In any attempt to chart out Diyarbakır’s history through maps, one must start with the Middle Ages. Over the years, different motives have led geographers, travellers, soldiers and political actors to map the region in various ways.

In the Middle Ages, words and expressions borrowed from Arabic such as “cuğrâfiyâ” or “ca‘râfiyâ” (i.e. “geography”), “sûretü’l-arz” (roughly, “the face/description of the earth”), “resmü’l-arz” (“the picture of the earth”), “sıfâtü’d-dünyâ” (“the appearance of the world”) and “eşkâlü’l-arz” (“the forms of the earth”) were used to refer to maps. The cartographic tradition espoused by Islamic geographers was based on Ptolemy (d. 168), whose influence would last for some centuries. Ptolemy defined geography as “a graphical, pictorial representation of the known world”.

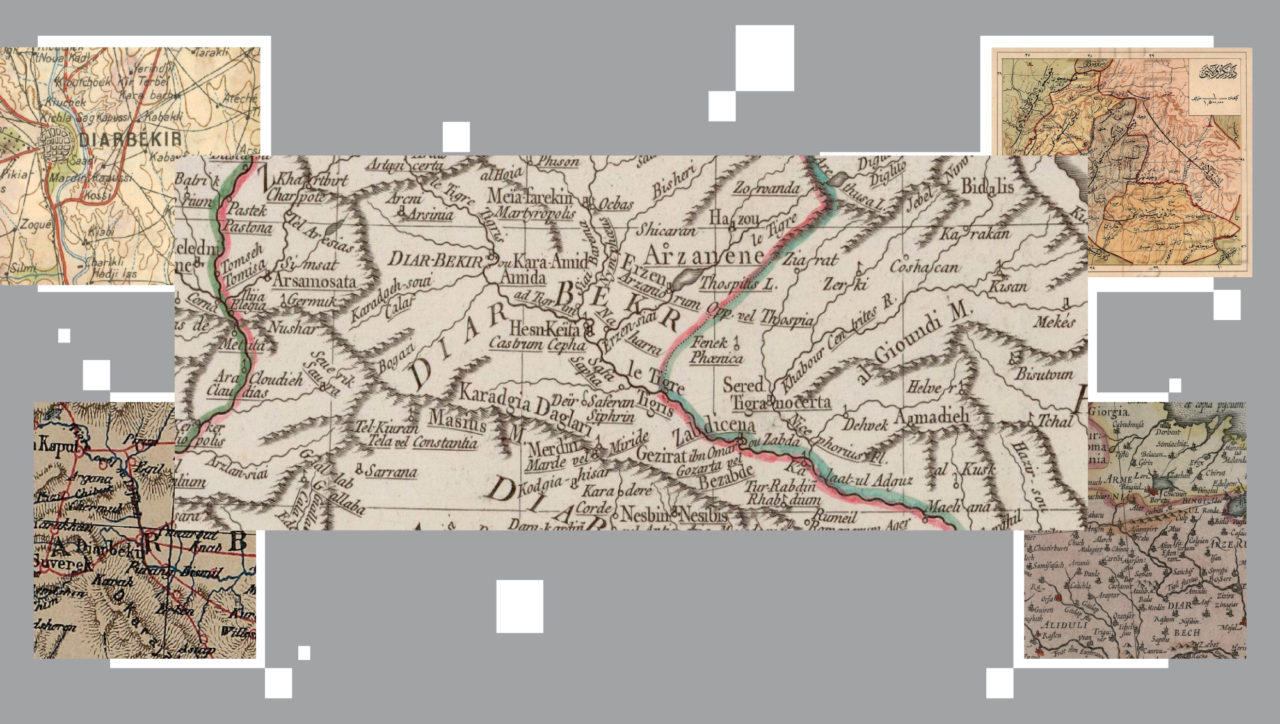

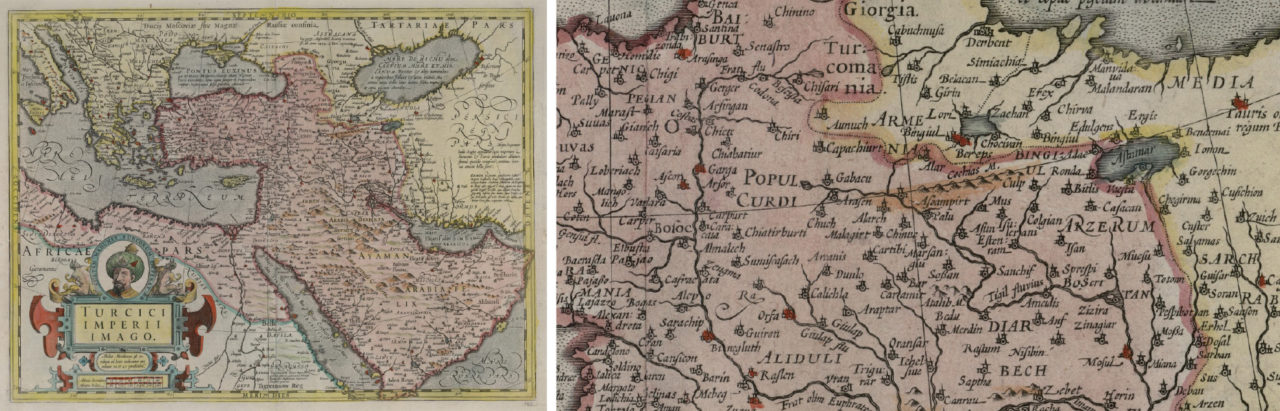

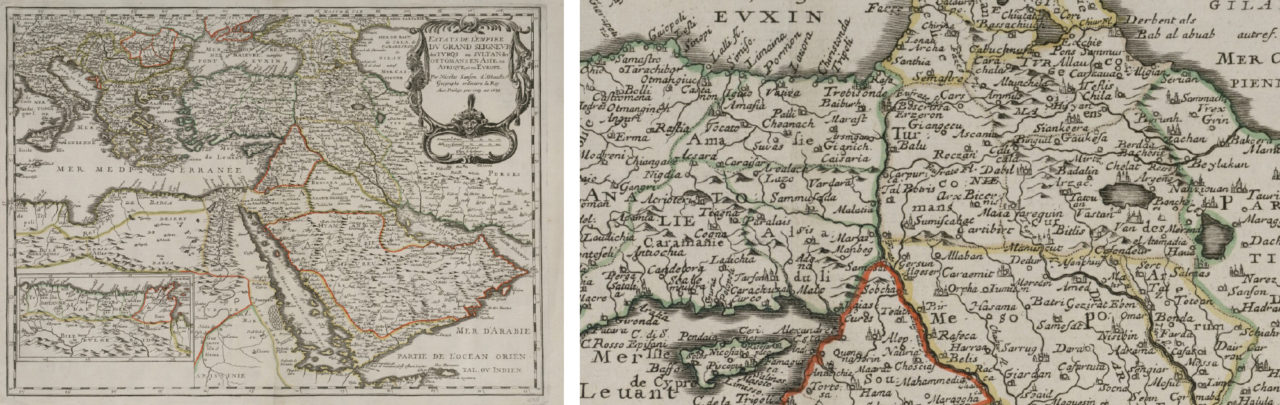

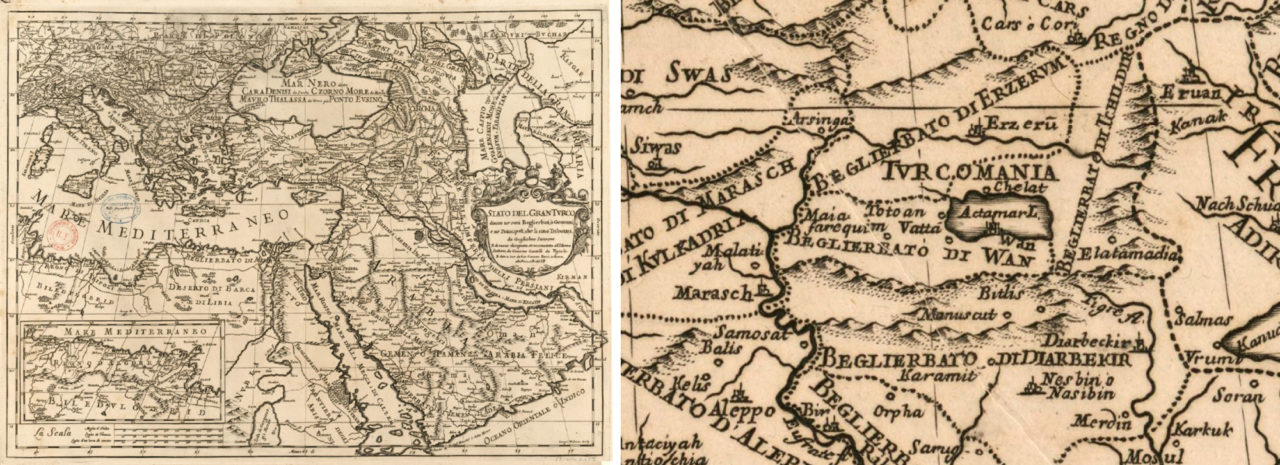

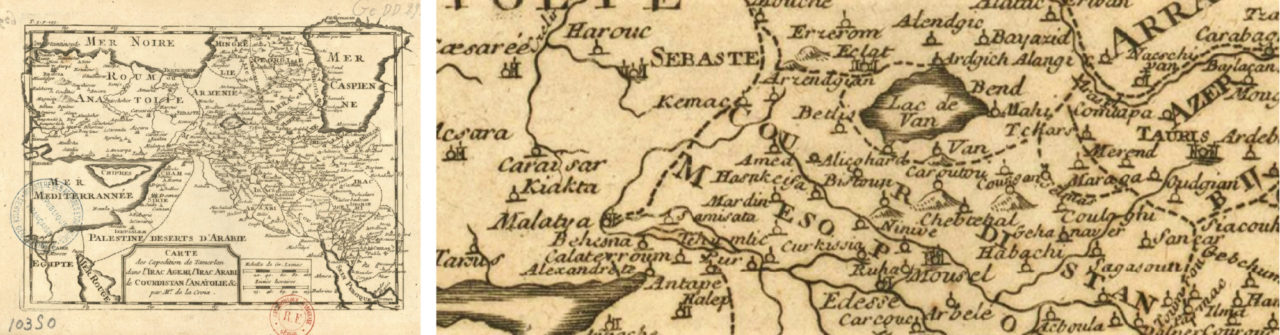

In these mostly multi-colour maps, the city has been varyingly designated as Amida, Amid, Amed, Kara (Black) Amid, and Diyarbekir in different epochs and finally as Diyarbakır in the early years of the Republic. It is particularly interesting that “Kara Amid” has ended up transliterated as “Caramit” or “Caraemit” in some maps using Latin letters, even though in actuality the city never carried such a name. This quick journey through maps also reveals the changes the city underwent as an administrative unit.

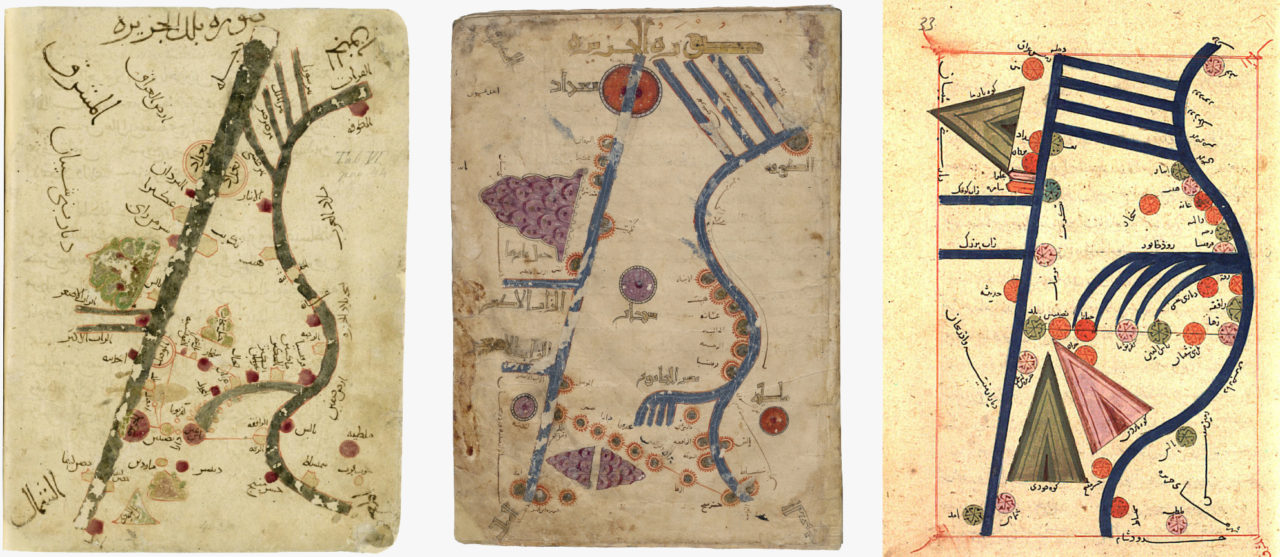

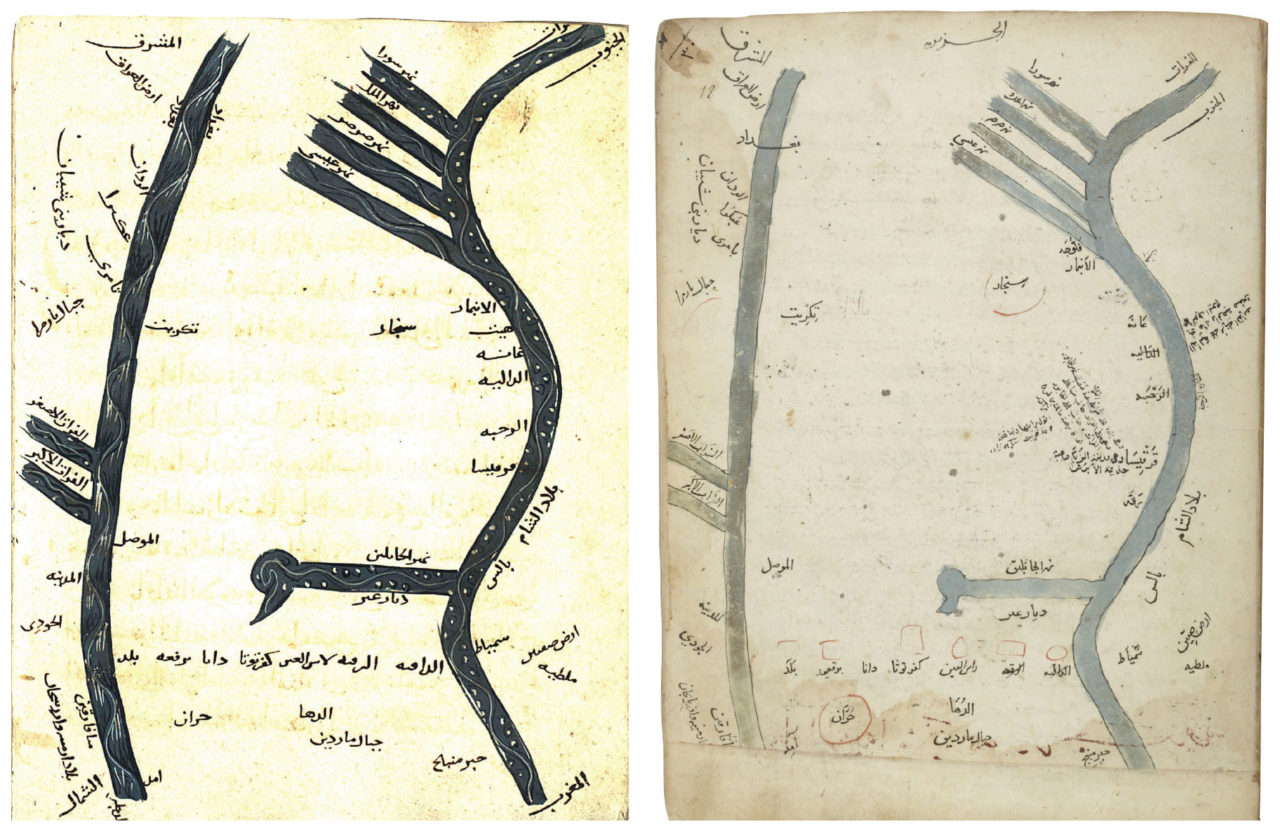

In his treatise titled “Masalik al-Mamalik” (variously translated as “Book of Roads and Kingdoms” and “Routes of the Realms”), medieval Islamic scholar of geography al-Istakhri (d. 957) provides twenty regional and one world map, where the world is depicted in circular form. The city of Diyarbakır is in the al-Jazira (i.e. Mesopotamia) section and appears as Amid. The locations of rivers, mountains and settlements have been marked.

Al-Istakhri’s contemporary and author of “Surat al-Ard” (“The Face of the Earth” or “The Book on the Shape of the Earth”), Ibn Hawqal (d. 977) produced twenty-two maps, including sea charts and a world map. In these too we encounter Amid in al-Jazira, namely Mesopotamia.

Muslim geographer al-Sharif al-Idrîsî (d.1165) owes his true fame to “Kitab nuzhat al-mushtaq fiikhtiraq al-afaq” (“The Pleasure Excursion of One Who Is Eager to Traverse the Regions of the World”), a geographic compendium he completed in 1154 under the auspices of Sicilian monarch Roger II. This manuscript, also known as the “Tabula Rogeriana” or “al-Kitab al-Rujari” (“The Book of Roger”) is arranged according to climes. He has also depicted Amid by the Tigris River in the al-Jazira (Mesopotamia) section of the book.

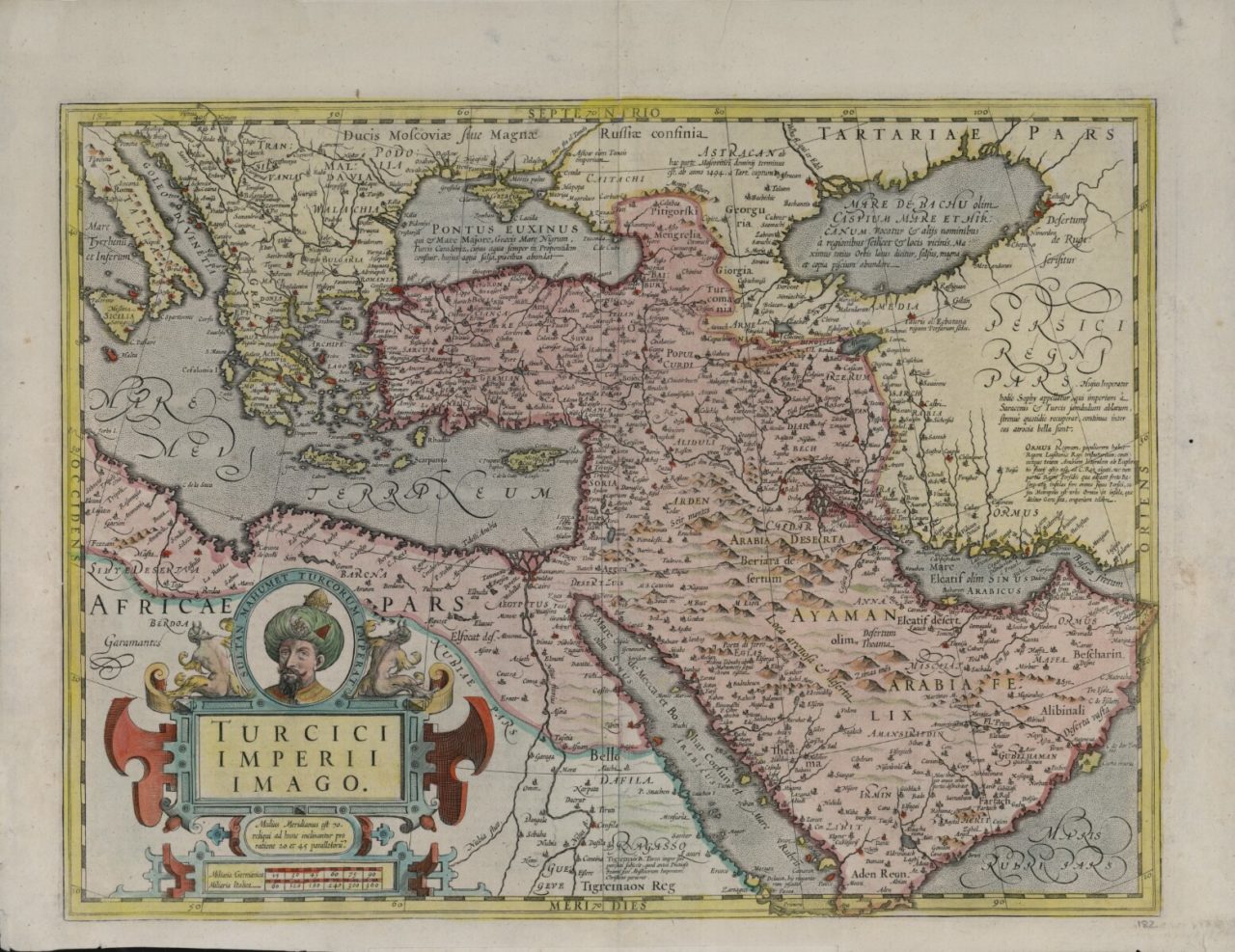

This map portraying the Ottoman Empire at the start of the 1600s is thought to have come from “Atlas sive Cosmographicae Meditationes de Fabrica Mundi et Fabricati Figura” (“Atlas or cosmographical meditations upon the creation of the universe, and the universe as created”) published by Flemish cartographer Jodocus Hondius (d. 1612) following upon the work of famed cartographer Gerardus Mercator. The figure depicted in the corner is most probably Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror. In this map, Diyarbakır’s then name Kara Amid appears inscribed as Caramit.

The 1679 edition of the map first prepared by French cartographer Nicolas Sanson (d. 1667) in the 1650s shows geological features such as rivers, deserts and mountains along with cities and towns. Coloured lines have been used to mark the borders of kingdoms. As place names are written in French, Kara Amid has this time become Caraemit.

A product of the work of French cartographer Guillaume Sanson (d. 1703) and Italian cartographer Giacomo Cantelli (d. 1695), this map was printed by Giovanni Giacomo Rossi in Rome in 1679. Here too, Karamit – i.e. Kara Amit – is shown as the capital of the Beylerbeylik (an Ottoman administrative division sometimes translated as “province” or “governorate”) of Diyarbekir.

French orientalist François Pétis de la Croix (d. 1713) came to Istanbul and İzmir in order to learn Eastern languages, carrying an assignment letter dated 1669. In 1710, he edited and published with various additions his father’s “Histoire du grand Genghizcan, premier empereur des anciens mogols et tartares” (“History of Genghizcan the Great, First Emperor of the Ancient Moguls and Tartars”). In the map prepared for this endeavour, Diyarbakır is recorded under the name of Amed and shown amongst the lands invaded by Tamerlane.

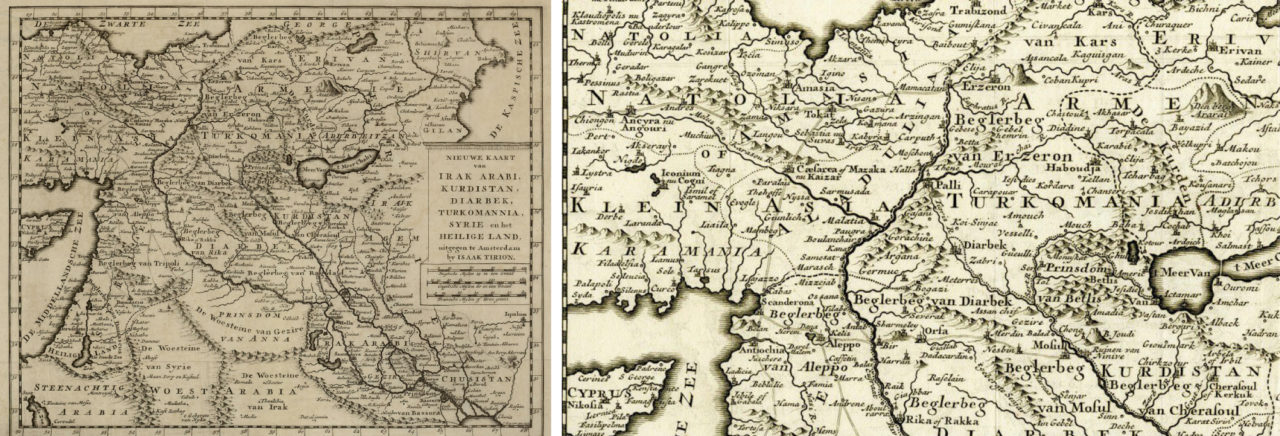

Dutch cartographer Isaak Tirion (d. 1763) prepared and published a great number of atlases and city plans. In one of these, dated 1773 and titled “Nieuwe Kaart van Irak Arabi, Kurdistan, Diarbek, Turkomannia, Syrie en het Heilige Land” (“New Map of Arab Iraq, Kurdistan, Turkmenistan, Syria and the Holy Land”) he has marked the capital of the beylerbeylik as “Diarbek”.

French geographer and cartographer Jean-Baptiste Bourguignon d’Anville (d. 1782) produced detailed atlases and maps of China, Africa and Asia. In the map he is thought to have published in 1779 named “L’Euphrate et le Tigre” (“The Euphrates and the Tigris”) after the two rivers it depicts, we encounter all three of the city’s names, Diar-bekir, Kara Amid and Amida.

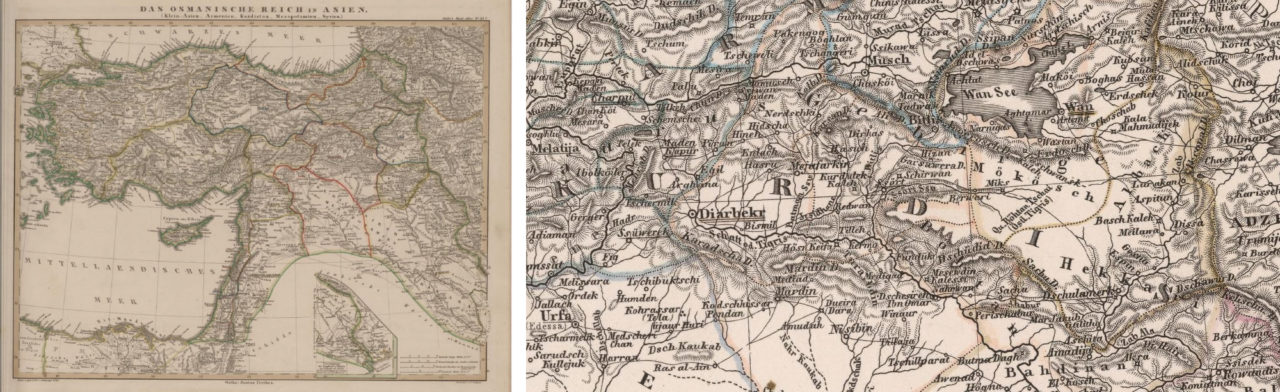

In the “Hand-Atlas über alle Theile der Erde und über das Weltgebäude” (“Handy Atlas of All Parts of the World and of the Universe”) published in 1846 in Gotha by German cartographer Adolf Stieler (d. 1836), there is a map titled “Das Osmaniche Reich in Asien” (“Ottoman Empire in Asia”). Here, the city is recorded as Diarbekr.

John George Taylor, then British consul in Diyarbekir, traveled along the eastern and western branches of the Tigris River in 1856 and kept extensive notes on the historical sites and artifacts he encountered. In an article he then wrote, the city of “Diarbekr” too has been featured with a detailed map.

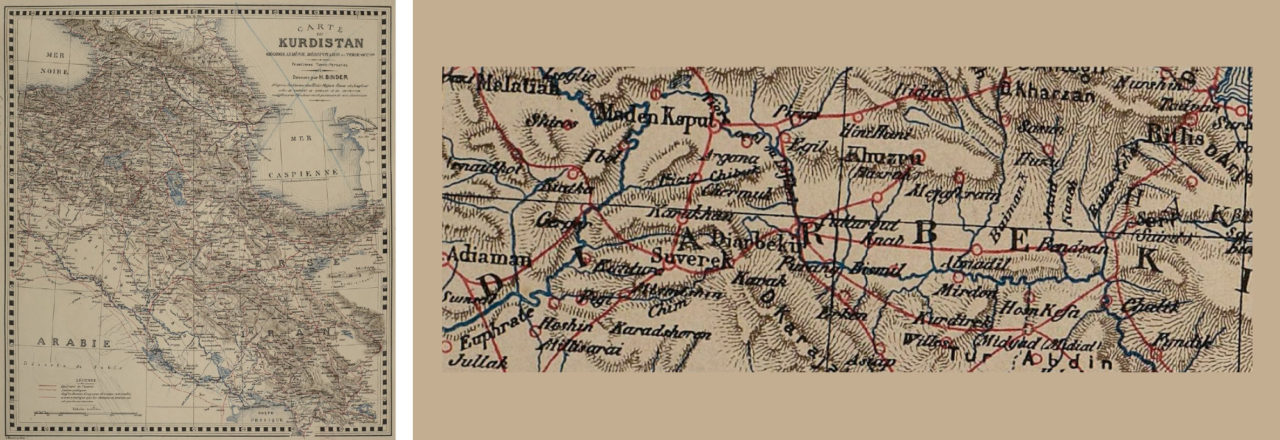

The “Carte du Kurdistan, Géorgie, Arménie, Mésopotamie et Perse Occidentale / Frontières Turco-persanes” (“Map of Kurdistan, Georgia, Armenia, Mesopotamia and Western Persia / Turkish-Persian Borders”) drawn by Henry Binder was printed in 1887. The city has been depicted under the name “Diarbekir” in this source as well.

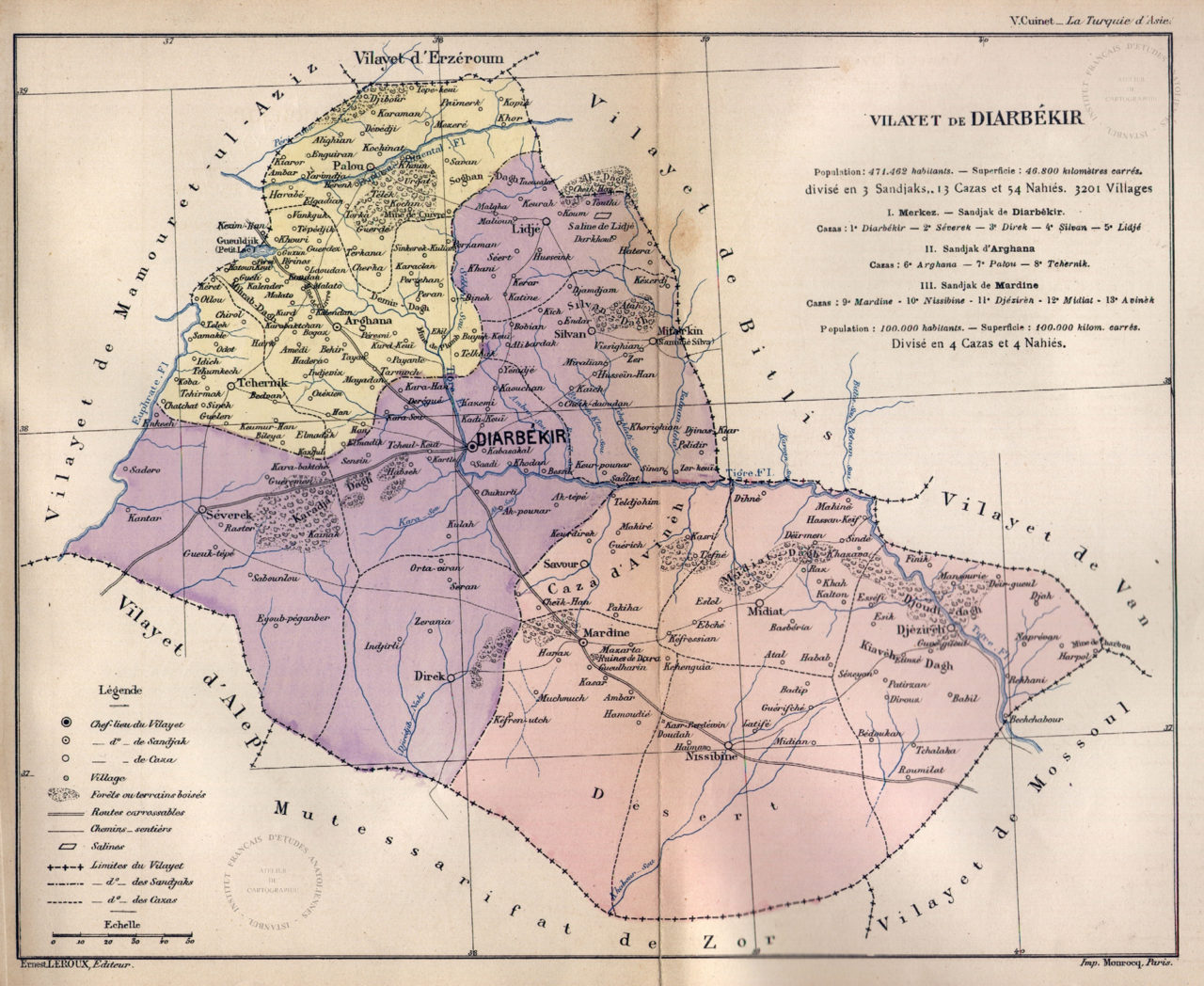

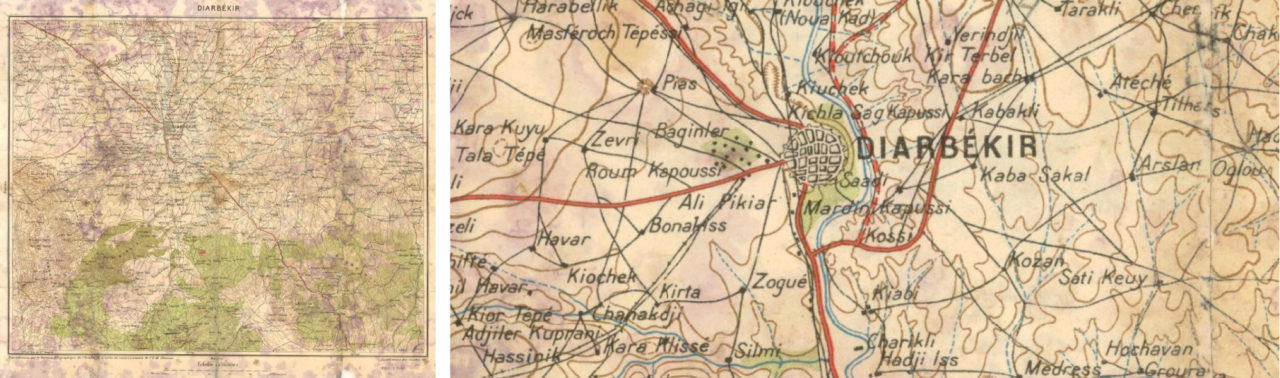

French researcher and traveller Vital Cuinet (d. 1896) was charged by the Ottoman Public Debt Administration (Düyûn-ı Umumiye) with travelling through the Empire’s towns and listing their economic, social and cultural inventory. Vital Cuinet’s study dated 1891 was then published as a book a year later in Paris under the name “La Turquie d’Asie: Géographie Administrative” (“Turkey in Asia: Administrative Geography”). As part of his inventory, Cuinet has also prepared a detailed, special map of Diyarbakır, which he provides in the section on the province.

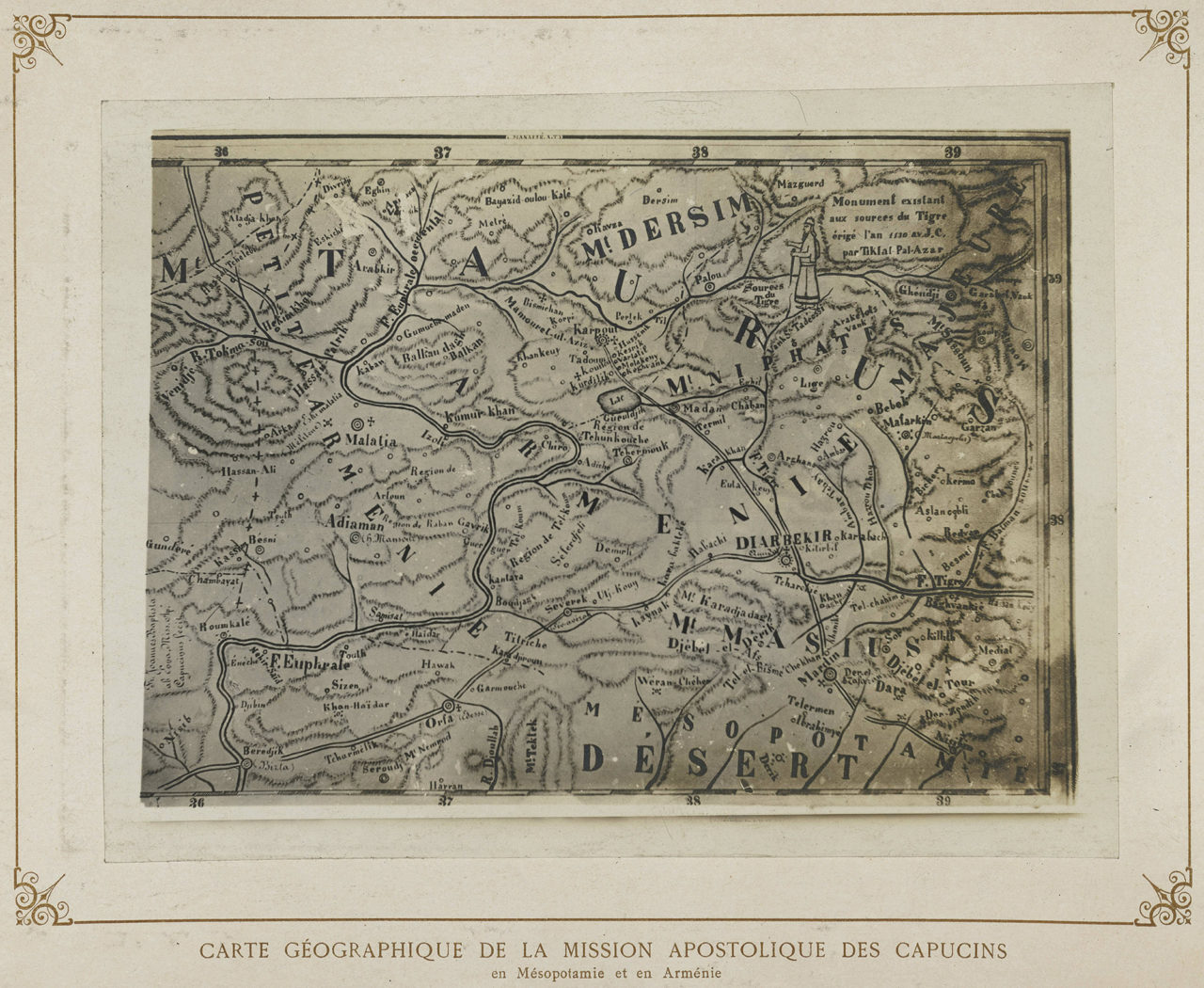

The album titled “Album de la Mission de Mésopotamie et d’Arménie confiée aux Frères-Mineurs Capucins de la Province de Lyon” (“Album of the Mission to Mesopotamia and Armenia entrusted to the Friars Minor Capuchin of the Province of Lyon”) prepared by Friar Raphaël de Ninive and published in Paris in 1904 contains many rare and precious photographs documenting everyday life. In the album, a map titled “Carte géographique de la mission apostolique des capucins en Mésopotamie et en Arménie” (“Geographic Map of the Capuchin Apostolic Mission in Mesopotamia and Armenia”) portrays Christian settlements in Diyarbakır and its environs.

One of the Porte’s (Babıali, i.e. Sublime Porte – used to signify the government of the Ottoman Empire) first publishers, Tüccarzâde İbrahim Hilmi (Çığıraçan – the “trailblazer” or “epoch-maker”) printed an atlas portraying the political and administrative divisions of all provinces of the Ottoman State in 1907. In this work titled “Memâlik-i Osmâniyye Cep Atlası” (“Pocket Atlas of the Ottoman Lands”), Diyarbekir has its own map just like every other Vilayet (Province).

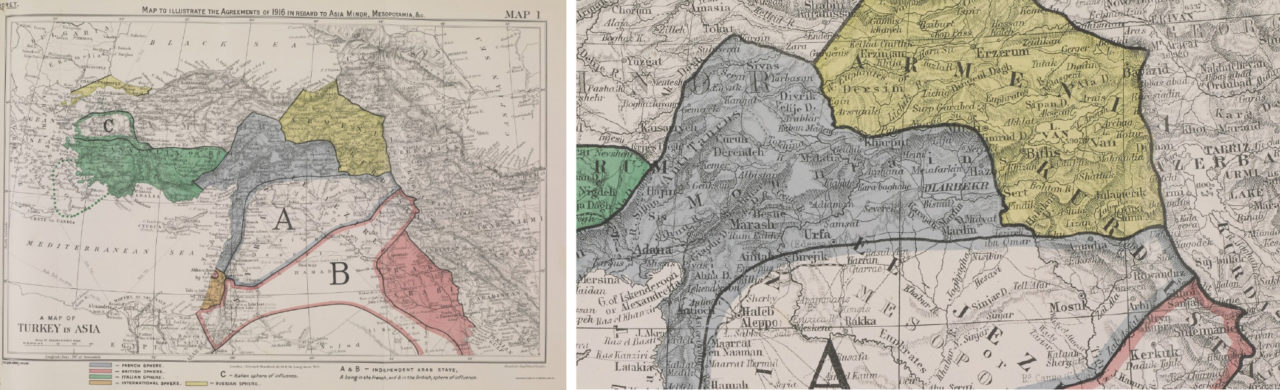

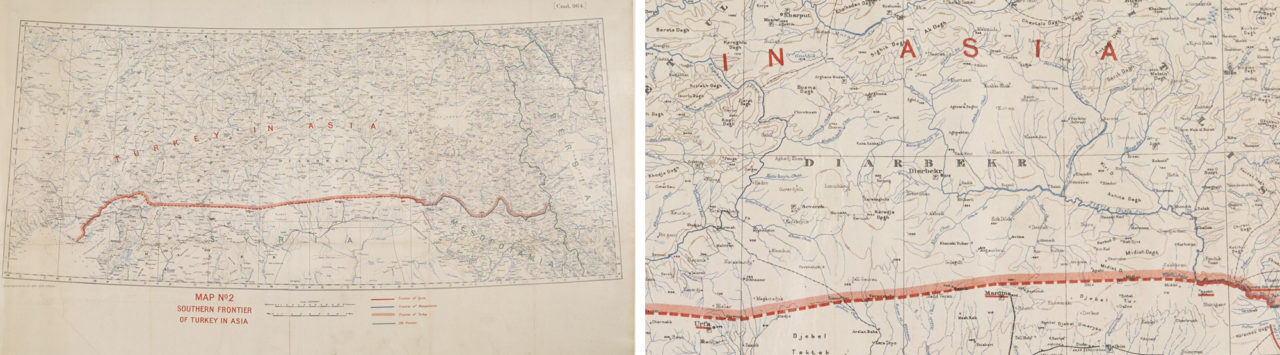

During World War 1, the Allied Powers had prepared maps to determine the fronts on which they would fight the Ottoman Empire. Here, Diyarbakır is shown within the French field of activity.

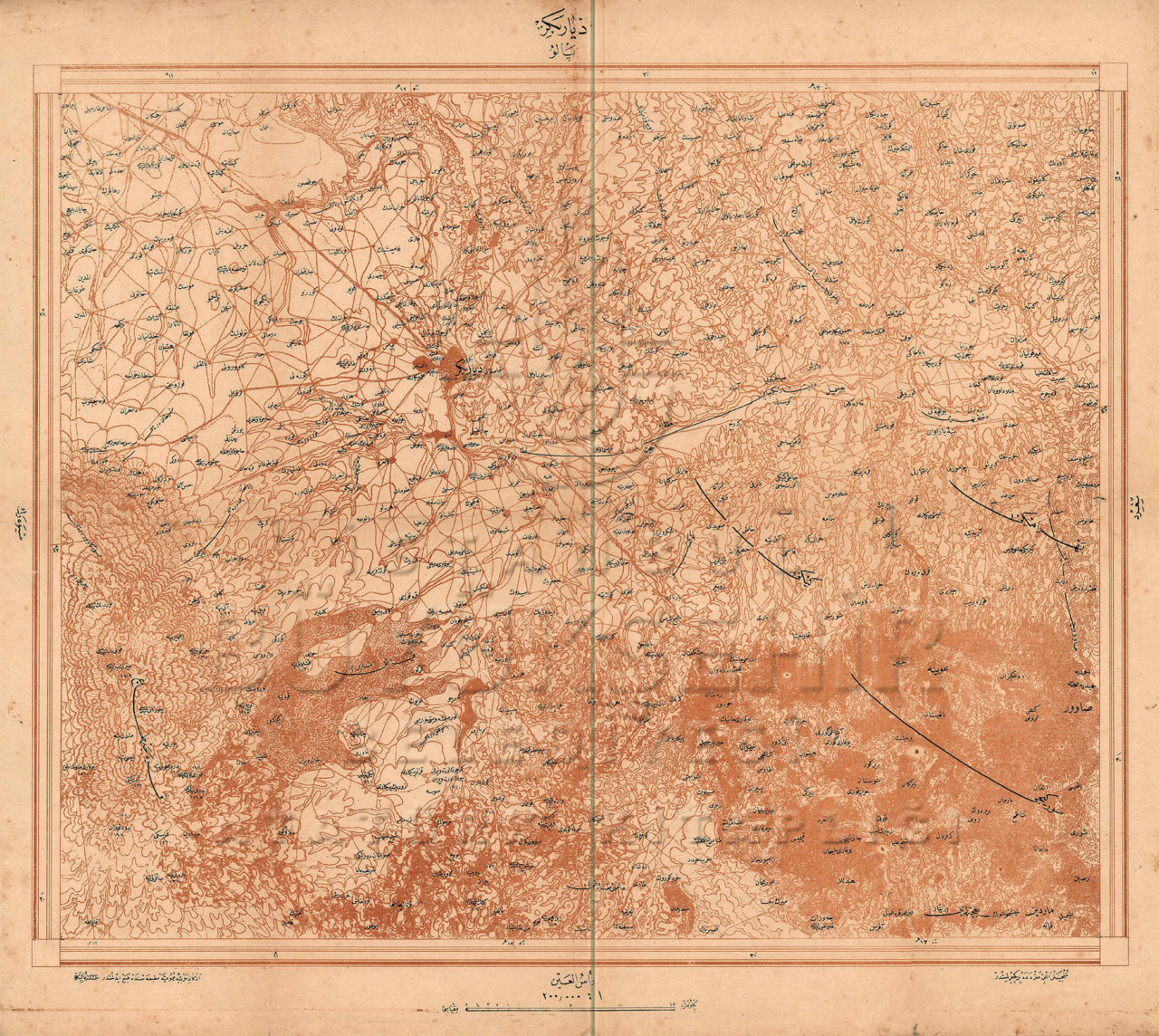

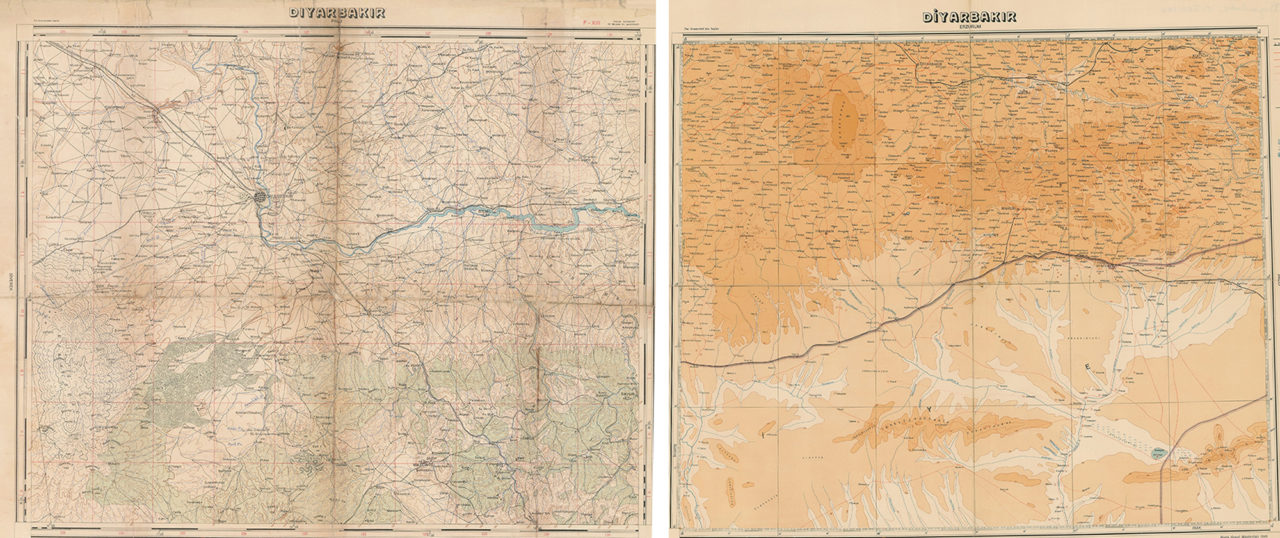

Again as World War 1 was ongoing, the Ottoman Empire too had had detailed maps of the Vilayets (Provinces) on the frontlines prepared under its Erkân-ı Harbiye-i Umumiye (Ottoman War Ministry), and these were printed in 1917. In the one of Diyarbekir, we see that not only the area’s topography but also various other details including even village roads have been provided.

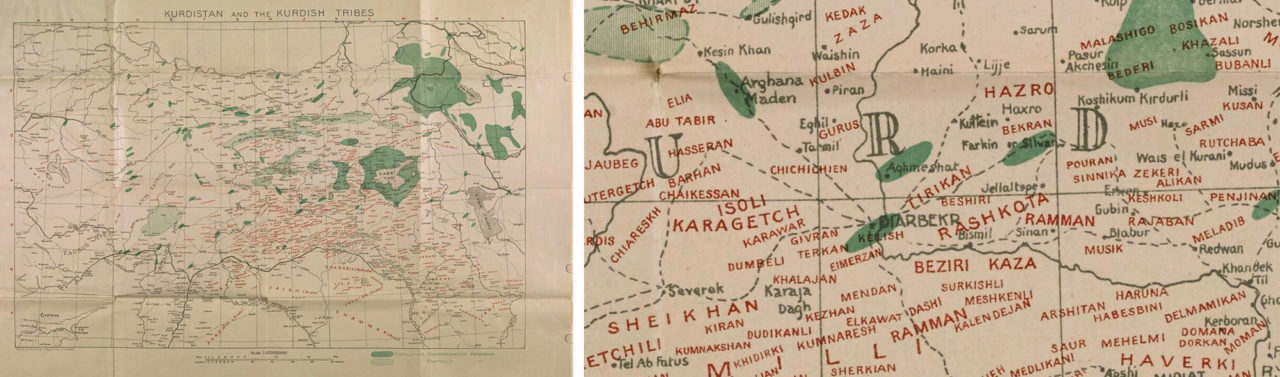

In 1908, Mark Sykes had conducted a survey of Kurdish tribes that lived under the Ottoman Empire. Data acquired as such led to the production of a map in 1919, which provided a detailed display of the geographic distribution of Kurdish tribes in the Diyarbekir region.

As the frontiers of the Ottoman Empire were being redrawn in the wake of World War 1, the commission in charge issued the maps of the latest state of affairs in 1920. With one of these, Turkey’s south-eastern border was effectively chalked out.

On the right: Map prepared by the General Directorate of Mapping (Harita Genel Müdürlüğü) in 1946.

The city’s name change following the founding of the Republic was reflected in new maps prepared. Two separate maps of Diyarbakır were produced by the Ankara-based Mapping Department in 1940 and then the General Directorate of Mapping in 1946.

Text: Dr. Yusuf Baluken

Translation: Feride Eralp