Following restoration work that began in 2010 and continued for four years, the Cemil Paşa Mansion can be visited today as the City Museum, and it has many stories to tell. The first, of course, is the turbulent history of one of the ancient families of the city… Belongings of the Cemil Paşa family on display at the museum reveal the life-style of an upper-middle class family during several periods. The mansion bears further architectural worth in that brings into the present day the various aspects of traditional Diyarbakır houses.

The Cemil Paşa Mansion is one of the few buildings that resembles an island surrounded on four sides by streets in Suriçi [literally ‘inside the city walls’], the central neighbourhood surrounded by the city falls, which forces a congested order of settlement. It is an important structure in that it is an extant mansion retaining the authentic features of traditional Diyarbakır houses.

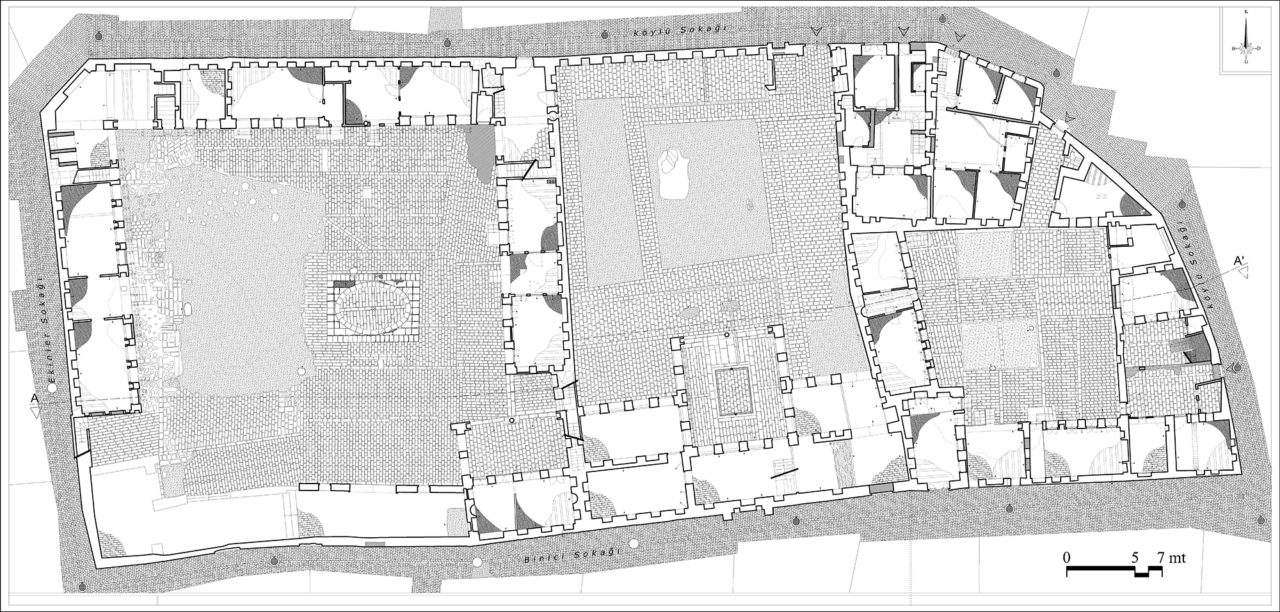

The mansion is divided into the harem (the space reserved for women), selamlık (the space reserved for men) and service sections. The harem section is made up of the four wings surrounding the large rectangle courtyard in the middle. A significant part of the southern wing collapsed around a century ago. In the other wings there are the iwan, rooms, kitchen, toilets, warehouse and hamam (bath) units. The selamlık is between the harem and service sections, and is composed of the large iwan in the south with open on three sides and the two-floor section behind it. The service section in the east is formed of spaces surrounding the courtyard and has been separated into four parts today because of property conflicts. In addition to the harem entrance, there are other street entrances in the north and south to the building.

From the squinch stones above the entrance gate of the selamlık section, we read that the construction of the mansion began in 1887-1888 (1305 according to the Islamic calendar) and was completed around a year later. It is also written above the two-winged wooden door of the selamlık section that Cemil Paşa passed away in 1902.

Associate Professor Meral Halifeoğlu, Restoration architect

When the subject is Kurdish political and cultural life in Diyarbakır in the early 20th century, the Cemil Paşa family immediately comes to mind. The family came from the Cizre-Silopi area around four centuries ago, and settled in Diyarbekir. Family members have both written and said that their roots lead back to the Azizans of Cizre. Since the last powerful head of the family in Diyarbekir was Cemil Paşa, who passed away in 1902, they are known as the Cemilpaşazades. In addition to properties in the centre of Diyarbekir, Cemil Paşa also controlled twenty villages in the Ambar Creek (Çemê Embarê) area in the east of the province.

Seîd Veroj, Writer

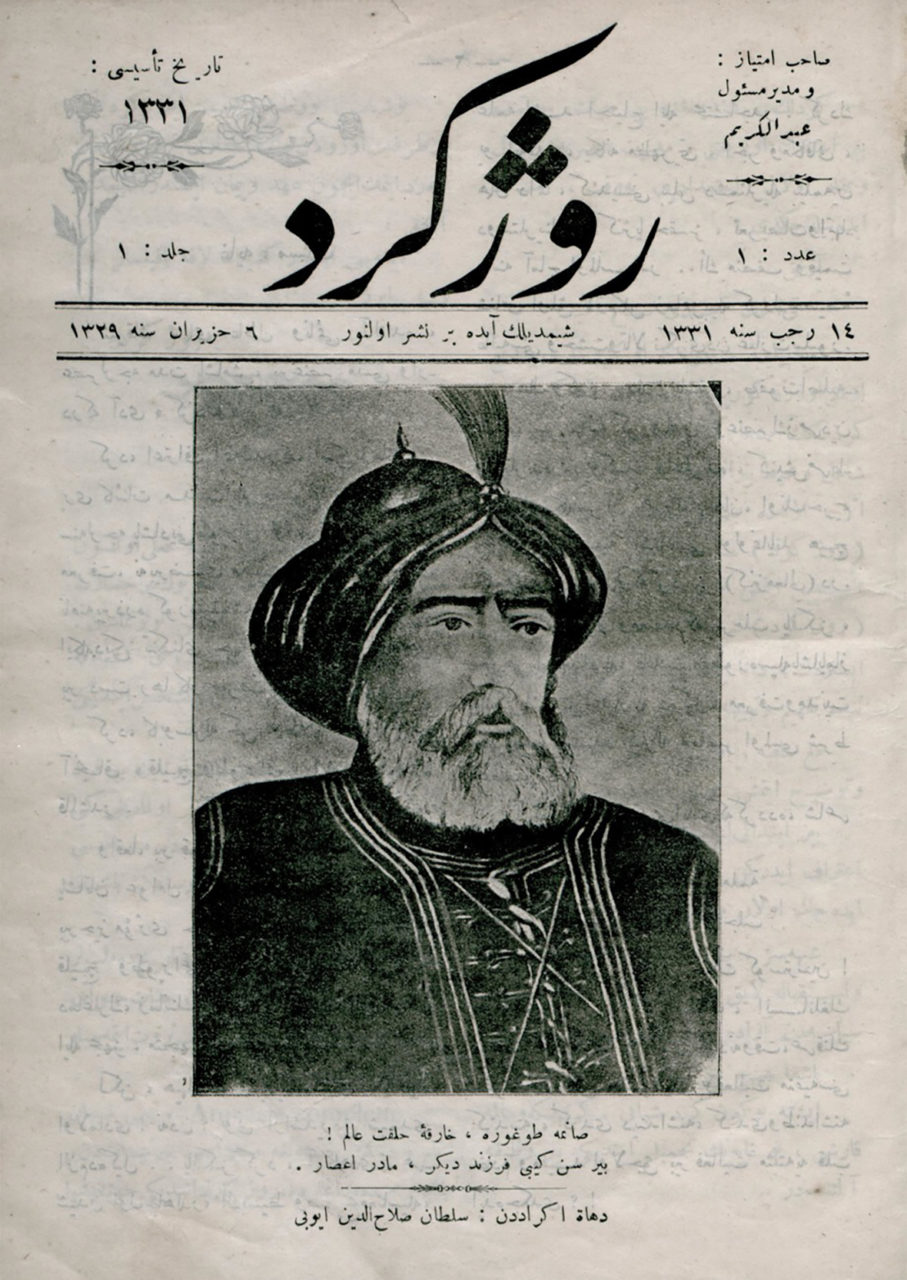

In the beginning, like many Kurdish scholars, intellectuals and members of important families, Cemil Paşa’s children, too, supported the constitutional monarchy movement against Abdul Hamid II’s tyranny. However, when the Party of Union and Progress opted towards Turkish nationalism, like other Kurds, they, too, moved away from this movement. This was also the time when Cemil Paşa’s family participated in the Kurdish cultural and political movement. We also see members of the Cemil Paşa family in many Kurdish organizations founded after this date. In the Hêvî Kurdish Students’ Association founded in 1912 in Istanbul by Kurdish students, a total of six individuals, three founders and three members, were from the Cemilpaşazades. The Lausanne/Switzerland branch of the Hêvî Association was the first Kurdish organizational representation abroad.

The Society for the Rise of Kurdistan was founded in late 1918, following the end of World War I; and its Diyarbekir branch that brought together a significant part of Kurdish nationalists was also established under the leadership of the Cemilpaşazades. During periods of political repression and prohibitions, when first, the Istanbul government, disturbed by these activities, gradually closed all associations, and splits took place among the movement, and later when a search for unity took place once again, Cemil Paşa family members assumed active roles.

Seîd Veroj

• Ekrem Cemil Paşa (1989) Muhtasar Hayatım, Beybun Yayınları, Ankara.

• Kadri Cemil Paşa [Zinar Silopi] (1991) Doza Kurdistan, Özge Yayınları.

The Diyarbekir trials at the special Independence Tribunal had become a direct threat to the lives of Kurdish patriots. Detained Cemil Paşa family members were sentenced to imprisonment and exile because they had not actively taken part in incidents. Despite the amnesty issued later, family members were not allowed to return to Diyarbekir, and those who did live there were forced to leave the city under political repression. In Syria, too, where a large part of them migrated to, the family continued to stand at the forefront of the Kurdish national struggle, in the Xoybûn organization founded in 1927. This political line gave its support, from the very beginning, to the Republic of Kurdistan declared in 1946, with the city of Mahabad as its capital, and its relationship with Chief of General Staff Mustafa Barzani continued to improve.

Seîd Veroj

• Ekrem Cemil Paşa (1989) Muhtasar Hayatım, Beybun Yayınları, Ankara.

• Kadri Cemil Paşa [Zinar Silopi] (1991) Doza Kurdistan, Özge Yayınları.

When we look at the life style and social relationships of the family, we observe a family that displays both an aristocratic standing, and stands close to the people. There were more than twenty ladies, around twenty servants and workers, and more than thirty children living at the (harem section of the) mansion. Other than a few Assyrian secretaries, all the servants were villagers who did not speak Turkish. Dengbêjs (folk poets), çîrokbêjs (story tellers), tamburvans (tambour players) and bılurvans (kaval, or flute players) were frequent visitors of the mansion.

One of the most important aspects of the Cemil Paşa family was that the literacy and educational level was higher than other great Kurdish families of their period. Ekrem Cemil Paşa, who himself had studied electrical engineering at the University of Munich, writes as follows: “The sons, daughters and grand children of the Cemilpaşa family had all been educated. Cemil Paşa did not have a single illiterate child.”

Children were treated equally in their preference of schools; if an Assyrian or Armenian school was chosen, the children would be enrolled there. In the years 1912-13, five individuals from the Cemil Paşa family, Cevdet, Kadri, Ekrem, İbrahim and Şemsettin were studying in Europe.

Seîd Veroj

• Ekrem Cemil Paşa (1989) Muhtasar Hayatım, Beybun Yayınları, Ankara.

• Kadri Cemil Paşa [Zinar Silopi] (1991) Doza Kurdistan, Özge Yayınları.

As in all Kurdish culture, the guest, and hospitality were important concepts for the Cemil Paşa family. Whether in Diyarbekir, or later in exile, the door of the family was always open to everyone, and they had guests from all social sections. Politicians, smugglers and even conflicting parties to blood feuds would visit them. In greeting guests, there were three fundamental rules that all family members had to abide by: First, no one would ask the guests their names. Second, it was prohibited to ask them where they came from. And finally, it was also forbidden to ask them when they would be leaving.

Seîd Veroj

Private interview carried out on 15.12.2018 with family member Ferda Cemiloğlu.

(The archive of Ferda Cemiloğlu)

Another important aspect of the life of the Cemilpaşazades was the collective internal economic relationships at a mansion where, other than temporary guests, more than hundred people lived together. Whoever had been born at the house, or whoever was living there, benefited from the mansion’s cash strongbox in accordance with their needs. There was a blue strongbox with a drawer at the mansion which has accessible by all, and at the start of every month, a certain amount of money would be placed in that drawer. Those going to school, going shopping to the markets, needing to spend for the kitchen, and even those who needed pocket money, everyone would take enough money from that drawer. If money ran out in the drawer towards the end of the month, those who had money left would put some back into the drawer, so that ends could be met until the start of the next month.

Seîd Veroj

Private interview carried out on 15.12.2018 with family member Ferda Cemiloğlu.

There were around thirty children at the Cemil Paşa Mansion and they were divided into three girl-and-boy-mixed groups. Since the mansion was large and crowded, a whistle was used to effectively direct children especially during dinner time and at school and study hours. This was a silver whistle embellished with special decorations.

Boys who reached the age of twelve would often be taught the javelin throw, accompanied by a master horse rider. Every year, children would always spend two-to-three months during the summer holiday at the village.

Seîd Veroj

Private interview carried out on 15.12.2018 with family member Ferda Cemiloğlu.

“Until I reached the age of 21, I lived in a magnificent mansion that resembled a palace, a castle, and perhaps also a military barracks, known as the Cemil Paşa Mansion. The harem section of this magnificent mansion was home to more than twenty ladies, around twenty servants and workers and more than thirty children. There were also more than twenty servants in the selamlık section: Coffee makers, room servants, table servants, apprentices…

In the flower gardens of the harem and selamlık sections, other than ornamental trees like acacia and lilac trees, there were around forty fruit trees including apple, pear, apricot, peach and mulberry trees. In every section, there were fountains and with water running day and night. We children learned to swim in those pools. We children were divided into three groups. The group I was in had eleven boys and three girls. The children who were four-five years older than us had a smaller group. And the youngest children had the most crowded group. There were also many babies in the cradle. Everyone would mingle, sit and play with their own age group. Of course, the youngest were always accompanied by their dains (nannies). On many days, and especially on Fridays, many children of relatives and neighbours would be added to this crowded group of children.

After lesson hours came play hours, and the many children of Cemil Paşa would have a joyful, cheerful time together. Those who were over the age of ten had the right to climb trees. They would collect fruit from the trees, eat them and give them out to their grandmothers, mothers, sisters and brothers and servants accompanying them. As the children grew older, their games and forms of entertainment developed as well. Damascus donkeys of various sizes had been brought in to teach children horseback riding from the age of eight on. The selamlık section had a stable. This section featured a courtyard, a breeding barn, a hay barn and stables of various sizes.”

From the memoirs of Ekrem Cemil Paşa, a grandson of Cemil Paşa

Ekrem Cemil Paşa (1989) Muhtasar Hayatım, Beybun Yayınları, Ankara.

Although there were haremlik and selamlık sections in the architectural sense at the Cemil Paşa Mansion, the division was not based on a conservative outlook. Women were not treated as second class and were not forced into a passive position. A member of the family born in Syria in exile, Ferda Cemiloğlu presents the following example:

“When we look at the photographs of some of the great families of Diyarbekir, we only see men, there are no women in the photographs. However, if we look at a photograph of our family taken in 1875, women and men are together. In the photograph, in addition to Cemil Paşa and his eleven sons, his three daughters also take their place.”

The same was true for property sharing and inheritance. When the family gained property, the hammams (baths), hans (trade buildings) and homes would be registered under the name of women. In order to economically protect women who were getting married, significant amounts of jewellery and ornamentation would be gifted to them, and each item would be registered with the signatures of members of renowned aristocratic families of Diyarbekir. In a rarely encountered approach, at the foundation established by the family, only women were given support salaries.

Seîd Veroj

Private interview carried out on 15.12.2018 with family member Ferda Cemiloğlu.

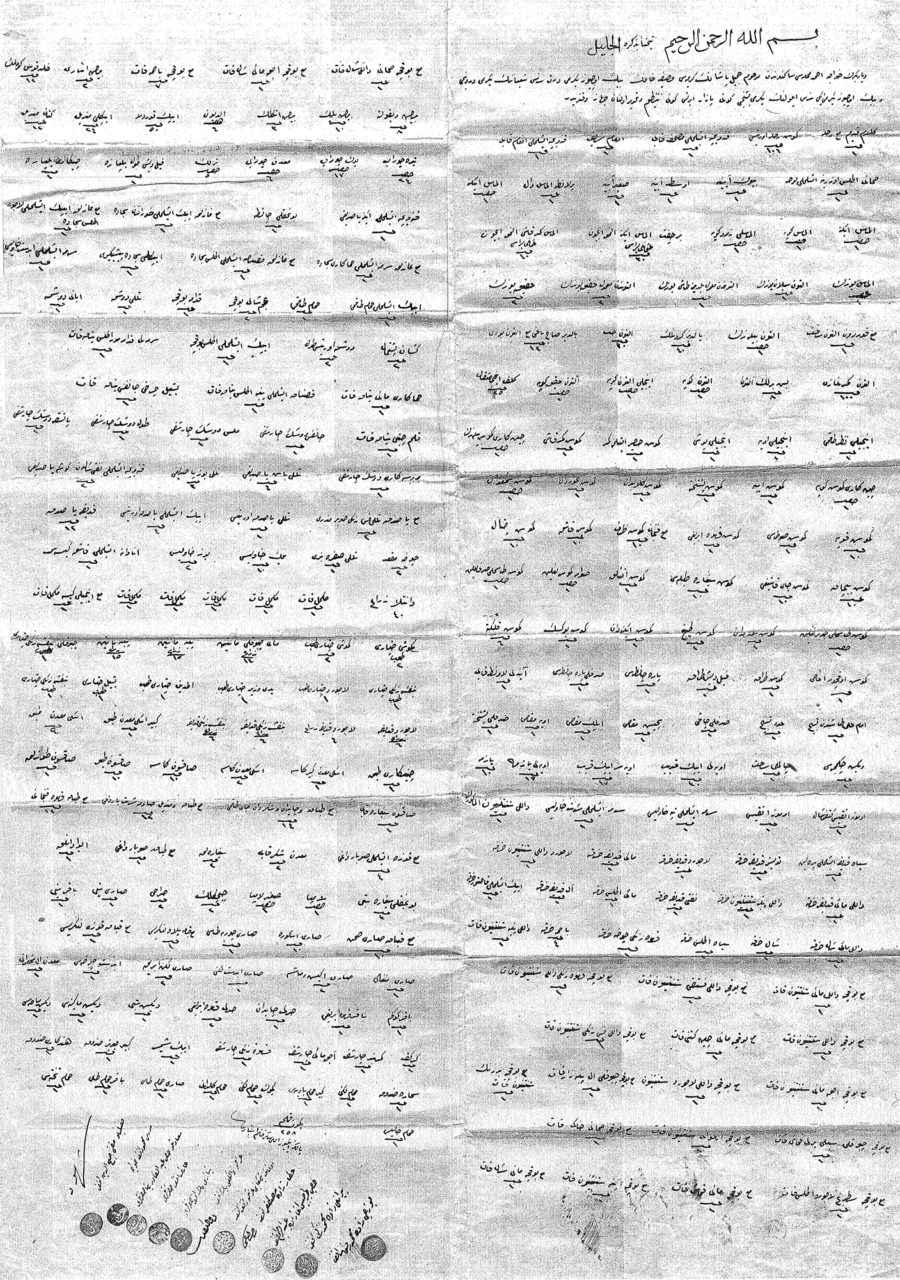

Ferda Cemiloğlu, a member of the family, possesses an old dowry book. The document begins by stating, “This is the dowry book of Vasife Hanım, daughter of the late Cemil Paşa, resident of the Hoca Ahmed neighbourhood of Diyarbekir, and has been drawn up on the 24th day of the month of Şaban in the year 1324, and the 25th day of the month of September in the year 1322 (8 October 1906), Monday”. A total of 258 items are included on the list prepared in the presence of witnesses.

The abundance of jewellery and ornamentation is striking, with brooches, earrings, rings, bracelets, necklaces, hair bands, wristwatches and belts made of diamonds, gold, cut diamonds, pearls, or silver. Silver is the preferred material for many tools used in everyday life. A silver water bowl, percolator, eye-liner holder, needle, thimble, mirror, gülâbdan (bowl to sprinkle rose water), candelabra, spoon and thimble are just a few of these.

From pearl-embroidered headscarves to broadcloth cardigans, and from ketefi shawls to ala furs (made from the valuable parts of fox fur, almost as expensive as sable fur) and various types of fabric for dressmaking form a significant part of the list.

The diversity is explained better in the following list:

Line 2 – 8 white décolleté dresses, 10 white silk dresses, 3 white petticoats, 6 pairs of gloves, 50 silk ribbons, 24 silk handkerchiefs, 12 (…) handkerchiefs.

Line 5 – 1 prayer rug brocaded in the Hamakari style, 1 satin prayer rug embroidered in the Kazazi style, 1 silk prayer rug in the Pişbikeri style, 1 brocaded ablution towel.

Line 8 – 1 blue mattress in the Hamakari style, 1 hoop-embroidered pink satin mattress, 1 green taffeta mattress.

Line 12 – 2 broadcloth seats, 1 wired tablecloth, 10 dinner towels, 2 face towels, 1 spoon pouch embroidered in the Anavata style.

Line 13 – prayer beads made of Imam Ali stone, prayer beads made of emeralds, 1 jack-knife decorated with mother-of-pearl, 1 pair of buttonhole scissors, 1 pair of embroidery scissors, 1 tray decorated with mother-of-pearl

Line 18 – 1 Saxon cigarette case, tea set with 14 plates, tea pot and sugar pot, 12 plates and sherbet glasses, 12 coffee cups and base plates.

Transcription: Toygun Altıntaş

(The collection of Ferda Cemiloğlu)

The family ascribed great importance to jewellery made of valuable metals or gemstones such as gold, silver or ruby. Expensive jewellery was also used as a ready source of cash to meet needs at any emergency.

Specially commissioned, some of the ornaments would feature local and national symbols. The most striking symbol of all was the green scorpion unique to the Diyarbekir region. The green scorpion is said to help determine direction, and since it is endemic to Diyarbekir, it is a symbol of the city’s culture.

Seîd Veroj

Private interview carried out on 15.12.2018 with family member Ferda Cemiloğlu.

As part of Kurdish culture, tobacco and cigarette-smoking held a special place in the life at the mansion. In such grand houses, there would be special sections for tobacco to be categorized in accordance with its humidity, or full-bodied, medium or mild qualities, and tobacco would be kept in separate places by age. As other product was kept to “mature”, tobacco aged to ten years would be used first, and only then would the more recent product be smoked.

The two most important aspects in cigarette preparation are hygiene and aroma. A special adhesive and a brush was used to stick the paper together; it was never wrapped using saliva. This adhesive, prepared by boiling quince seeds would also add aroma to the cigarette. This was a cultural practice unique to Diyarbakır. Tobacco would be mixed using a special tool, and would not be handled. Silver sticks placed in tobacco bowls would indicate, according to their qualities and varieties, from which region the tobacco came, and who it belonged to. Silver was preferred because it did not produce bacteria. Considering the possibility of cholera epidemics, silver was also preferred because of this quality in the wider production of silver cups, pots and pans.

Cigarette holders made from valuable materials and of diverse design would be used for the smoking of cigarettes. There were special cigarette holders for women, and some holders had finger rings to prevent nicotine staining of the fingers. As much as cigarette holders, tobacco boxes, lighters and match holders, too, would be made of various valuable metals. Like many other handcraft products in Diyarbakır, these, too, were the work of Armenian masters.

Seîd Veroj

Private interview carried out on 15.12.2018 with family member Ferda Cemiloğlu.

During the period when the rightful heirs of the Cemil Paşa Mansion were forced to leave Diyarbakır, a family that acted as keepers lived in a wing of the harem section until the 2000s. Since the selamlık section was not used at all for a long period of time, it had been entirely abandoned. As for the service section, since it had been sold to four different families, the unique architecture of the structure had been damaged due to many additions, blockages and divisions. Since it had not been used or maintained for a long time, the structure had been seriously deformed. The south wing of the harem section had largely collapsed.

Meral Halifeoğlu

The restoration work that began in the year 2010 at the harem and selamlık sections of the mansion continued for four years. Under the supervision of the Diyarbakır Museum Directorate, surface cleaning and partial research excavation was carried out at the collapsed south wing of the harem section. Work at this excavation was assessed along with data from the 1999 excavation. The Cemil Paşa Mansion displays the traditional construction technique and culture of everyday life of Diyarbakır down to the smallest detail, and following the completion of the restoration work, the building was turned into the City Museum. In addition to objects that belong to Cemil Paşa and his family, visitors are presented with information about the history, literature, art, music, food and many other aspects of Diyarbakır.

Meral Halifeoğlu

Translation: Nazım Dikbaş

![Members of the Cemil Paşa family had been sentenced to imprisonment and exile by the special Independence Tribunals [İstiklâl Mahkemesi] and thus forced into exile in Syria. Ferda Cemiloğlu on horseback. (The archive of Ferda Cemiloğlu)](https://diyarbakirhafizasi.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/4_Cemilpasa.jpg)