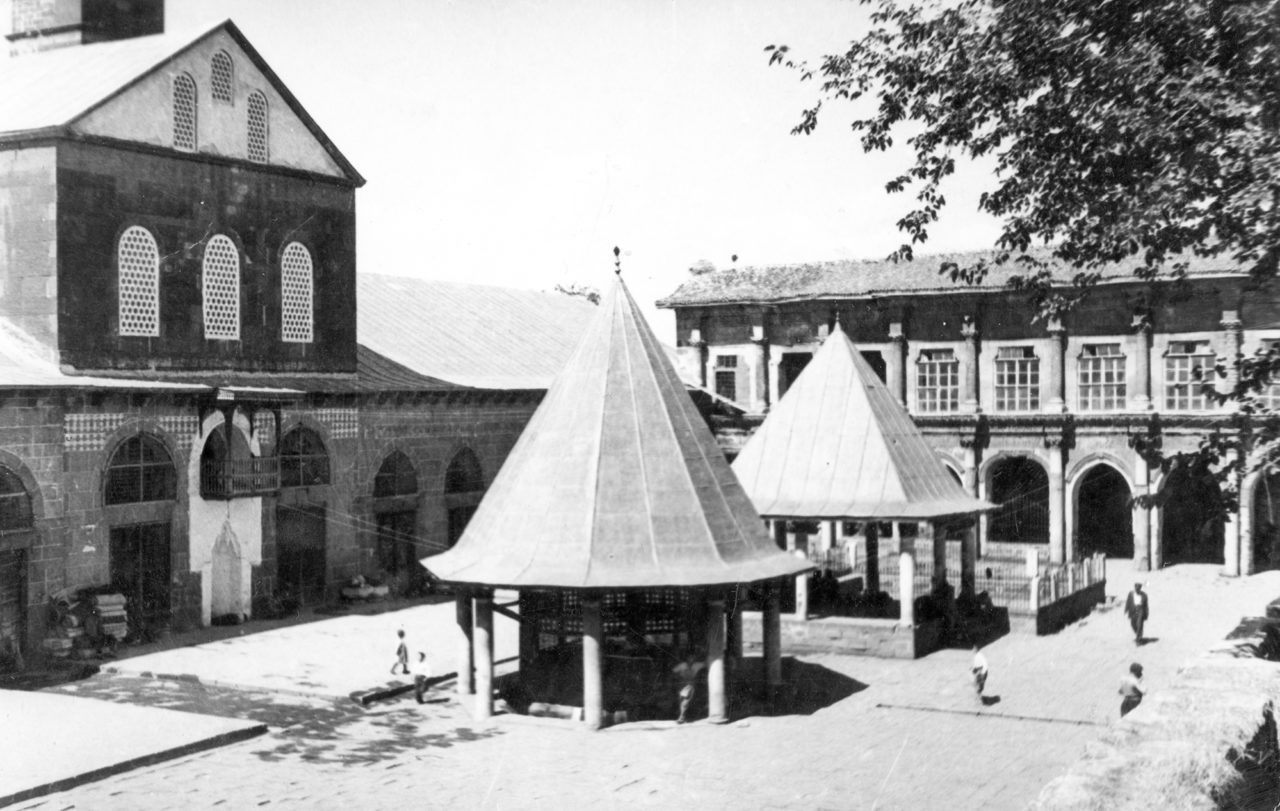

The wide courtyard of the building forms a near-rectangle: To the south of it, there is the Hanafi Section; to the north, the Shafi’i Section, the northern entrance, the Mesudiye Madrasa, the south portico, a traditional house and public toilets; to the east, the library, which is said to have once been a muvakkithane, or timekeeper’s office, and the eastern entrance; and to the west, the west portico including the western entrance, and above, the Koran course classrooms. Other structures in the wide courtyard include the octagonal, pointed, cone-shaped fountain, built during the Ottoman period, a namazgâh, or prayer area, elevated by a few steps, and a pool. In the north of the courtyard there is the Mesudiye Madrasa, the courtyard portico, and in front of the northern entrance, a sundial.

Meral Halifeoğlu

Archaeological sounding carried out from 2010 to 2017 at different parts of the complex reveals the existence of a great diversity of cultural layers both side by side, and on top of each other. It has been shown that the structure has served as a cult centre in uninterrupted fashion at least since the Roman period (4th century AD). The building contains archaeological findings that belong to a forum and cathedral from the Roman period. Many columns or sill plates taken from the ancient theatre and used as spolia also shed light on the strong Hellenistic-Roman period of the structure.

According to historian Al-Waqidi (d.823), the Diyarbakır Cathedral was used jointly with Christians after the city was conquered by Arab forces in the 7th century. Two thirds of the structure was converted into a mosque while one third was reserved for the Christian community.

Birgül Açıkyıldız

The bas-relief figurative motifs symbolizing the struggle between good and evil on the eastern entry façade of the structure quite possibly refer to its Zoroastrian past. When in the year 639, during the reign of Caliph Omar, Sasanian rule was ended and Diyarbakır was added to the Islamic Empire, Zoroastrianism was the official religion of the Sasanian Empire and the faith of the vast majority of the people in the region.

Birgül Açıkyıldız

The Hanafi section in the south wing of the courtyard has a transversal arch plan; the ceiling also features wood girders and a hipped roof. The Shafi’i section and the Eastern and Western Maksuras also feature ceilings with wood girders. This traditional Diyarbakır construction technique is not only practiced at the Mesudiye Madrasa and the public toilets. The ceiling of both buildings feature vaulted brick masonry roofs and cloisters surrounding the courtyard. Limestone has been used in the arched vaults of the Mesudiye Madrasa and the Western Maksura, some of the complimentary wall masonry in interior spaces and the ornamentations and inscriptions on façade surfaces. Among the materials used in the courtyard façade of the Eastern Maksura there is basalt and limestone, and also marble and breccia.

Meral Halifeoğlu

The earliest inscription from the Islamic period dates to 1091. Since the building descriptions of Persian traveller Nasir Khusraw, who visited Diyarbakır in 1046, largely overlap with current building features, 1091 should be considered not a construction but a repair date.

The Hanafi Masjid to the south of the courtyard is probably the oldest structure of the building complex. In terms of a section of the current church being previously used by Arab Muslims jointly with the Christian community, there is a genuine similarity with the Damascus Umayyad Mosque (706-715). Therefore, it is possible to claim that this section was built in the early 8th century.

The Mesudiye Madrasa, the Shafi’i Mesjid, the structure to the north of the Shafi’i Mesjid, known today as the public toilets and probably once used as a madrasa, the Zinciriye Madrasa to the west of the Hanafi Masjid were all added at different periods of Islamic rule to extend the complex.

Birgül Açıkyıldız

Touring Ulu Cami, we come across a historical record about the Hevsel Gardens. The fact that Diyarbakır, or Amid, the name it carried then, is mentioned along with the Hevsel Gardens even in the oldest accessible records, seems to indicate that it always co-existed with the gardens. The inscription on the western side of the main entrance of the mosque’s Hanafi Section brings a record from the Middle Ages, from the year 1241 to the present day.

The inscription mentions Sultan Gıyaseddin’s abolition of taxes levied from Hevsel (Evsel), Mardinkapı, Urfakapı and Diclekapı, and this practice that encourages production is praised. The full translation is as follows:

“I begin with the name of Allah. Thank Allah who has alleviated our sorrow. The Supreme Commander Grand Sultan Gıyaseddin (May Allah render his sultanate long-lasting) has ordered the abolition of taxes from Evsel, Mardinkapı, Urfakapı and Diclekapı. He carried out this as a permanent act of charity for the benefit of the people of Amid. Whoever may change this order although they have knowledge of it will face the consequences. No doubt Allah hears and knows all. May Allah accept all beautiful prayers said for the continuity of the state of the sultan as long as the earth and sky remain. This work was done in the year 639 (1241). May the name of the Prophet Muhammad be praised.”

Gümüş, E. (2015) “Hevsel Bahçeleri’nin Tarihi Süreçte Amid/Diyarbekir Şehri İçin Taşıdığı Önem ve Bu Hususun Vesikalara Yansımaları”, Diyarbakır Kalesi ve Hevsel Bahçeleri Kültürel Peyzajı, (ed.) Nevin Soyukaya, Diyarbakır Büyükşehir Belediyesi Diyarbakır Kalesi ve Hevsel Bahçeleri Kültürel Peyzajı Alan Yönetimi Başkanlığı Yayınları, Istanbul: 153.

Although it had been subjected to interventions during different periods, interventions not in harmony with the essence of the Ulu Cami building complex were removed during the comprehensive restoration implemented from 2010 to 2017. Work carried out by the Foundations Regional Directorate removed recently-added concrete covering, ceiling, flooring and other low-quality additional elements. Original stone surfaces that had been plastered with concrete-based materials were cleaned. Research excavation revealed information about the previous periods of the structure, accessing information about different periods especially in excavation carried out in the east and south sections of the interior and exterior of the Hanafi Section. Excavation areas were taken under protection with walking paths, acclimatization and roofing. Ulu Cami is open both for prayer and visits today.

Meral Halifeoğlu

(Photograph: Dilan Bozyel)

Ulu Cami has a direct, organic relationship with the city’s life, it is not an isolated structure, or an unapproachable religious space. The eastern gate, designed as the main entrance, opens onto a wide external courtyard where women and men, young and old, people from all religions and nations sit and chat, sipping their tea. The mosque is in the city centre, but bordered off with high walls from the city noise, and presents a highly spiritual atmosphere, yet it is also easily accessible and an important pass-by in their everyday lives. And that is why it is the heart of the city’s memory.

Birgül Açıkyıldız

Translation: Nazım Dikbaş

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Birgül Açıkyıldız

• Akok, M. (1969) “Diyarbakır Ulucami Mimari Manzumesi”, Vakıflar Dergisi, 8: 113-139.

• Gabriel, A. (1940) Voyages Archéologiques dans la Turquie Orientale, Paris: 197-199.

• Halifeoğlu, M. and Assenat, M. (to be published) Evaluation of the Excavations Carried Out Between 2010 and 2017 in Diyarbakır Grand Mosque Community Building for Restoration Work: Hanafis Section and Eastern Maksurah.

• van Berchem, M. (1910) Amida: Matériaux pour l’Epigraphie et l’Histoire Musulmanes du Diyar-Bekr, Carl Winter’s Universitätsbuchhandlung, Heidelberg: 51.

• Sözen, M. (1971) Diyarbakır’da Türk Mimarisi, Istanbul.

• Top, M. (2011) “Diyarbakır Ulu Camii ve Müştemilatı”, Medeniyetler Mirası Diyarbakır Mimarisi, (ed.) İrfan Yıldız, Diyarbakır Valiliği Kültür ve Sanat Yayınları, Diyarbakır: 185-226.

• Tuncer, O. C. (2015) Diyarbakır Camileri. Diyarbakır.

Meral Halifeoğlu

• Tuncer, O. C. (1996) Diyarbakır Camileri. Diyarbakır.

• Archive of the Diyarbakır Foundations Regional Directorate, 2014.