Diyarbakır, where the first human settlement dates back almost ten thousand years, has always stood at an important point of intersection at the northern boundary of Mesopotamian civilizations and the southern boundary of Anatolian ones. This particular location created fertile grounds for cultural diversity as much as it brought political activity and commercial dynamism to the city. Such crossroads have always been places frequented by travellers, way stations for a brief respite. Their accounts, therefore, allow for the writing of an ‘other’, alternative history of these lands.

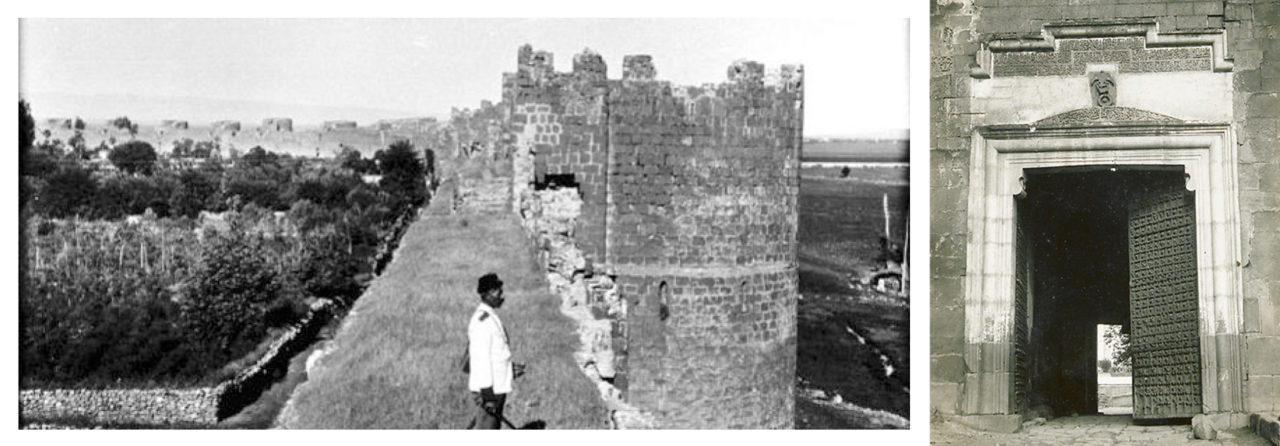

Diyarbakır had its fair share of visitors of this kind. Some were impressed by its architecture, others its geography. Some wrote, “I know of no other place better fortified and of more critical standing possessed by the Muslims on their frontier.” Others were unable to hide their admiration, saying “I have seen many a city and fortress around the world in the lands of the Arabs, Persians, Hindus, and Turks, but never have I seen the likes of Amid on the face of the earth or have I heard anyone else say that he had seen its equal.”

Accounts, in particular, by travellers who passed through the region from the mid-Medieval period up to the establishment of Ottoman rule reveal traces of the many changes experienced by the city.

Each and every traveller visiting Diyarbakır, then called Amid, had their own particular reason for setting out on the road. Geographer al-Maqdisi (also known as al-Muqaddasi), for instance, came here in 985 for field research and noted down the following on this city he likened to Antioch:

“… A city with a beautiful, sturdy and interesting structural style, Amid bore great resemblance to Antioch. It had outer walls that looked like a large platform, studded with gates and turrets. Between the outer walls and the citadel lay an empty stretch. Yet Amid was smaller in size than Antioch. The city walls were of hard black stone. The foundations of houses were also built of this stone.

Inside the city one could find many water sources. Amid sat on the western banks of the Tigris. A quite pleasant and prosperous city, Amid functioned as an important frontier town for Muslims and a fortress they garrisoned. The mosque was situated right in the middle of the city.

The city had a total of five gates. These were the Water (Tigris) Gate, the Mountain (Dağ) Gate, the Rum Gate (Gate of the Greeks), the Hill (Tell) or Mardin Gate, and the Sneaking (Sır) Gate – which was a smaller postern gate used as a secret pass during times of war. The citadel was partially nestled on a mountain. I know of no other place better fortified and of more critical standing possessed by the Muslims on their frontier today.”

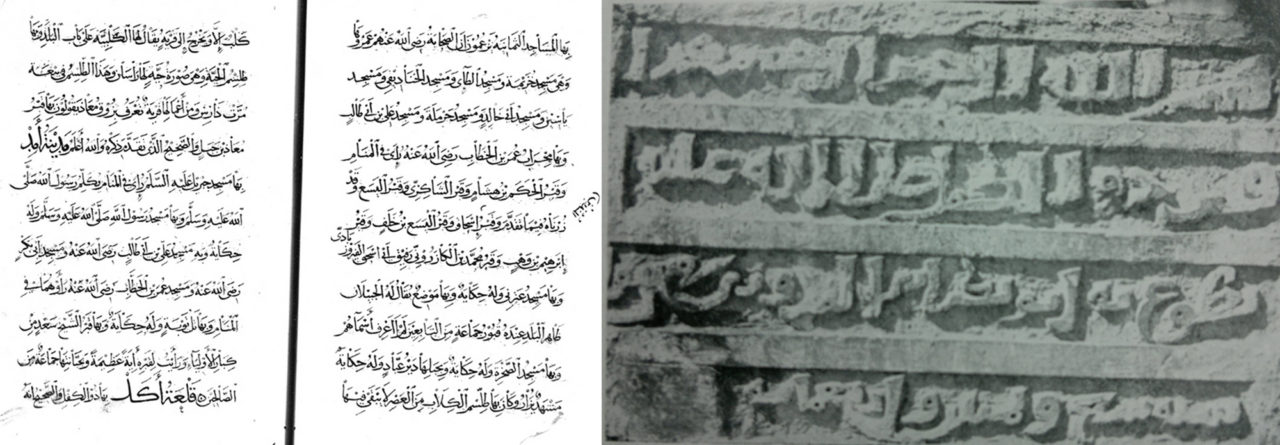

Abu Abd-Allah Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Maqdisi (or al-Muqaddasi), Aḥsan al-taqāsīm fī maʿrifat al-aqālīm (The Best Divisions in the Knowledge of the Regions), circa 1000, (ed.) M. J. de Goeje, E.J. Brill, Leiden, 1906.

On the right: The wings of the wrought iron Urfa Gate bearing stylized animal figures.

Notes taken by Nasir Khusraw, who stopped by Amid on his pilgrimage route to the Hajj in 1046 as the city was at one of the heights of its glory under the Marwanids, have also made it to our day.

“The city sat atop a block of solid rock. It stretched over a length of two thousand paces from one end to the other, with a near equal breadth. Walls were erected around the city’s circumference, built of black stone with each slab weighing from a hundred up to a thousand – or perhaps more – batmans (an Ottoman unit of mass also known as ‘maunds’). These stones fit together exactly, with no lead or lime mortar to bind them. The wall is twenty arshins (Ottoman ‘yard’) in height and up to ten arshins in breadth. At every hundred paces along the wall are semi-circular towers with a radius of eighty paces each. The battlements on these crests have been made of the same stone. The many stone gangway steps leading up to the ramparts from the city on the inner side are adjacent to the wall. On every tower, ample space has been provided for soldiers to fight.

The city had four entrance gates. These gates were all cast in iron without wood. Every gate stands facing one of the cardinal directions. The one to the east they called by the name of Tigris (Dicle) gate, the one to the west the Greek (Rum) gate, to the north the Armenian (Ermen) gate, and to the south the Hill (Tell) gate.

Beyond these walls were inner walls of the same stone, ten arshins (yards) in height. All city walls had battlements, and passageways leading up to them were built wide enough for a totally armed man to pass and to stop and fight with ease. These inner walls too had iron gates corresponding to those on the outer ones. There was a ring of land anyone passing through an outer gate had to walk through in order to reach an inner gate. This distance measured fifteen paces.”

Abu’l-Mu’in Nasir ibn Khusraw ibn Harith, Safarname-i Nasir Khusraw al-Qubadiani al-Marwazi (Nasir Khusraw’s Book of Travels), 1088, (ed.) Muhammad Dabir-Siyaki, Intisharat-i Zawar, Tehran, 1990.

Nasir Khusraw finds himself unable to liken the Amid he explored in 1046 to any other city he ever saw. He was particularly impressed by the Great Mosque.

“In the center of the town a great spring of water of excellent quality, sufficient to turn five mills, gushed out of a granite rock. Nobody knew where this water came from. Its overflow irrigated the neighbouring gardens and trees. The city is governed by the afore-mentioned son of Nasr al-Dawla (Marwanid). I have seen many a city and fortress around the world in the lands of the Arabs, Persians, Hindus, and Turks, but never have I seen the likes of Amid on the face of the earth or have I heard anyone else say that he had seen its equal.

The Great Mosque is made of the same black stone, and a more perfect, stronger construction cannot be imagined. Inside the mosque stand two-hundred-odd stone columns, all of which are monolithic. Above the columns are stone arches, and above the arches is another colonnade shorter than the first. Above that is yet another row of arches. All the roofs are domed, and all the masonry is embellished with woodwork, carving, ornamentation and painted with designs.

In the courtyard of the mosque is placed a large stone atop which is a large, round, stone basin. It is as high as a man, and the circumference is almost two yards (ten ells). From the middle of the pool protrudes a brass waterspout from which shoots clean water; it is constructed so that the entrance and the drain for the water are not visible, and have not been found.

The enormous ablution pool is the most beautiful thing imaginable. While this ablution pool in Amid was of black stone, the stones used in the one in Mayyafariqin were notably white.

Nearby the mosque stood a great church, built of stone and paved with marble. At the entrance of the domed basilica of this church where Christians worshipped I saw a latticed iron door, the likes of which I had never seen before.”

Though his name has not made it to our day, we do know that an anonymous traveller we gather to have lived in the Artuqid period toured the region with the help of a book of geography he had found. In addition to his observations of the city in the year 1183, the traveller also makes striking assessments as to the sociological situation.

“… Amid is a town situated west of the river Tigris on rocky ground in a commanding position at a height matching that of fifty men. It is surrounded by black city walls made of millstone (basalt). Due to the jet black hue of this stone, the city has taken on the name “kara” (black). This stone had no equal on the face of the earth. Millstone that bore some resemblance to it would be sold for around 50 gold dinars in Iraq. Within the city walls were three springs. Water flowing from these turned a great number of mills immediately after leaving its source. There were vineyards and high-quality fruit orchards in the city. Formerly an important frontier town, there were hence numerous charitable endowments/trusts (waqf) made for the purpose of the upkeep of the Amid city walls.

The author of these lines attests: when I first came to this city in 1139, there were but a handful of people left in it. While it used to be home to prominent noble families, religious notables, philosophers, writers and generous men of wealth, the cruelty and tyranny of the Nisanids (family of Nisan), their imposition of taxes of unprecedented weight, the oppression they subjected on the people, and their confiscation of the property of those unable to pay these taxes forced many to now abandon their homeland and move elsewhere. Families have been torn apart, houses destroyed, with not even a trace left behind. Shops closed down one by one and marketplaces went dead. Above all, the city gained a bad reputation. Hence, as citizens left from fear of suffering harm and went to foreign places, not only did they change their names but they also kept their hometown a secret.

Finally, wise and just Artuqid ruler Nur ad-Din Muhammad ibn Kara Aslan ibn Davud ibn Sokman conquered this city in the month of April of the year 1183. As he reopened the city gates to its people, he also lifted the heavy tax burden imposed. He brought an end to measures and practices causing suffering. He is trying to restore the city to its former glory with good services that seek to erase the marks of troubled times. While some destroyed parts have been rebuilt, areas that currently lie deserted shall flourish and prosper once again with the return of their inhabitants who left and the establishment of just rule over the city. God willing, he succeeds in doing so.”

Abu al-Qasim Muhammad ibn Hawqal al-Baghdadi, Kitab Surat al-ard (Opus geographicum), 977, (ed.) J. H. Kramers, Leiden, 1939.

The multi-faith character of the region also attracted those who wished to come to Amid for such purposes. Egyptian Coptic priest Abu al-Makarim ibn Jirjis too arrived here in 1204 in order to visit its Christian places of worship and recorded what he saw.

“… The city walls of Amid were of black basalt stone and impenetrably solid in both length and breadth. It had seventy bastions, and inside the city were nearly seventy places of worship belonging to Christians. One of these was a sturdily-built high structure, a church known by the name of the Sacred Virgin Mary.

This church had a dome of enormous proportions, and its interior was covered in frescoes and paintings, with a floor of glass mosaic tiles. Seventy Roman patriarchs had taken part in the creation of this mosaic. The church contained seventeen altars and a single portico, with the largest altar located at the center of this portico. There were seven column-like wooden posts holding up the church ceiling. The palace in Amid was larger and more spacious than the one built by the Fatimids in Cairo. The entire palace had been paved both ways in coloured marble and studded with glass mosaic tiles. The city of Amid had many other churches as well, but none the likes of this one. The Fortress of Amid had high walls protruding up into the sky.”

Abu al-Makarim ibn Jirjis, Tarikh al-Kana’is wa al-Adyirah (History of Churches and Monasteries), 13th century.

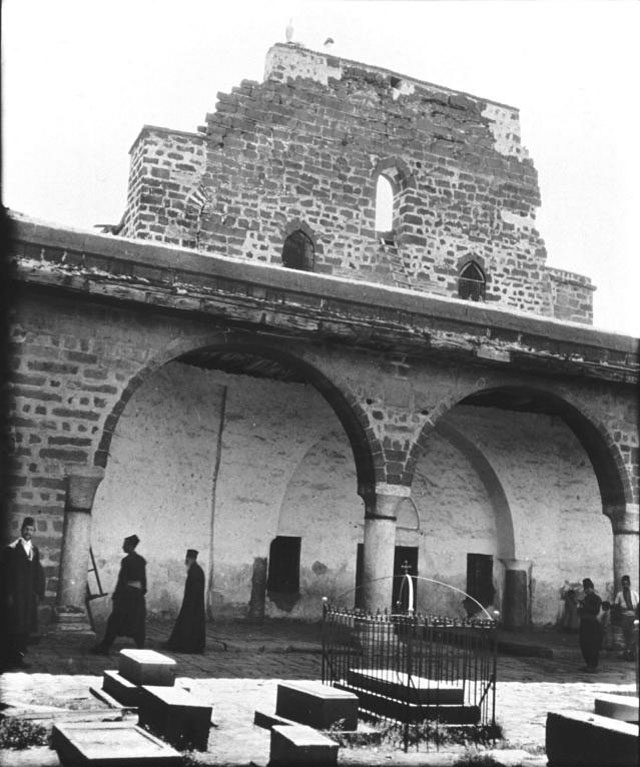

On the right: Tombstone dated 1095 prepared for the grave of Hazrat Zul-Kifl (the Prophet Ezekiel).

Muslim traveller Abu Bakr al-Harawi, who visited religious sites and compiled the information he had gathered on them in his book, also arrived in Amid in 1215 and conveyed his impressions in the following words:

“… In Amid there’s the Jibreel Masjid (Gabriel’s Mosque), the Nebi Masjid (the Prophet’s Mosque) – which has its story, and the Hazrat (Prophet) Ali and Hazrat Umar mosques. They have visited people in their dreams. There is a place named Tell Tevbe (the Hill of Repentance), which also has a story. There is a shrine (turba) in the name of Sheikh Sa’d, one of the great saints (awliya). Many dervishes take up lodging in the annex of this shrine. Though the Prophet Zul-kifl (Ezekiel) is said to be at rest at the Fort of Egil, this is not true.”

Ali ibn Abi Bakr al-Harawi, Kitab al-Isharat ila ma’rifat al-ziyarat (A Lonely wayfarer’s guide to pilgrimage), 1215, (ed.) Josef W. Meri, The Darwin Press, Princeton, 2004.

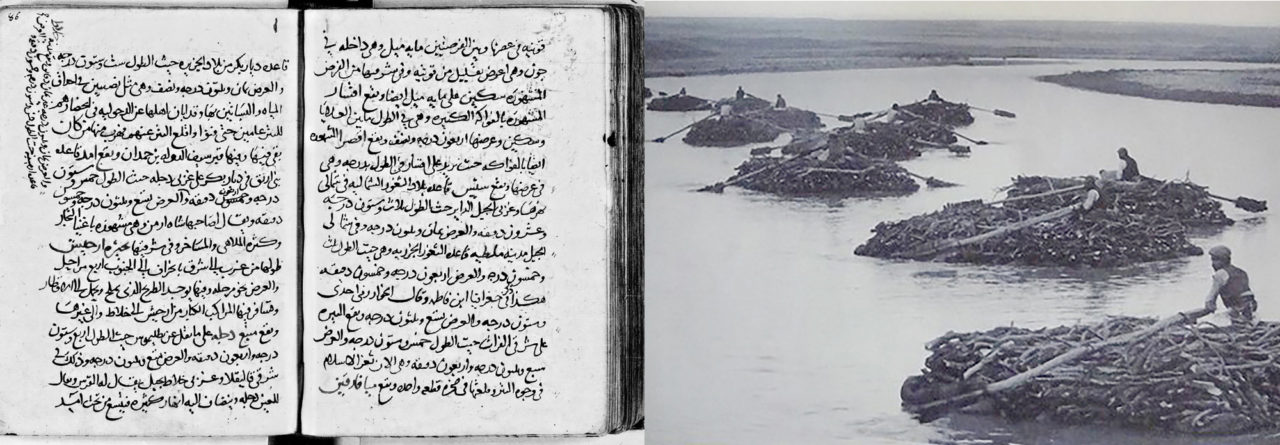

On the right: Kelekçi – raft/barge men – working the Tigris River on wooden rafts with inflated goatskins tied underneath. (Photograph from: the DITAV archive)

Ibn Sa’id al-Maghribi voyaged to Amid from afar, all the way from Spain. His writings from 1267 reveal that among the details that caught his attention here were the wooden rafts – or barges – used to navigate the Tigris.

“… Amid, which is the capital of the Artuqids ruling over the Diyarbekir region, sits on the western banks of the river Tigris, at a longitude of sixty-five degrees forty minutes and a latitude of thirty-eight degrees eight minutes. The Tigris, according to what we know from Ptolemy, is at a longitude of sixty-four degrees forty minutes and a latitude of thirty-nine degrees. These coordinates correspond to a mountain called al-Qarnayn (Bırkleyn) east of Kalikala (Erzurum) and west of Akhlat. The source where the river originates is known as ‘Tigris’. Many tributaries join this river, which widens beyond Amid. From this point onwards, keleks (a typical Tigris river craft, namely flat-bottomed barges/rafts) are lowered into the river. A kelek was simply a wooden raft with inflated goatskins tied underneath.”

Abu al-Hasan Nur al-Din ‘Ali ibn Musa ibn Sa’id, Kitab bast al- ard fi ‘t -t ul wa-‘l-‘ard (The Book of the Extension of the Land on Longitudes and Latitudes), 1286, (ed.) Havan Kirnit Hinis, Matbaatu Kerimadis, Tétouan, 1958.

Coming to Diyarbakır from Aleppo as a tax collector for the Mamluks in 1280, Izz ad-Din ibn Shaddad kept detailed notes as he carried out this duty. His lively and vibrant narration draws particular attention.

“… Amid is a city overlooking the Tigris, surrounded by two separate concentric walls, one of which is the larger barrier, while the other is smaller and more like a ridge. Ayyubid ruler al-Malik al-Kamil had this lower ridge-like wall torn down as he took control of the city and used the resulting debris for the fortification of the outer large wall.

This wall contains sixty bastions (towers) and five gates. These gates are the Hill (Tell) gate, the Water/Tigris (Su/Dicle) gate, the Faraj gate (Gate of Deliverance), the Greek (Rum) gate, and one more gate within the city walls. (Artuqid) Al-Malik al-Salih Mahmud had a fort constructed on the hill overlooking the Ayn Sora spring. The city walls are built of a hard, durable black stone, impenetrable to iron weapons. The ramparts were sized to accommodate five small-sized horses abreast. It is told that when Abu Musa Isa ibn al-Shaykh took control of Amid, Abbasid caliph al-Mutazid mounted an expedition here and laid siege to the city in the year 899. Once he conquered the city at the end of the war he had the city walls lowered. They remained so for a while. Later on, on one fine day, a man named Ibn Dimna who worked as a common porter in the city, was passing by the walls with a basket full of wheat on his back when he stopped to take a rest. He put his basket down and sat, contemplating the wall. Seeing how short it was, he said, ‘what a sturdy structure, if only its height weren’t so stunted! Dear God, if one day you were to make me the ruler of this town I would raise these walls by the height of one man.’ Time took its course and brought the meals of lowly folk to the tables of nobles. When (Marwanid) Mumahhid al-Dawla became ruler, he left the keys to his kingdom and the management of his domain in the hands of Ibn Dimna, who then kept his word and honoured his vow. Not only did he have the main walls raised, but he also had the inner walls rebuilt. This annexed portion of the wall has remained intact to date, as we write this book in the year 1280, and is clearly visible in certain parts. Many parts of the Amid city walls were repaired under the reign of Marwanid ruler Nizam ad-Din Abu al-Qasim Nasir ibn Nasir ad-Din ibn Marwan. The name of the ruler has been inscribed on both the inner and outer side of these restored sections.”

Abu Abd-Allah ‘Izz ad-Din Muhammad ibn Ali ibn Ibrahim ibn Shaddad, al-‘Alaq al-khatira fi dhikr umara’ al-Sham wa’l-Jazira (The Crucial Core in the Mention of the Rulers of Greater Syria and the Jazira), 1285, (ed.) Yahya Zakariya Abbarah, Wizārat al-Thaqāfah, Damascus, 1978.

While relating his personal observations, tax collector Izz ad-Din ibn Shaddad added pieces of information he thought would provide guidance to those charged with the same job after him.

“(Nizam ad-Din) had a bridge consisting of twenty-odd arches below rock constructed over the river Shatt/Tigris to the east of Amid. He endowed (as waqf) large swathes of land to meet the expenses for the restoration of the wall. There are two springs from which water flows in the city. One of these lies within the walls and is known by the name of Ayn Sora. Its source is unknown. Some say that it originates from Mount Lison (Karacadağ). The other spring is outside the walls, near the Greek (Rum) gate. It is known as Ayn Zaûra (the Little Spring/Anzele). A vaulted structure has been built in the midst of the spring by Marwanid ruler Mumahhid al-Dawla ibn Marwan. At some distance is another spring of water, named Bakilla. The water flowing from this source enters the city and is distributed via channels. Some of this water reaches the Great Mosque and fills the large basin within it.”

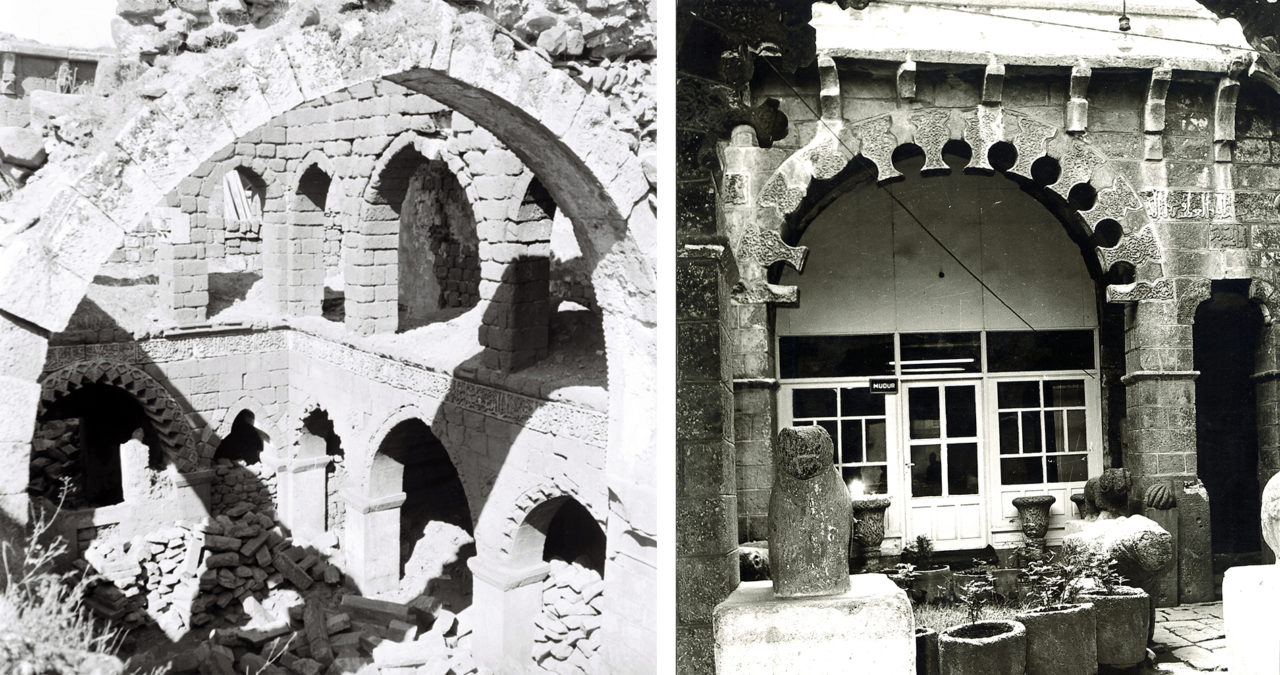

On the right: The Zinciriye Madrasa built for followers of the Shafi’i school. (Photograph by: Adil Tekin, 1970, the DTSO archive)

Coming to Amid as tax collector for the Mamluks in 1280, Izz ad-Din ibn Shaddad also relayed what he heard about a secret, mysterious tunnel.

“There are two madrasas in town. One is to the east of the mosque and is known as the Tajiyya Madrasa after Taj al-Din, the one who had it built. The other is close to the mosque and has two gates, one of which leads out onto the avenue and the other towards the mosque.

The city has two grand churches. One of these is in the vicinity of the Greek (Rum) gate and is known as the Church of (Mother) Mary. It is such an ancient and sturdy structure that this has made it famous. The other church is nearby the garden known as al-Menazî. It is said that before Muslims conquered the city there used to be a great church in this place. When the town was captured in war, the populace ran and took refuge in this church. Muslims pursued the fleeing folk into the church, but were unable to find anyone save for a woman standing at the entrance of a tunnel. When they asked her where everybody entering the church had gone, she said they had left through the tunnel. Apparently this tunnel led them to the land of Rum. This church was taken down in the time of (Artuqid) al-Malik al-Salih Mahmud, and some of its stones were reused to build the fabric market (bedesten/bezensteni). Its remains are enough to give an idea of the magnitude of the church’s dimensions.”

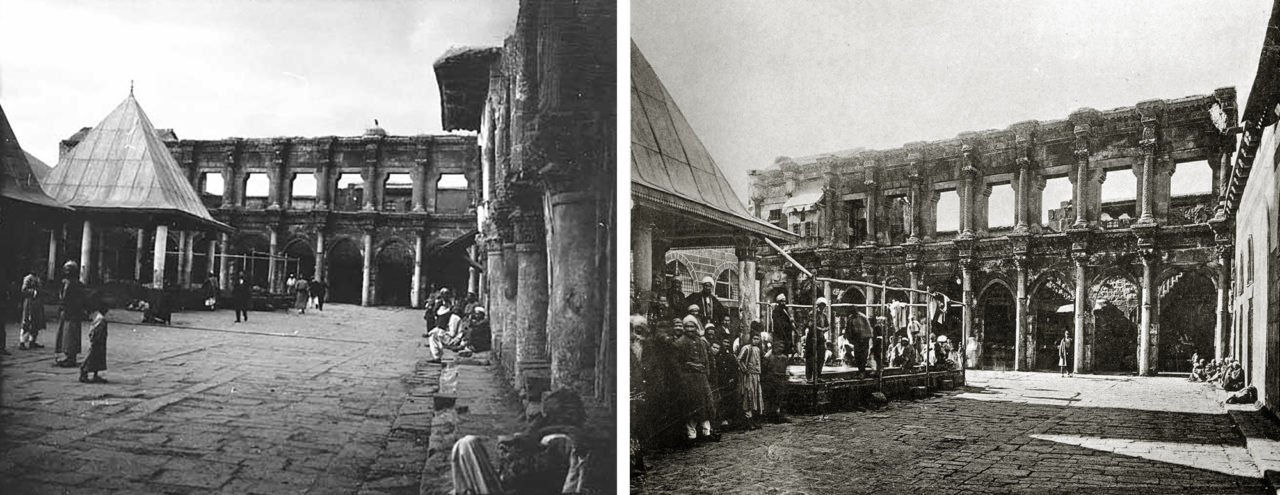

On the right: Dilapidated state of the Great Mosque. (Photograph by: Adil Tekin, the DTSO archive)

Diplomatic relations were also an important reason for travel back in those ages. Setting out from Egypt representing the Mamluks on an ambassadorial mission in 1472, Ibn Aja’s road to Aq Qoyunlu leader Uzun Hassan’s Tabriz palace took him through Diyarbakır as well.

“… We reached Amid from the Karacadağ side. I stayed in this city for all of Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday. After (Friday) prayers at the Great Mosque famous for its sturdiness and construction technique, I took my leave. Architecturally, this mosque resembled the Umayyad Mosque (in Damascus). Yet many of its important sections were facing ruin.

Edifices constructed by the Artuqids in their own era, on the other hand, bore witness to the efforts they had made for the flourishment of their domain. Looking at and reflecting in depth on these works of art and architectural structures, one clearly perceives the lofty and noble stance of the Artuqids and the value of the endeavours they undertook. And here comes to mind the poet’s words: Winds blew across the lands they called their home / As if meeting an appointment they had made all along…”

Muhammad ibn Mahmud al-Halabi Ibn Aja, within al-ʻIrak bayna al-mamalik wa-al-ʻUthmaniyyin al-Atrak, (ed.) Muhammad Ahmad Dahman, Dar al-Fikr, Damascus, 1986.

Being a merchant in the Middle Ages meant travelling endlessly for days, perhaps months. Such an anonymous Venetian merchant stopped by in Diyarbekir on his way to Tabriz in Iran in the year 1507 and committed to paper what caught his attention.

“…Three days’ journey from this castle (the Castle of Jumilen administratively bound to Orfa/Urfa) is the great city of Caramit, which, according to historians’ chronicles, was built by the Emperor Constantine, and has a circuit of ten or twelve miles. It is surrounded by walls of black stone, so placed, that it appears painted, and has in the whole circumference three hundred and sixty towers and turrets. I rode the whole circuit twice for my pleasure, looking at the towers and turrets of very different forms and sizes; still no one who is not a geometrician would not be pleased to see them, so marvellous are the structures; and in several parts on them I saw the imperial arms carved with an eagle with two heads and two crowns.”

Giosafat Barbaro, Travels to Tana and Persia and A Narrative of Italian Travels in Persia in the 15th and 16th Centuries, 1873, (ed.) William Thomas & Eugene Armand Roy, Cambridge University Press, 2010.

The same Venetian merchant was quite impressed by the places of worship the city had to offer for those of different religions and examined structures left from its Christian past with particular interest.

“There are here, also, people of many religious persuasions in greater numbers than Mahometans (Muslims-Mohammedans), namely, Christians, Greeks, Armenians, and Jews. Each religion has its separate church with its own service, without being molested by the Mahometans.

In this city are many wonderful churches, palaces, and marble monuments, inscribed with Greek letters. The churches are about the size of that of SS. Giovanni and Paulo or the Frati Minori at Venice. And in many of them are relics of saints and particularly of Saint Quirinus, which, at the time the Christians had the upper hand, were shown openly; and in the church of St. George I saw the arm of a saint in a case of silver, which they say was the arm of St. Peter, and which they keep with great reverence. In this church is also the tomb of Despina Caton (Khatun), the daughter of the King of Trebizond named Caloianni, who is buried under a portico near the door of the church in the earth, and above the tomb is a thing like a box one cubit high and one wide and about three in length, built of bricks and earth.”

This Venetian merchant, spending time in the city on his way to Tabriz, conveyed the awe and admiration inspired in him by the Church of St. (Virgin) Mary.

“There is also a church of St. John, beautifully built, and several others of great beauty and splendour; and while I remember, I must not pass over one of them named the church of St. Mary, the account of which will interest my readers. It is a large edifice, with sixty altars, as one sees before chapels; the interior is built up with vaults, and the vaults are supported by more than three hundred columns. There are also vaults above vaults, equally supported by columns; and, as far as I could judge, this church was never covered in, in the middle, as taking into consideration the mode of its erection, and, above all, the sacred christening font, which I saw was in the open air. This baptismal font is situated in the middle of the church, and is of fine alabaster, made like an immense mastebe, carved inside with various designs and most splendidly worked. It is covered by a magnificent block of the finest marble, supported by six columns of marble as clear as crystal, and these columns also are worked with fine and gorgeous carvings, while the whole church is inlaid with marble.

Nowadays, the eastern part of this church has been made a mosque, while the other part is in the same state it always has been, as it was the convent where the priests lived; in it there is a wonderful fountain of water, as clear as crystal. This church is so nobly built that it appears like a paradise, so rich is it in fine and splendid marbles, having columns upon columns, like the palace of St. Mark at Venice. There is also a campanile with bells, and in many other churches there are steeples without bells.”

Diyarbakır’s water sources and affinity with water impressed all visitors of the city alike, no matter the purpose of their visit. The anonymous Venetian merchant too could not but touch upon the Tigris.

“This city abounds in water, as springs rise in many places; and it is partly on a plain and partly on a mountain — in the midst of a great plain, round which many fresh-water springs gush forth. It has six gates, well-guarded by corporals and soldiers; the corporal of every gate has ten, twelve, or twenty men under him, and by every gate there is a large clear fountain.

Among the other rivers flowing through this city is one from the East named the Set (Shatt/Tigris) which, in the spring, rises wonderfully and flows rapidly towards Asanchif (Hasan Keyf) and Gizire (Jezireh), in Bagadet (Baghdad) entering the river Euphrates, and the two then fall into the Persian Gulf.”

Text: Dr. Yusuf Baluken

Translation: Feride Eralp