Chilean poet and writer Pablo Neruda’s poem ‘The Fugitive’ juxtaposes, in a single sprout, wheat, which influenced the direction of human history, and the peoples of the world who face inequalities brought on by that same history; his lines of poetry are beyond time and space. Diyarbakır has a past that allows one to speak from both viewpoints.

Lands where ten thousand years ago, the transition from a hunter-gatherer life style to a sedentary life style took place, and where seeds of wild wheat were cultivated… It is no surprise that wheat is a crop that has not lost its significance for thousands of years in Diyarbakır and its region; and that the economic relationships it has created continue to orient social structure. The failure to transform this into economic power despite the potential for production, and the economic underdevelopment of the region are outcomes of historical process and political choices.

From archaeological remains to agricultural statistics, from history to geography, and from the cellar to the kitchen we follow the traces of wheat.

In Diyarbakır, at whichever period or whichever aspect of the city’s history we look at, we come up against wheat. In archaeological layers… In mythology, in narratives of oral history; in fairy tales, folk songs, folk dances, handcrafts… In traditional manufacturing and in the business life; in the city’s relationship with the world… In bureaucratic correspondence with the capital, and other capitals… In tax and customs registries… In border disputes, wars, murders; in court records, newspaper articles… In names of neighbourhoods, like “Ofis”; in the memory of spaces… In bread, çörek [tea cakes]; religious holidays and feasts… In the gastronomic habits of the city…

Dr. Mehmet Atlı, Researcher, Writer

Wheat farming has a history of around ten thousand years in Anatolia, and constitutes one of the most important factors in the transition of hunter-gatherer communities to sedentary life, in the consolidation and proliferation of sedentary communities and ultimately, in the transformation of small settlements into cities.

Recent archaeobotanical research reveals that agriculture in what is modern-day Turkey first began in the area known as the Fertile Crescent, which includes Diyarbakır. The oldest agricultural products are Einkorn wheat, Emmer wheat, barley, lentils, peas and flax. Modern DNA fingerprinting studies reveal that Einkorn wheat (Aegilops monococcum L.) was cultivated for the first time approximately ten thousand years ago in an area close to Karacadağ, Diyarbakır.

In addition to the impact of wheat on the history of civilisation, human civilisation also influenced the evolution of wheat. In the beginning, Wild Siyez (Einkorn, Triticum boeticum) and Wild Gernik (Emmer, T. dicoccoides) were gathered from nature, but then, these two wild varieties evolved into the primitive forms of Siyez (T. monococcum) and Gernik (T. dicoccon) as planted by human beings. These primitive forms had larger grains than the wild forms, had spelt, and the wheat ears were less fragile, thus they grew more widely. We know that the cultivation of these two primitive forms from wild life took place in the Gaziantep-Şanlıurfa-Diyarbakır triangle.

Research on the genetic origins of wheat in Turkey and work to develop local varieties began in the first quarter of the 20th century. Mirza Gökgöl recorded more than eighteen thousand different types and 256 new wheat varieties across Turkey in 1935. Some of the wheat varieties Gökgöl recorded in Diyarbakır in 1935 are: Abuzer, Beyaz, Devedişi, Geore, Humrik, İskenderi, Karakılçık, Kırmızı, Kırmızı Beyaz, Kışlık Büyükbaş, Komoy, Memeli, Pırçıklı Sorgül, Ruto/Köse, Sorgül, Yazlık, Yazlık Beyaz, Yazlık Kırmızı, Yusufi.

Source: WWF-Turkey, Wheat Atlas of Turkey, 2016.

Diyarbakır has different geological and geographical characteristics since it is located in the mountain-to-plain transition area of Northern Mesopotamia; and with countless endemic plants it is “home” to many crops, including pulses like chickpeas, lentils and peas, grains like wheat, barley and oat, and grapes, almonds and peanuts, all indispensable ingredients in kitchens today. It is still possible, in the Karacadağ area, to find wild varieties of grains first cultivated thousands of years ago.

When around 11,700 years ago, with the onset of the Holocene Epoch, the climate became warmer and earth was covered in a different flora, human beings began to enrich their plant-based food chain by trial and error. Wild cereals are, in fact, not too attractive on first appearance. However, their grains can both be consumed fresh, dried to be stored, and made into flour by grinding to create different types of use for food consumption, and all these factors rendered grains more attractive for human beings.

We have findings that indicate different implementations in different geographical regions of the Near East. Carbonized plant remains and stone mortars have reached the present day from the Natuf settlements, the dominant culture of the Eastern Mediterranean region, dated to 14,900-11,700 years ago. Mortars and pestles, basalt ground stones, mano stones discovered in excavations in Diyarbakır and its environs and traces revealing that over time they became indispensable objects of the settlements, show the importance of grains, and especially wheat in nutrition.

Prof. Dr. Aslı Özdoğan

Dated to 11,960 to 8.300 years ago, Çayönü Tepesi, a settlement in the Ergani Plain with layers from the Aceramic Neolithic Period, provides many important findings regarding the cultivation and preparation for farming of wild wheat, and the importance of wheat in the transition to sedentary life.

Çayönü has six different phases of development that are parallel to fundamental changes in its architecture and extend from hunting to animal husbandry, and from gathering to production. These phases reflect stone tool technology, intense jewellery production, copperworking and the diversification of animal- and plant-based materials in nutrition. Analyses of plant remains reveal that pulses never lost their significance as a food source from the first phase of settlement in Çayönü to the present day. As sedentary life developed, Emmer (Triticum diccoccoides) and Einkorn (Triticum boeoticum) entered the “kitchen” towards the end of the second phase, the Grid-Planned Structures Phase. During this period, consumption of Einkorn (siyez) wheat increased. From the Channelled Buildings Phase that followed, wild Emmer wheat was gathered systematically. From the fourth phase known as the Cell-Planned Buildings Phase, we have today discovered many stone hoes, smooth ground stones and mano stones, sickles made of staghorn and “V” shaped tools made of shoulder bones that could be described as the forebears of wooden sickles. Burned piles of wheat in the lower, cellar-like floors of two buildings reveal not only that consumption had increased, but that the conscious storing of wheat had also begun.

By the end of the Cell-Planned Buildings Phase, Emmer wheat had been cultivated, and was being farmed. However, in the period that followed, the Large Room Building Phase that featured simpler buildings, it is known that there was a break in agriculture, because of frequent flooding, and animal husbandry once again became the dominant occupation.

Aslı Özdoğan

For many centuries, Silvan was Diyarbekir’s “wheat granary”. In the early modern period, Silvan distributed its grain crop surplus, including wheat, to less fortunate areas. This also helped alleviate the impact of frequent famines in the mountainous areas of the region. On the other hand, this surplus wheat was frequently allocated to the requirements of the Ottoman army and religious buildings.

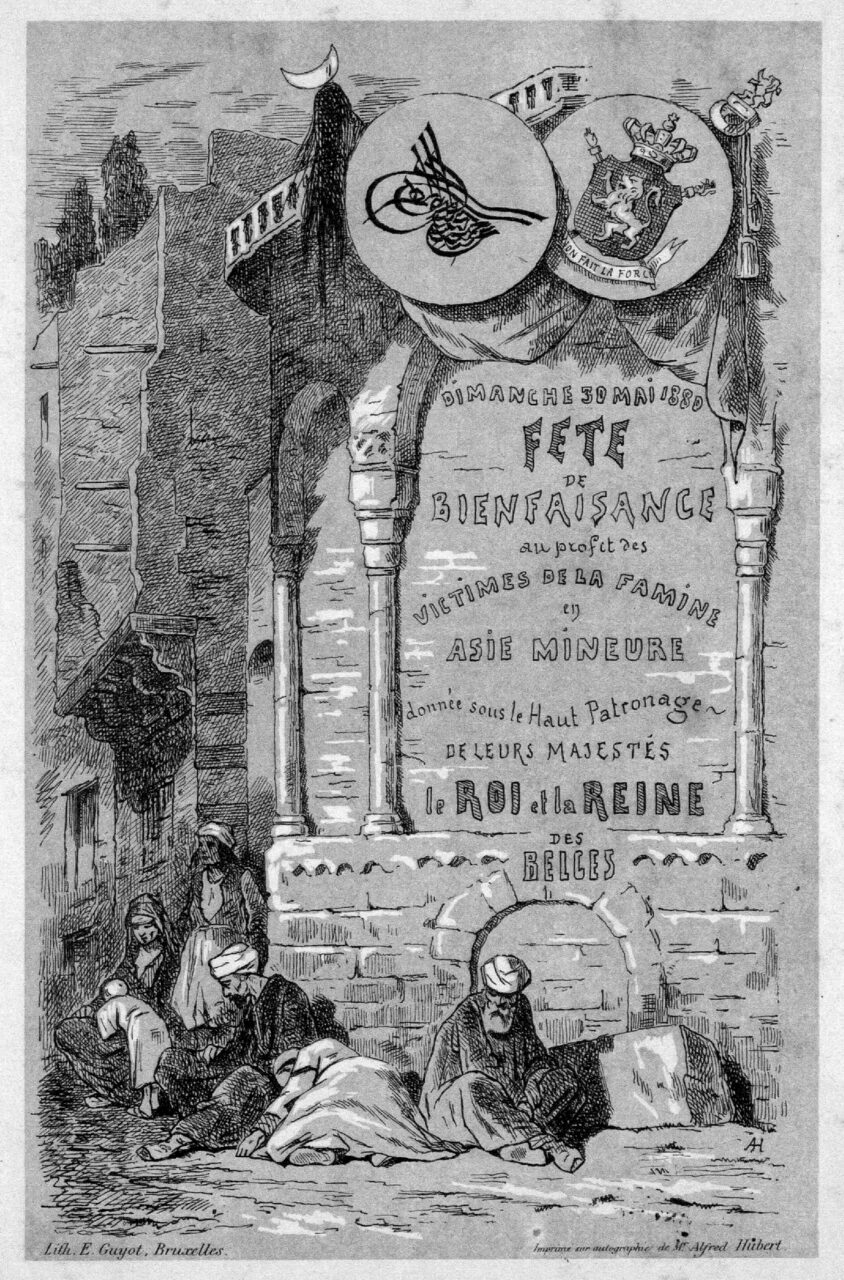

An English traveller who toured the region in the 1830s reports that in the plains of Diyarbekir, wheat yielded sixteen-fold. Although it was a crop that grew so abundantly, the famine that began with the added impact of 93 Harbi, or the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878, the drought that followed it in 1879 and the tough winter of 1880, did result in tens of thousands of people losing their life in Diyarbakır and its environs.

The first quarter of the 19th century witnessed the elimination of the mir and wars and massacres in its last quarter greatly impeded wheat production, however despite all such factors, the place of agriculture and wheat in Diyarbakır’s production volume was indisputable. Agricultural statistics compiled by the Ottoman State reveal the importance of cereal production, as 81% of farmland was allocated to this, and it formed 45,5% of the total agricultural production of the city.

Dr. Uğur Bayraktar, Historian

“Before the misery of war lifted, we faced new and greater disasters. The people are devastated because of a great famine; the price of bread is at least sixteen-times higher than normal. Everything that could replace bread is also very expensive. And compared to Mosul, Mardin, Siirt, Van and Bayezid, it is still cheap here. There are more than four thousand people who depend on aid in this city; the streets are full of beggars and many of them perish in hunger. Although the benevolent hand of the English people does extend to these unfortunate people, the famine is at such a dreadful scale that no aid can save the country from this inevitable disaster. The severity of the harsh winter has increased the suffering of the poor tenfold. May God help us all.”

This letter written by the spiritual leader of the Diyarbakır Protestant Armenian community was published in the New York Evangelist magazine on 27 May 1880. This is an important document of the famine that began in 1880 and ultimately led to the death of at least ten thousand people. Around the same time, on the order of the sultan, rain prayers were performed across the region.

When the impact of the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878, drought and a tough winter combined with the continuing economic bottleneck and an administrative structure that prevented the just distribution of the wheat in stock, hundreds of thousands of people were condemned to hunger. The majority of those who died where Kurds from nomadic tribes that made their living through animal husbandry. The arduous conditions also led to incidents of violence and pillaging. Pillaging gangs targeted Armenian, Turkish, Kurdish, Assyrian and Syriac villages and worsened the already terrible conditions of the famine. While certain merchants were busy with stockpiling and price speculation, many ovens made bread with polluted or spoiled flour and tried to sell it at exorbitant prices.

On 14 June 1880, a bread riot took place, it was initiated, according to Diyarbakır Governor İzzet Pasha, by “hundred to hundred-and-fifty fools”. At first, upon the call of a group made up of “Muslim and Christian subjects”, five to six hundred people gathered to wire a telegraph to the Sublime Porte. Over the next days, the disquiet grew among the people and riots began. The first target was those who profited from the conditions. Additional military forces arrived in Diyarbakır, flour was also brought in from other cities, and bread prices dropped a little.

The incident indicated a structural problem that went beyond a shortage of wheat, and it is important in that it sheds light on the region’s history, generally discussed from an ethnic perspective, in terms of socio-economic problems such as famine and impoverishment.

Source: Özge Ertem, “Önce ekmekler bozuldu: 1880 Diyarbakır ekmek isyanı [First the bread spoilt: The 1880 Diyarbakır bread riot]”, Toplumsal Tarih, 109, 2010, p. 74-79.

Özge Ertem, “‘Fiyatı Âlidir!’: Diyarbakır’da Kıtlık, Yokluk ve Şiddet” [The Price is High! Scarcity, Poverty and Violence in Diyarbakır]”, Diyarbakır Tebliğleri, Hrant Dink Vakfı Yayınları, 2013, p. 73-79.

Production of grains, and especially wheat, did not only hold an important place in agricultural production but also was a significant factor in land division, and inevitably, in the social structure of Diyarbekir. In the 19th century, there was a period when the large swathes of land in the control of mir were broken up when the state sent them into exile, and small-scale production in the hands of peasants came to the fore. However, this did not last long. The Ottoman Land Code of 1858 meant that lands in Diyarbekir and local districts had passed into the hands of notables. However, the process of “seizure” of abandoned possessions and properties (emvâl-i metrûke) that began with 1894 Sasun Massacre and ended with the 1915 Genocide meant that all lands passed into the hands of the politically powerful bey and agha. These lands that produced wheat had also become the source of the social exploitation in the region.

Governments from the early years of the Republic until the 1960s produced discourses regarding the elimination of this “structure”, however, they stood clear of developing policies like land reform. On the other hand, wheat production was stimulated along with mechanization in agriculture. To whom those machines were given, and land ownership in agricultural production including wheat, continue to be valid factors in the economic underdevelopment of the region to this day.

Uğur Bayraktar

Black Wound

There they lie across two columns of the front page, two naked babies,

There on two columns of the front page a handful of skin and bones,

Their hands pierced, exploded,

One from Diyarbakır, the other from Ergani,

Their arms, their legs, all crabbed and crooked,

their heads so huge,

their mouths open with a terrible scream,

two tiny frogs flattened with a rock on the front page.

Two tiny frogs

my two babies with black wounds,

Who knows how many thousands of you every year,

come and go without even drinking your fill of bitter water…

And Mr. Undersecretary speaks:

(May the black wound visit upon him too)

“No cause for alarm” he says.

Nazım Hikmet wrote this poem (“On Newspaper Photographs”) dated 3 August 1959, after reading Musa Anter’s articles on the “black wound” in the İleri Yurd newspaper. The detection of fungicides in wheat seedlings distributed by the state in 1958 and the deaths this caused would later lead to Anter writing his play titled “Birîna Reş” (“Kara Yara/Black Wound”). “I wrote this work when I was incarcerated in cell no.38 at the Military Academy in Istanbul in 1959,” he writes in the introduction.

Mehmed Uzun wrote a preface for the play that was first published in 1965, and he states, allowing himself a degree of error, that this play is, quite probably, the first Kurdish language work published in Turkey in the post-Republican period, emphasizing the importance of the work at a period “when the smoke of a never-ending fire continues to rise from the lands where the Kurds live”. The “black wound” caused by wheat containing chemical residue, according to Uzun, symbolizes two other “wounds” for Kurds: Poverty and ignorance.

Source: Musa Anter, Birîna Reş / Kara Yara [Black Wound], Avesta Yayınları, 1999.

“‘Birîna Reş’ was written against the antagonistic slogans, symbolizing a false partisanship, of the DP (Democrat Party) imposed upon the Kurds in the 1950s: ‘The Kurd is no good, the Kurd is not literate!’ they said. The play was a reaction against all the misery, scorn and hatred against the Kurds. In order to understand my view, it is necessary to read and understand the play. My play also contained the image of ‘DP’s Kurds’ of that period. All across the south-eastern region, wheat is planted in October. But in April, hundreds of thousands of tonnes of wheat laced with the most vicious pesticides was distributed to the DP-supporting aghas and sheikhs in the region. And of course, these hundreds of thousands of tonnes of wheat was sold by the aghas, or landlords, to the impoverished Kurdish people at a price cheaper than barley. The uneducated Kurdish people ground and made flour of this wheat, and made bread from that wheat. This wheat, that should have been used only for pest control, was consciously being used to destroy the Kurdish people. In short time, its results became apparent, with children the worse hit. The wound that this fungicide caused in the bodies of children was called ‘birîna reş’ among the people, which means ‘black wound’. I used to work at the İleri Yurd newspaper in Diyarbekir at that time. I underlined this reality many times. But the monsters did not give up on carrying out their plans to deplete Kurdistan. It was around that time that I had made a tour of the environs of Diyarbekir and went to Çüngüş, Dicle, Hazro, Lice, Hilvan, Çınar and Bismil. I stopped by village clinics in the districts, many of them without a doctor. Here, I saw hundreds of children, covered in wounds, resembling infant monkeys. The faces of all the children had turned black, and were covered in hairs a hand-span-long. Their faces and bodies were covered in wounds that did not heal, and pieces of flesh had torn off various part of their bodies. A great majority of the children were dying. This happened in 1958. If a statistical account could be drawn up today, I believe it would show that there are very few Kurds born on that year, and up to three or five years before it.

This had left a deep impression on me and influenced me to write the play. I also frequently described this episode in my articles in the İleri Yurd newspaper. However, the Ministry of Health tried to respond to my articles through the false reports it produced, claiming that the disease was caused by wheat. There was a strong reaction. So much so that Nazım Hikmet supported me from Moscow and wrote a poem titled ‘Minister of Health May the Black Wound visit upon Him’”.

Musa Anter, Hatıralarım [My Memoirs], Avesta Yayınları, 2000.

The abundance of wheat meant that in Diyarbakır and its environs, it was used widely, and it brought great variety to kitchens. Cracked wheat was always preferred both because of its superior taste and the consistence it added to dishes.

Although its cuisine is not generally dominated by flour, bread is culturally accepted as a holy food. Flour is uses most in bread- and börek-making. Bread is bakes in a variety of different ways, with leavened or unleavened dough, in the tandır [floor furnace], or on sac [heated metal sheet] or stone.

Diets in the city centre and in rural areas differ. This is not only about the ingredients used, the preparation and cooking methods in rural areas may be influenced by the fact that women actually work in the fields. More cereals are used in rural areas. Dough prepared for bread baking is turned into a meal course by adding various herbs, cheese, çökelek [a type of fermented fresh cheese] or meat. There are also types of pastry made with unleavened dough. Vegetables are also grilled on the tandır or stove lit to bake bread.

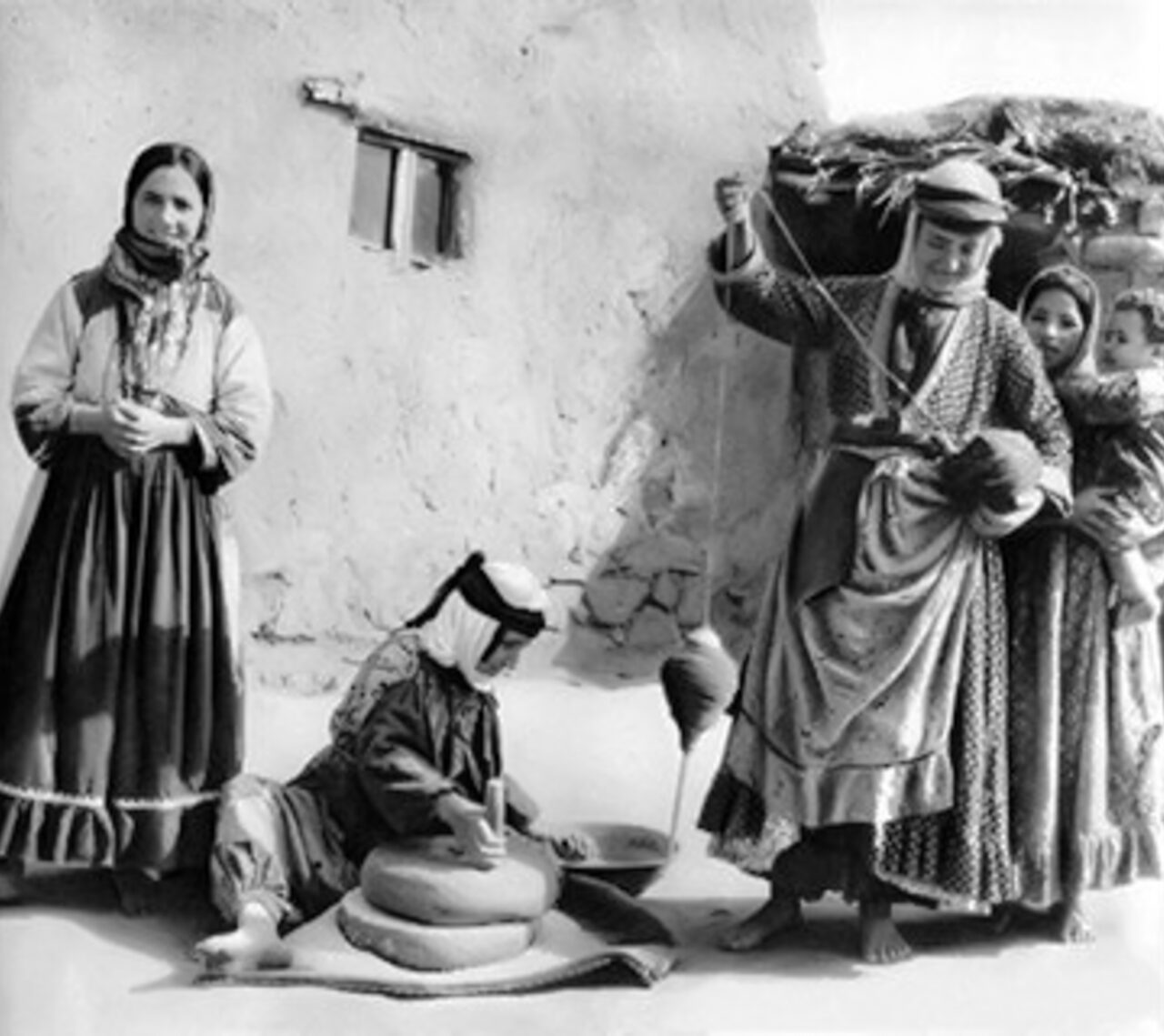

In the past, bulghur, dövme wheat or lentils used to be milled in hand-mills called “destar”. Later on, this was replaced by larger, mobile mills the arrival in the neighbourhood of which would be announced by chanting, “Bulghur to be milled, bulgur to be milled”. The milling would often take place in courtyards, and the milled bulgur would be sieved through the large-holed colander. The kernels left on top would be milled again and passed through three separate sieves, “kibe kudurluk”,¹ pilavlık [for pilaff] and köftelik [for meatballs]. This tradition continues to this day in rural areas.

Source: Filiz Parlak, Meftune, 2002.

¹ The largest form of bulghur left on the very top after it is sieved once it has been milled. Kibe is used as filling in the dish called mumbar, and depending on its size, is divided into three categories: pilavlık [for pilaff], cücük [for tabbouleh] and içli köftelik [for filled meatballs].

“Like in all parts of Anatolia, in my hometown, Diyarbakır, too, and at our home, bread was the staple food. We had been taught that bread, in all languages and all faiths, was the holiest among all foods. Because whether you called it ‘hats’ in Armenian, ‘nan’ in Kurdish, or ‘khıbz’ in Syriac or Arabic, bread, after all, is the blessing, not of human beings who make it, but of God, who gave life to wheat.

(…) Bread was the source of abundance in our cellar. Was there anything my skilful mother couldn’t do as long as there was flour in the cellar? First and foremost, she would bake the bread we ate at every course. The stone bread she baked on the piece of volcanic rock from Karacadağ, which we ate by spreading sugar or the molasses kept in the glazed green earthenware jar in our cellar on slices of it; ‘zingilik’ which she made by frying in oil leavened dough with a liquid consistence; lavash, which she kneaded with plenty of oil and we cooked by sending it off to the oven of the neighbourhood bakery and the gözleme known as ‘patila’, prepared with a great variety of fillings… Bread was so important and valuable that for my grandmothers the kitchen was not the place where the cooking is done, but the place where the bread is baked, or ‘tennurdun’, the place of the tandır.

When autumn came, my father would go to Diyarbakır’s Buğday Pazarı, the wheat market, and buy wheat sold in hemp sacks. Wheat that would last us through the winter would be lined up in sacks in the covered iwan of our church, the courtyard of which our houses faced. The sack of wheat would be opened with my mother’s wish, ‘Kherov, parov, sağutunov, urakh srdov’, meaning, ‘with blessing, goodness, health and joy’, and the prayers and good wishes of our neighbours would accompany her.”

Silva Özyerli, Amida’nın Sofrası: Yemekli Diyarbakır Tarihi [Amida’s Dinner Table: A History of Diyarbakır in Food], Aras Yayıncılık, 2019, p.11.

Stone Bread

½ kg whole wheat flour • ⅓ packet fresh yeast (approx 15 gr.)

1-1,5 tbsp clarified butter • 1 tsp sugar and salt

For the sauce: 1 water glass of küncü (golden sesame, simit sesame)

1 tea glass of molasses • 1 glass of water

Roast the sesame at a low heat. Once the sesame begins to crackle, turn off the heat but continue to stir for a while longer. Chop the sesame you have roasted in the food chopper but not too small. Add molasses and water to the sesame you have ground, boil the mixture into a dense sauce.

Melt the butter, wait. Mix the yeast, sugar, salt and approximately 4-4,5 glasses of warm water well, dissolve the yeast. Then slowly and gradually add a little flour and whisk. You can use a mixer but I prefer to do it by opening my fingers and airing out the dough as I whisk it, as we used to do in the old days. And of course, “Don’t forget that the hand adds its own to the taste”. The dough should be of a liquid consistency like crepe dough. Cover the dough you have kneaded and wait for it to leaven for 1-2 hours until you see small air bubbles on the surface of the dough.

Give the leavened dough a stir and let it air out.

Place a crepe pan on the fire and heat it up well. Once the pan reaches the required temperature pour 1 ladle of dough into the pan (may vary according to pan size) and tilt the pan to the right and left to make sure the dough spreads evenly. When the top of the dough begins to bubble, gently place the spatula beneath it, turn it along the axis of and rescue the dough from the pan and flip it. When both sides are cooked, transfer the stone bread onto a plate and grease it with a brush (this used to be done with a clean piece of cloth in the past). Place the bread you have cooked on top of each other, and after each one is done, grease them and place them to the side.

You can serve the stone bread and its sauce separately (so that the bread can be dipped in the sauce).

Note: Stone bread was the most valuable sweet bread of religious fasting days, when it was then made with olive oil. It is called stone bread because its dough is cooked on a real piece of rock. People would ask to borrow it from their neighbour who had this specific type of stone in their house, and carry it to their home. The stone, probably, visited more homes than its owner.

You can also serve the bread by adding plain molasses, sugar and jam.

Silva Özyerli, Amida’nın Sofrası: Yemekli Diyarbakır Tarihi [Amida’s Dinner Table: A History of Diyarbakır in Food], Aras Yayıncılık, 2019, p.195-196.

For decades now the transformation of wheat fields into built-up estate lots has continued in rural areas swallowed up by a process of urbanization that was not foreseen, not planned for development processes other than a few limited arrangements and not managed properly. It is no longer possible to speak of any meaningful wheat production in and around the city centre. Although Diyarbakır is statistically third in wheat production in Turkey, this does not correspond to a leap in the city’s general economic situation. Therefore, in the present day, just like the rasped and shredded cosmopolitanism of the city, amidst the cacophony of genetically modified seeds, the reduced number of bread varieties, arguments over gluten content and global capitalism, the “song of wheat” cannot be heard at all anymore. Perhaps it is buried in the ground, waiting to bear seeds.

Mehmet Atlı

Translation: Nazım Dikbaş

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aslı Özdoğan

• Caneva, I., Davis, M., Marcollongo, B., Özdoğan, M. ve Palmieri, A. M. (1993) “Geo-archaeology in the Northern Diyarbakır Region”, Essays on Anatolian Archaeology, Bull. of the Middle Eastern Culture Center in Japan, VII, (ed.) T. Mikasa, Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden: 161-168.

• Erim-Özdoğan, A. (2011) “Çayönü”, The Neolithic in Turkey: New Excavations & New Research, The Tigris Basin, (ed.) M. Özdoğan, N. Başgelen, P. Kuniholm, Archaeology & Art Publications, Istanbul: 185-269.

Uğur Bayraktar

• Arslan, R. (1992) Diyarbakır’da Toprakta Mülkiyet Rejimleri ve Toplumsal Değişme [Land Property Regimes and Social Change in Diyarbakır], Diyarbakır Tanıtma, Kültür ve Yardımlaşma Vakfı, Ankara.

• Beşikçi, İ. (1970) Doğu Anadolu’nun Düzeni: Sosyo-Ekonomik ve Etnik Temeller [The Order of Eastern Anatolia: Socio-Economic and Ethnic Foundations], E Yayınları, Ankara.

• Ertem, Ö. (2013) “‘Fiyatı Âlidir!’ Diyarbakır’da Kıtlık, Yokluk ve Şiddet, 1879-1901 [The Price is High! Scarcity, Poverty and Violence in Diyarbakır, 1879-1901]”, Diyarbakır ve Çevresi Toplumsal ve Ekonomik Tarihi Konferansı Tebliğleri [Papers Presented at the Conference [Papers Presented at the Conference ‘The Social and Economic History of Diyarbakır and the Region’], Hrant Dink Vakfı Yayınları, Istanbul: 73-79.

• Güran, T. (1998) 19. Yüzyıl Osmanlı Tarımı Üzerine Araştırmalar [Studies on 19th Century Ottoman Agriculture], Eren Yayıncılık, Istanbul.

• Issawi, C. (1982) An Economic History of the Middle East and North Africa, Columbia University Press, New York.

• İzmir Fuarında Diyarbakır [Diyarbakır at the İzmir Fair], Diyarbakır Ticaret ve Sanayi Odası, Diyarbakır, 1938.

• Pehlivan, Z. (2016) “Abandoned Villages in Diyarbekir Province at the End of the ‘Little Ice Age’, 1800-50”, The Ottoman East in the Nineteenth Century: Societies, Identities and Politics, (ed.) Tolga Yaşar Cora, Ali Sipahi and Dzovinar Derderian, I.B. Tauris, London and New York: 223-246.

• Üngör, U. Ü. and Polatel, M. (2011) Confiscation and Destruction: The Young Turk Seizure of Armenian Property, Continuum, London.

• Yadırgı, V. (2017) The Political Economy of the Kurds of Turkey: From the Ottoman Empire to the Turkish Republic, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.