Hazro is a small district of Diyarbakır with a rich history and a wealth of geographical riches that point to the ancient periods of human history, as is the case with many other places in the region. Prior to its designation as a district in 1954, it was a township within the Silvan district.

For author Muharrem Erbey, Hazro represents a duality: on the one hand, it is the physical location imbued with the tangible memories of his childhood, and on the other, it is an intangible source shaped by the collective narratives he encountered through his grandmother Hezê, the regional folklore, and the oral traditions that persist in the region. In his account of Hazro, Erbey not only provides an introduction to the district for those who are unfamiliar with it, but also illustrates the impact of its geography on his writing and identity.

The following account attempts to provide an overview of the historical Hazro, the setting of the Kurdish fairy tales of my grandmother Hezê, which played an instrumental role in my early literary development. It is situated amidst a landscape of dramatic topography, offering a sense of tranquility and respite.

The most profound and enduring impressions of Hazro that remain with me are the Kurdish songs performed by my grandfather Hacı Salih, who was a dengbêj, with his left hand to his ear; the mystical narratives known as hebroşk in Kurdish, which my grandmother Hezê recounted by the light of kindling; and the imposing mountains that seem to call out from afar.

During my childhood, the route from Diyarbakır city centre to Hazro by bus entailed taking the left-hand road after Başnik at the Siirt road junction, which led to a flat plain. Upon traversing the villages of Dersil and Mêrenî and nearing the precipice between the mountains, one would espy the “Bride and Groom Boulders” situated on the left side at the summit of the mountain. These boulders, according to local legend, represent a wedding procession that was abruptly transformed into stone due to their untimely passage. As we gazed at the boulders with reverence, we proceeded to traverse the Zuğur Gorge, which serves as a gateway to a realm of myth and enchantment.

Zuğur Stream, the most significant water source in Hazro, where the continental climate is predominant, originates in Zergüş and subsequently joins the Tigris River in Bismil, ultimately flowing to Basra.

Upon entering the Zuğur Gorge, our attention was immediately drawn to the green poplars, oak, and juniper trees rustling in the wind above the Zuğur Stream. Akin to the gradual unfolding of a film frame, the scene was further defined by the presence of mudbrick village houses built on the ridge of the mountain, the massive bare rocks, and the mountain village with animal pens.

As we proceeded towards the renowned stone mills situated along the Zuğur Stream, we would observe the impressive Biler Mountain (Zinarê Biler) on our right and the imposing Horoz Mountain (Zinarê Dîk) on our left. As we proceeded towards Hazro, which was constructed on a hilly terrain at the southern base of Mount Uzuncaeski (also known as Khaçerdum/Hacertum in Armenian and Girê Habo in Kurdish), we were compelled to observe with a sense of unease the ruins of Tercil Castle situated on the mountain’s summit to the left.

Upon arrival in Hazro, we would navigate the labyrinthine streets, paved with aged stones, that constituted the marketplace. We would then proceed to traverse the expansive properties of Hazro beys, before finally reaching my grandfather Hacı Salih’s two-storey stone residence, situated in the Bahçe neighbourhood.

The same cobbled street led to the square in front of the Mosque of Bahçe neighbourhood, where we used to play at a spot called sere sergo, which can be translated as ‘garbage dumping place’. I would traverse the neighbourhood, which was characterised by red stones and known as Kevirê Henît (red stone), and proceed to the Kaniya Mesîlkê (Mesîlk Fountain). This was a locale frequented by women from Hazro, who would engage in the washing of clothes and bathing activities during the daytime. It was also purported that jinns and fairies would visit at night for similar purposes. I would then proceed to the district cemetery, which I recall evoking feelings of trepidation, and finally, the football field, situated in proximity to the source of the Zergüş Stream in Aunt Gulo’s gardens. It was here that I would plunge myself into the icy water.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Armenians engaged in various crafts, including weaving, trade, and viticulture, lived alongside Kurds in the region of Hazro. The artisans, particularly the weavers, of Agrak, Bashneg, Dersil, Hodnov, Cirnokh, Silleman and Kufercin, the largest of the thirty villages in Hazro where the Armenian population was dispersed at the beginning of the 1900s, were justly renowned for their skill and craftsmanship.

The region of Hazro was previously supplied with coal for fuel from anthracite quarries in the area, which were operational until recently. Currently, agricultural activities, including farming in the plains, viticulture in the mountainous region, and animal husbandry, as well as small-scale commercial enterprises and carpet weaving, are conducted in the district centre. Wheat, barley, chickpea, lentil, tobacco and cotton are cultivated in the region. Additionally, the region boasts a plethora of mineral deposits, including oil, pink marble, lignite, iron, and sulphur.

Since 1988, a substantial number of trainees have been engaged in the production of Hereke carpets on 66 looms established in Hazro with the support of Sümerbank. This initiative was undertaken with the objective of reviving the carpet weaving trade, which had been previously practised by Armenians in the region. The production in the two workshops has consistently ranked first among Diyarbakır districts in terms of productivity and quality for years, and the carpets woven are also exported abroad.

The architectural style prevalent in Hazro is characterised by two-storey masonry houses. The roofs are typically constructed from earthen materials, with the first floor serving multiple purposes, including as a corral, toilet, bathroom, and cellar. The second floor is designated as the living area. The walls of the houses are constructed from yellow stones (limestone) that are native to the region, while the ceilings are comprised of wooden logs.

In the living rooms of the houses, there were small fireplaces that were consistently maintained and referred to as kuçik. During both summer and winter, we would gather around these fireplaces to engage in nighttime conversations known as şevberk, and partake in a variety of traditional foods, including pestil, sausages, dried figs, and raisins. Flour from the mill was used to prepare baked goods, which were cooked in the tandoor.

In the present day, a number of two-storey stone houses in a few neighbourhoods in the historic district of Old Hazro, along with several large mansions that were once the residences of Hazro beys, are awaiting restoration. These properties that were visited on two occasions by Atatürk, who stayed for several days on each occasion are currently in a state of disrepair and neglect.

In the past, there were approximately ten well-known stone mills, known as aş in Kurdish, situated on the banks of the Zergüş Stream. Those who arrived in Hazro with their donkeys from the neighbouring villages and districts would leave their loads at the mill and repose beneath the trees.

In those years, donkeys were costly and highly prized for their utility in both riding and transportation. As time passed and the donkeys belonging to those who frequented the mills began to disappear, the term ‘Kerdiz’, a combination of the Kurdish words ‘ker’, meaning ‘donkey’, and ‘diz’, meaning ‘thief’, came to be used as a nickname for the people of Hazro. Still today, when I state that I am from Hazro during introductions, the other individual may respond with a wry smile and say “Ha tu jî kerdiz î,” which translates to “So you are a donkey thief too” to which I respond with a smile and a nod.

The settlement was known as Hataro during the Assyrian period. Subsequently, it was referred to as Hacra, Hızro, Khazru and Hazrav. The name of Hazrav, as a town situated 72 kilometres northeast of Dikranagerd (Amid) in Western Armenia and characterised by its vineyards and numerous ice-cold springs, is mentioned in the religious edict of the Saint Hovhannes Yeghirdut Monastery in the Taron region, dated 1445. Given that the Armenian alphabet transcribes the ‘o’ sound as ‘av’, the name Hazrav is pronounced as Hazro.

The earliest evidence of human habitation in Hazro dates back to the prehistoric era. The room-shaped caves carved into the rocks on Mount Biler in the south of the district can be considered the nuclei of the settlement from this period.

The ruins of Tercil, Ayn Dar and Mihrani castles in Hazro have survived to the present day. Situated on a high hill to the west of Hazro, Tercil Castle, originally designated Hataro and subsequently referred to as such, is believed to have been constructed during the Assyrian era. Tercil Castle has been under the dominion of a succession of empires since ancient times including the Persian, Macedonian Kingdom, Seleucid, Roman, Byzantine, Seljuk and Ottoman empires.

Upon the incorporation of Diyarbakır and its environs into the Ottoman Empire in 1515, Hazro constituted one of the 24 sanjaks comprising this province. In the present day, Hazro is comprised of seven neighbourhoods, 24 villages and 37 hamlets.

When we speak of the beys of Hazro we refer collectively to members of the Tercil lineage. Tercil (Tırcıli) constituted one of the principalities descending from the Kurdish Zirkan tribe. The Kurdish rule in the region commenced in the 16th century and persisted until the 19th century.

The Zirkanids are also mentioned in Sharafname, which is an important source of information regarding Kurdish history:

“The origin of the Zirkanids is, in fact, Tercil and Atak.¹ (…) Seyyid Hasan (…) a descendant of the first Zirkan ruler, arrived from the country of Damascus in the province of Mardin, where he settled in the Atak district and devoted himself to worship, piety and austerity (…) According to one account, he was referred to as ‘Sheikh Hasan-i Ezrakî,’² due to his blue eyes, while another suggests that he was known by this name due to his consistent wear of blue attire. This was during the period when Amîr Artuk bin Ekseb, one of the most prominent military leaders of the Seljuk Empire, exercised authority over Amed, Mardin, Harbut, Mıcıngerd and Hasankeyf on behalf of the Seljuk Sultan.

According to one story, this bey had a daughter who was both beautiful and highly intelligent. The girl was beset by an intense infatuation that bordered on madness. Even the most highly trained physicians and skilled healers were unable to provide an effective treatment for her condition. The situation was becoming increasingly dire on a daily basis. Given the circumstances, Emir Artuk was compelled to solicit the assistance of Sheikh Hasan al-Azraqi, who was asked to intercede with Allah for the girl’s recovery. The Sheikh commenced the invocation with the recital of certain supplications, after which he proceeded to pour the contents of the vessel containing the water upon the head of the ailing girl. With the assistance of the pious Sheikh, Allah Almighty bestowed healing upon the girl. The Amir then sought to wed his daughter to the Sheikh. When the latter declined, the Amir instead married her to the Sheikh’s son, Hasan, and subsequently bestowed upon him the rulership of the Tercil district.”

In his travelogue, Evliya Çelebi also makes reference to Tercil Castle, citing an instance in which an Ottoman vizier ordered the repair of Van Castle and dispatched a captain with Sultan’s orders to oversee the repairs.

¹ Tercil is a castle located in Hazro, while Atak is a castle situated in Lice.

² Ezrak (‘azraq): Sky coloured, blue in Arabic.

During my childhood, I experienced a couple of episodes of syncope. To get to the bottom of this phenomenon, my mother, Fatma, and my grandmother, Hezê, accompanied me on a visit to Tercil Castle. We climbed up the steep mountain terrain on donkeys and gained access to the ruined monastery inside the castle. My mother had told me that a wise old man would speak to me in my dreams and show me the way to healing if I slept on the cushion she had placed on the floor. On that warm summer’s day, I tried to fall asleep in the bright monastery ruins, which were open on all sides. But I didn’t succeed and we returned home.

The Ulu Cami (Great Mosque), constructed on a hilltop, has undergone significant alterations over time, resulting in the loss of many of its original architectural elements. My grandfather, Hacı Salih, would make his way to this mosque with his rifle in tow at the appointed hour for iftar during Ramadan. There, he would announce the time for the breaking of the fast by firing his rifle into the air.

The absence of an inscription precludes an exact determination of the date and builder of Ulu Cami. Some sources posit that the mosque was constructed during the 13th century, during the Ayyubid period, while others suggest that it was erected in the 16th or 17th centuries, given its resemblance to Ottoman architectural styles.

The mosque is rectangular in plan and constructed from cut stone. The entrance door and mihrab niche feature intricate muqarnas and geometric decorations, while the two-storey façade is characterised by authentic masonry.

Prior to 1915, the centre of Hazro was home to two Armenian churches and an Armenian school with around 50 students. The Surp Shimavon Church was constructed in 1851, while the Surp Asdvadzadzin Church was erected in 1849. None of the aforementioned edifices have survived. At the turn of the 20th century, approximately 400 Armenian households were resident in 30 villages in this region, along with their religious and cultural buildings including the Monastery of Sourp Tovmas, which was built in 1704 in the village of Yerhisar (Tercil) and the Surp Asdvadzadzin Church, constructed in 1853 in the village of Çökeksu (Ayn Berik, Aynaprig, Ayndav). During the Armenian pogroms of 1895-96, Hazro and the surrounding villages were plundered. In 1915, the Armenian population was completely exterminated in Newala Xaço (Mekaba Xaço) and Şikefta Dibûrî, which are situated in close proximity to Hazro.

Only a small number of surviving remains of Mêrenî Castle attest to its former existence. It is believed that the tomb of Sheikh Hasane Zeraki is located in the village of Ülgen (Mêrenî). It is a long-standing belief that patients suffering from paralysis who visit this site on three Thursdays will be cured. In accordance with the prevailing tradition, it is believed that the patient will recover when one of the sheikh’s descendants touches the patient’s back with a Shimik (sacred slipper) or with their hand. In addition to the Mêrenî shrine, the shrines of Shahabuddin and Shapur, Sheikh Zeydin and Sheikh Fahri also attract considerable numbers of visitors.

The Şikefta Qeblê (Keble Cave) is situated at the foot of Tercil Castle, in close proximity to the centre of Hazro. It is of considerable size, and is said to be so expansive that it could conceivably encompass the entirety of Hazro. Newala Kûrê (Kure Plain), situated below Çökeksu, one of the central districts of Hazro, is a gently sloping plain characterised by abundant greenery and cereal crops. Both places are still the subject of stories about the massacre of Armenians in 1915.

Ayn Dar Castle was constructed on a rocky promontory overlooking the plain, with a strategic view of the road that traverses the region from the ancient city of Amid to Erzurum via Genç, which used to be called Daraheni, Çevlik and Bingöl. The castle, which contains cisterns, monumental rock tombs and secret tunnels, is dated to 3000 BC. Discovered to contain pottery with Assyrian and Akkadian traces, the castle was designated as ‘Historical Kela Rock Tombs’ and classified as a first-degree archaeological site in 2011.

The Geliyê Godernê (Godernê Valley), with its rich biodiversity and history dating back to the Neolithic period, serves as a collective memory of the region’s living history. It is regrettable that the planned Silvan Dam has resulted in the felling of trees in the valley and the use of dynamite, which has caused irreparable damage to the natural environment. Given that a portion of the valley will be submerged upon completion, it is vital to safeguard this invaluable human heritage.

Hazro is also renowned for its Kurdish kilams, stranbêjs and dengbêjs, who serve as custodians of oral cultural traditions.

A kilam is a narrative that has been experienced first-hand, imbued with anguish and articulated with a desolate tone, according to some, to the mountains. A dengbêj performs a song that evokes sentiments of love and rebellion. There exists an intangible, unidentified connection between the mountains and this tradition. The dengbêj represents the collective voice of the people, who in their pursuit of overcoming the seemingly insurmountable, attempt to engage with the mountain in a gesture of peaceful resolution. Notable figures in this tradition include Fekî Süleyman, Ehmedê Bêsikê, Emînê Hacî Tahar, Dengbêj Arîf and Seyfettinê Kufercinê.

The song of the renowned dengbej Ehmedê Bêsikê from Hazro, Lê Dîlberê, is a poignant lament against the marriage of the woman he loves to another. It goes as follows: “Lê lê gewrê bedla şeveqê li imin zelal bû. Ez ê bala xwe didimê xelqa min a delal xwe da deve eywane, belek pişta xwe da usûnê, lê wî lê lê.”

Text: Muharrem Erbey

Translation: Özgür Bircan

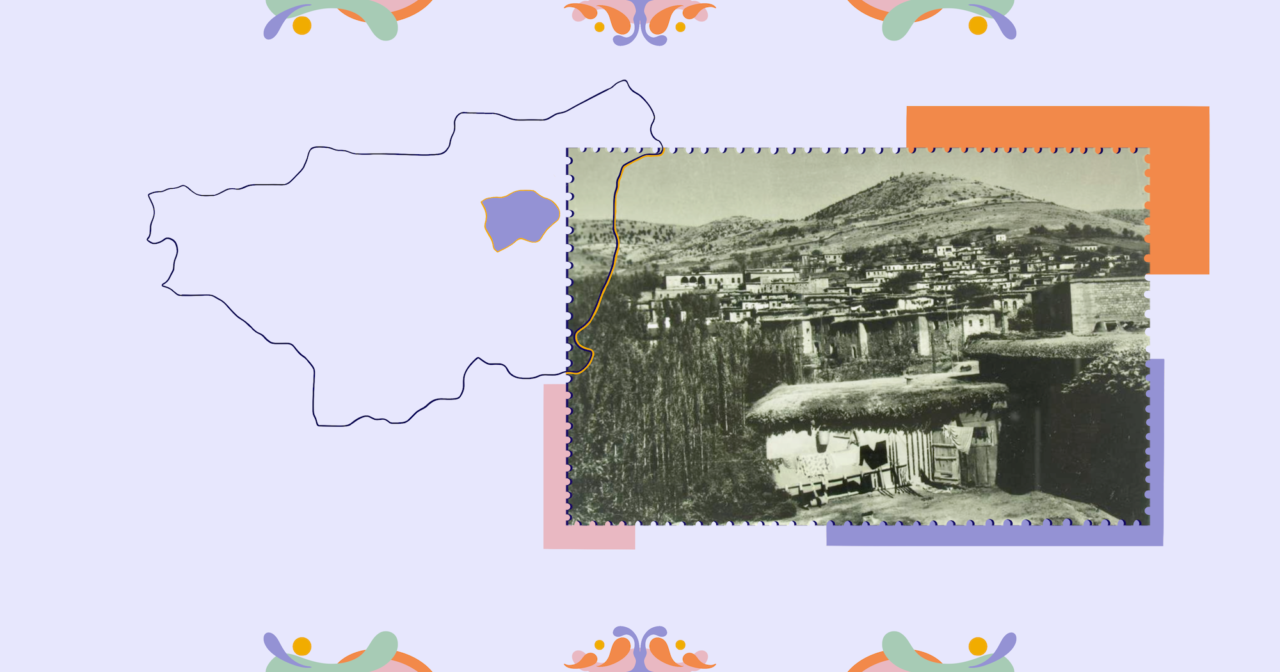

Cover photograph: Hazro, Şevket Beysanoğlu Collection, DKVD Diyarbakır City Archive

BIBLIOGRAPHY

• “Ayn Dar Kalesi’nin gizli geçidi [The Secret Passage of Ayn Dar Castle]”, Norm Haber, 2023.

• Beysanoğlu, Ş. (2003) Anıtları ve Kitabeleriyle Diyarbakır Tarihi [Diyarbakır History with its Monuments and Inscriptions], Diyarbakır Metropolitan Municipality.

• Bozan, O., Ertekin, A. and Yaz, A. (ed.) (2024) Antikçağ’dan Günümüze Medeniyetler Kavşağında Hazro [Hazro at the Crossroads of Civilisations from Antiquity to the Present], Çizgi Kitabevi.

• Evliya Çelebi (1998) Seyahatname [Book of Travel], Yapı Kredi Yayınları.

• The website of the Hazro District Governor’s Office, 2024.

• Hazro District Governorship (1998) Zuğur’un Ötesi: Hazro [Beyond Zuğur: Hazro].

• Helimoğlu Yavuz, M. (2018) Diyarbakır Efsaneleri [Diyarbakır Legends], Kaynak Yayınları.

• İzgörer, A. Z. (ed.), (1999) Diyarbakır Salnâmeleri [Diyarbakır Annals], Diyarbakır Metropolitan Municipality.

• Muhammed Emin Zeki Beg (2014) Kürtler ve Kürdistan Tarihi [Kurds and History of Kurdistan], Nûbihar Yayınları.

• Pekol, F. (2017) Zirki Beylikleri ve Beyleri Tarihi [History of Zirki Principalities and Beys], Master’s Thesis, Mardin Artuklu University, Institute of Social Sciences, Department of History.

• Sadak, C. and Akyol, H. (ed.), (2007) Antolojiya Dengbêjan / Dengbêj Antolojisi [Anthology of Dengbêjs], Diyarbakır Metropolitan Municipality.

• Şerefhan (1990) Şerefname: Kürt Tarihi [Sharafname: Kurdish History], (translated by) M. Emin Bozarslan, Hasat Yayınları.

• Tîgrîs, A. and Çakar, Y. (2012) Amed: Erdnîgarî, Dîrok, Çand [Amed: Geography, History, Culture], Diyarbakır Metropolitan Municipality.

• Turkey Cultural Heritage Map, Hrant Dink Foundation, 2024.