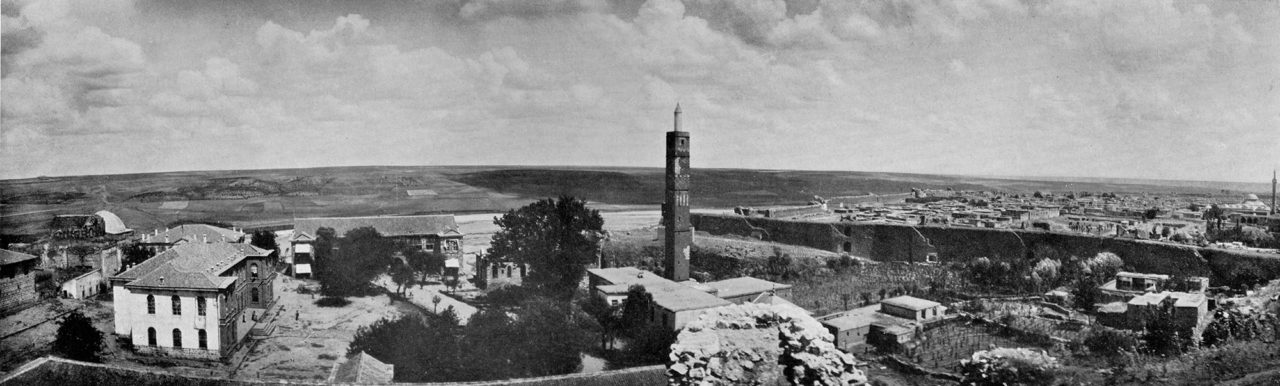

(Photograph: Josef Strzygowski, 1910)

Life has continued in cities since the early stages of human history, and the architectural identity of cities emerges as segments of civilisation are stacked one above the other, develop side by side, or intersect. Not only is Diyarbakır such a city, but it also developed an enriching relationship with every civilisation it has been part of throughout history: Assuming the colours of different civilisations, passing on traditions extending through millennia and expecting harmony from the new. This is an adventure that we are able to trace back in time: With this exhibition, it was our desire to take a tour of Diyarbakır, guided by architectural history, wandering from spaces of faith to public spaces and to residential structures.

Diyarbakır is located in the upper-middle section of the “Fertile Crescent”, where the Tigris River gives life to Northern Mesopotamia. Life in the city has continued uninterrupted from the Palaeolithic period to the present day. This continuity means that a cultural heritage of millennia is transmitted from one generation to the next, inscribed on its city walls, displayed in its streets or told through its oral literature. Diyarbakır has been the capital of many civilisations throughout history, and has hosted all the sedentary peoples of Mesopotamia, and also invading forces that conquered the city at war. As its multilingual, multi-religious, multi-national and multi-cultured history is also reflected in its architecture, the city occupies an important place in world architectural history.

Diyarbakır’s cultural layers can be either piled on top of each other, or placed side by side. Founded on the Karacadağ basalt plateau which is shaped like a turbot fish, in the middle of rich valleys nurtured by the Tigris River, Diyarbakır’s location on an important trade route connecting Asia to Anatolia via Mesopotamia, and its many water reserves further increase its importance: A self-sufficient city capable of producing surplus value. Its strategic geographical location, rich resources, abundance of basalt reserves and multicultural structure all played a role in shaping the city. In terms of architecture, it is possible to trace back all civilisations and cultures that have lived in the city both through inscriptions on the city walls and architectural works displaying period features. The oldest settlement of the city surrounded by walls is Amida Höyük, at Fiskaya. Archaeological excavations and research carried out here have revealed that this area was a small settlement during the Chalcolithic, Bronze and Iron ages.

Written historical sources indicate that the city constantly changed hands, from 331 BC on, between the administrations of Alexander the Great and the Seleucid, Parthian, Armenian, Roman and Sasanian empires. A letter written in 705 BC by the Assyrian Governor of Amidi states that he ordered the construction of a fortress, and within the fortress, a palace. The famous text dated 359 AD of Ammianus Marcellinus, who served as an imperial guard in the Roman army, tells us that the city was surrounded by walls and bastions by Constantius Caesar. Therefore, it is possible to define the Roman period in Amid, which was already a fortress-city, as a golden age when significant development took place, the city walls were renovated and the city’s borders and main axes were more or less determined.

![Melik Ahmet Mosque, built in the 16th century, is among the most outstanding monuments of the city with its çini [tile] ornaments to architectural elegance displayed at its intersections with the street. (The archive of Metin Sözen)](https://diyarbakirhafizasi.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/4-3-1260x1280.jpg)

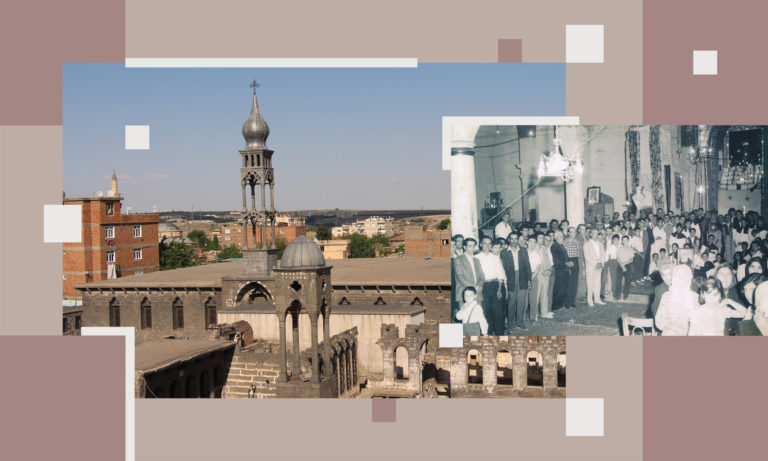

In the Islamic period that lasted over a millennium from the Roman-Byzantine and Sasanian periods to the Republican period, different ethnic powers, including Arabs, Kurds and Turks, ruled over the city. During the Umayyad, Abbasid, Hamdanid, Şeyhoğulları, Buyid, Marwanid, Seljuk, Inalid, Nisanid, Artuqid, Ayyubid, Aq Qoyunlu and Ottoman periods, the city underwent significant architectural change, as each of these dynasties ordered the construction of many religious, commercial and social buildings, symbolizing their rule. In the city Arab (Muslim), Armenian (Orthodox, Catholic, Protestant), Kurdish (Muslim, Christian, Ezidi [Yazidi]), Greek (Orthodox), Assyrian (Orthodox, Catholic, Nestorian, Protestant), Şemsi, Turk (Muslim) and Jewish communities lived together in the same neighbourhoods. This pluralist life style also had a clear impact on the city’s silhouette. But more importantly, it helped create, despite ethnic and religious differences, a common architectural style and aesthetic taste in the city.

![It is possible to fit, in the frame of a single photograph taken at Sur, the “Four-legged Minaret” of the Sheikh Mutahhar Mosque, the Mar Petyum Church, Ulu Cami [the Grand Mosque] and the Surp Giragos Armenian Church. (Photograph: Tamer Pınar, 2015)](https://diyarbakirhafizasi.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/sur_çanlar_minareler_tamer_pınar_08.07.2015-1280x840.jpg)

Although Diyarbakır frequently changed hands, it underwent repairs after every occupation, and new buildings were added in accordance with the requirements of the period. Even conquerors from the outside, in declaring their zone of dominance, chose to act in harmony with the city’s traditional architectural elements. Even if the rulers changed, those in charge of development often remained residents of the city, or architects and master builders from nearby provinces such as Urfa or Gorgan, which meant that the millennia-old traditional architecture continued with small innovations. The earliest records of names of architects in the Islamic world have been discovered in Diyarbakır. Many structures we know of from historical sources have been either damaged or completely destroyed, because the peoples who built them no longer live in the city, or because of wars, development policies of different periods and the shift of the city centre towards new and modern settlement areas. However, there are mosques, churches, remains of synagogues, türbes [tombs], madrasas, hans [commercial buildings] and hammams [baths], public buildings, military barracks, hospitals and schools that continue to stand side by side despite everything, with some still functional.

In all the periods of the city, a construction tradition based on the use of basalt, formed from the lava of the Karacadağ volcano and quarried from the rich stone pits nearby and lime mortar. Brick and wood stand out as materials used in the architectural cover, while yellow limestone, quarried in Ergani and its environs, is used frequently in ornamentation. The alternating technique of black-and-yellow stone, developed in order to contrast the dark and strong expression of basalt, is used especially on façades. The courtyard is one of the fundamental elements in the creation of any architectural plan in the city, where summers are very hot. Without exception, residential, religious, commercial or social architecture all feature and are shaped around an inner courtyard. The same can be observed in Christian architecture, represented by a great number of buildings in the city. Churches and monasteries of different denominations, constructed during different periods all uphold this tradition.

![An unadorned, plain style is often preferred on the façades of buildings that face the city’s narrow streets. However, façades that face the courtyard are the exact opposite. In the photograph, we see the mabeyn [the ‘in-between’ room] of the Cahit Sıtkı Tarancı House opening onto the courtyard with an embellished door.](https://diyarbakirhafizasi.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/7-3-868x1280.jpg)

Façades facing the courtyard are designed in a highly dynamic and ornamental manner, while street façades have often been imagined as blind and massive structures. Ornamentations on the courtyard façades focus around symmetrically aligned doors, windows and niches. Geometric and stylized botanical patterns and figurative reliefs are frequently seen in façade ornamentation. Although ornamentation in Islamic architecture is often restricted to geometric and botanical patterns because of the prohibition on figure drawing, figures are frequently used especially in Artuqid and Ayyubid period buildings in Diyarbakır. Animal- or fantastic-figures such as the lion, bull, horse, rabbit, deer, ram, sheep, peacock, eagle, rhinoceros, griffin, sphinx or dragon not only symbolizes power, but are also thought to have been charms to protect the buildings. Although limited in number, there are also façades featuring human figures.

A plain style is generally preferred in Diyarbakır buildings, however, in interiors and especially in buildings from the Aq Qoyunlu and Ottoman periods, tile and wood ornamentations are featured profusely. In churches, which stand out with their plain façade design, the alternating use of two different colours of stone, multi-cusped arched windows and muqarnas vaulting add dynamism to façades, while we come across figurative ornamentation and religious symbols of Christianity in interiors.

Text: Associate Professor Birgül Açıkyıldız, Art historian

Translation: Nazım Dikbaş

BIBLIOGRAPHY

• Assénat, M. (2015) “Amida Surları: Birkaç Tarihi ve Kronolojik Unsur”, Diyarbakır Kalesi ve Hevsel Bahçeleri Kültürel Peyzajı, (ed.) Nevin Soyukaya, Diyarbakır Büyükşehir Belediyesi Diyarbakır Kalesi ve Hevsel Bahçeleri Kültürel Peyzajı Alan Yönetimi Başkanlığı Yayınları, Istanbul: 29-48.

• Baş, G. (2013) Diyarbakır’daki İslâm Dönemi Mimari Yapılarında Süsleme, Türk Tarih Kurumu, Ankara.

• Beysanoğlu, Ş. (2019) Anıtları ve Kitabeleri ile Diyarbakır Tarihi, Volumes 1-2-3, Diyarbakır.

• Gabriel, A. (1940) Voyages Archéologiques dans la Turquie Orientale, Paris: 197-199.

• Hillez Halifeoğlu, S. (2016) Güneydoğu Anadolu Bölgesinde Bulunan Ermeni Kiliseleri Koruma ve Kullanım Durumları, Master’s Thesis, Dicle University, Diyarbakır.

• Karadoğan, S. (2015) “Yerleşmeye Etkileri Açısından Diyarbakır Kenti ve Yakın Çevresinin Doğal Peyzaj Unsurları”, Diyarbakır Kalesi ve Hevsel Bahçeleri Kültürel Peyzajı, (ed.) Nevin Soyukaya, Diyarbakır Büyükşehir Belediyesi Diyarbakır Kalesi ve Hevsel Bahçeleri Kültürel Peyzajı Alan Yönetimi Başkanlığı Yayınları, Istanbul: 1-16.

• Ökse, T. (2015) “Amida Höyük Bulguları ve Tarihi Belgeler Işığında Eski Çağda Diyarbakır”, Diyarbakır Kalesi ve Hevsel Bahçeleri Kültürel Peyzajı, (ed.) Nevin Soyukaya, Diyarbakır Büyükşehir Belediyesi Diyarbakır Kalesi ve Hevsel Bahçeleri Kültürel Peyzajı Alan Yönetimi Başkanlığı Yayınları, Istanbul: 17-28.

• Sönmez, Z. (1989) Başlangıcından 16. Yüzyıla Kadar Anadolu Türk-İslam Mimarisinde Sanatçılar, Türk Tarih Kurumu, Ankara.

• Sözen, M. (1971) Diyarbakır’da Türk Mimarisi, Istanbul.

• Tuncer, O. C. (2015) Diyarbakır Camileri, Diyarbakır.

EXHIBITION CREDITS

Contributing authors

Assoc. Prof. Birgül Açıkyıldız, Dr. Mehmet Atlı, Jaklin Çelik, Assoc. Prof. Meral Halifeoğlu, Truman Şakarer, Seîd Veroj

Exhibition editor

Pınar Öğünç

Translation

Murat Bayram, İnan Eroğlu (Kurdish)

Nazım Dikbaş (English)

Design

Fika

Publication date

March 2020