It is no wonder that so many Diyarbakır folk songs mention silk. In both the economic and the social sense, of all types of textiles production have deep roots in Diyarbakır and its environs, both silk production and weaving have always been important. In the Ottoman Empire, after Bursa, Diyarbakır was among the first cities that came to mind regarding silk production.

There are both global and local reasons for the Ottoman Empire losing its place in the world market and for silk production and textiles no longer being the main economic activity in the region. And those mulberry trees are long gone…

Nevertheless, silk is a product that still retains its cultural meaning and is an important indicator as we consider the city’s history of production.

Our oldest knowledge on silk was recorded by the Chinese; and silk then spread from Central Asia to the rest of the world. It is believed that silk arrived in Anatolia in the 6th century. From the late 14th century on, the period when the Ottoman Empire begins to lead the global market in silk production. With Bursa the centre, cities like Diyarbakır, Istanbul, Edirne, Amasya, Denizli, İzmir and Konya led in the production of silk. In the mid-19th century, there were fourteen silk factories that worked by water or steam power and around thousand silk looms with an annual capacity able to produce over 31 tonnes of silk. One third of the raw production across the empire was sent to Diyarbakır, Aleppo and Damascus to be used in weaving.

The subjection of the domestic silk industry to excessive taxes, the mechanization of weaving in Europe, and the resulting decrease in labour costs meant that the domestic producer could not compete, and in time, roles began to change in this market.

Source: Zahide İmer, “Diyarbakır’da ipekçilik ve dokumacılık [Sericulture and weaving in Diyarbakır]”.

![This document, signed by Voivode of Diyarbekir Halil, was written to Selim III, asking for approval for the opening of mengenehane [weaving houses] where textiles such as alaca, kutni and others were to be produced in Diyarbakır, as in cities such as Istanbul, İzmir, Bursa, Aleppo and Thessaloniki. The Sultan then approves the opening of mengenehane and the taxing of their products on 10 May 1797 (13 Zilkade 1211, Hijri). (Directorate of State Archives, Ottoman Archives)](https://diyarbakirhafizasi.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/1_ipek-3-801x1280.jpg)

Silk is a more recent product in human history, however, the history of weaving dates back to much older times in the Diyarbakır area.

Excavation data from Çayönü reveals that the Neolithic settlement was founded to the south of a stream with a wide riverbed flowing through the plain and surrounded by reed beds and probably marshland, and that the riverbed of present day Boğazçay was formed around 3,000 BC. The flax plant, which loves water, is a natural part of this environment. Structures in Çayönü are mostly stone, or a mixture of stone and adobe, however, the shelters of the Pothole Shelters Phase were weaved from reed, straw and thin branches. In consideration of the fact that the cover coat of Grid Plan Structures displays similar features, and the existence of basket and matting weaving, it is possible to speak of a close relationship between the people of Çayönü and reed fields. This should also be the time when the flax plant attracted their attention. At the phase of Late Cell-Plan Buildings, dated to around 9323-9450 BC, calcified remains on the handle of a seared horn sickle found in a burned-down building belong to a piece of cultivated linen cloth. Specialists’ views prove that this piece of cloth was weaved from flax fibre spun with an advanced spinning technique.

Prof. Dr. Aslı Özdoğan

With a millennia-long-history that begins in China and extends to India, Byzantine lands and Europe, silk was always part of global and regional networks in Diyarbakır. The manifestation in places like Bursa and Diyarbakır of the Industrial Revolution in Europe, which had a universal impact, was the blow it struck to economies defined with traditional techniques, such as sericulture, weaving, the leather trade and other hand crafts. Yet, according to economic historians, Diyarbakır was an important centre for textiles, and especially silk manufacturing and trade. One of the first modern craft schools in the city was part of Sümerbank, a leading investment project of the Republic, which has today been transformed into Sümerpark.

Dr. Mehmet Atlı, Researcher, Writer

As it stood at an important intersection on the Silk Road for centuries, Diyarbekir acquired significance in silk production. It could be said that, in the early modern period, it remained slightly in the shadow of other cities where silk was produced, such as Mardin, Maraş and Aleppo; however, in terms of local consumption, especially for wealthy families, silk was highly sought after.

According to British consular reports, in Diyarbekir, where silk worth 10,338 pounds that had come from Amasya and Bursa had been weaved in 1863, local production continued, and despite falling labour wages, the city managed to remain standing in competition with western products. Despite all the [negative] circumstances, silk was one of the significant export items of the Ottoman Empire.

Dr. Uğur Bayraktar, Historian

Traveller James Silk Buckingham, who visited Diyarbakır in 1827, wrote the following in his travelbook:

“The manufactures of the town are chiefly silk and cotton stuffs, similar to those made at Damascus; printed muslin shawls and handkerchiefs, morocco leather in skins of all colours (…) There are thought to be no less than fifteen hundred looms employed in weaving of stuffs; about five hundred printers of cotton, who perform their labours in the Khan Hassan Pasha (…) three hundred manufacturers of leather in the skin, besides those who work it into shoes, saddlery, and other branches of its consumption…”

Source: M. Şefik Korkusuz, Seyahatnamelerde Diyarbekir [Diyarbekir in Travelbooks], Kent Yayınları, 2003.

The great majority of those involved in silk weaving were Armenian, and silk fabric production suffered a great blow after the genocide. Grigor Torgomian wrote a book on sericulture in Ottoman in 1922, however, by this point, Armenians no longer controlled this industry. The silk factory of the Tırpancıyan family had been seized by two notable families of Diyarbekir in 1915. They modernized the silk looms, continued production and also received practical and financial support from the vocational school founded by the new Republic in 1930. At the İzmir Fair, Diyarbekir’s contribution to “national economy” was tested via its silk production. Despite the founding of other factories, the collapse of the silk industry could not be prevented. While 324 villages produced silk in 1933, this figure had dropped to 79 by 1937.

Some Armenians among those forcibly deported to Deir-ez Zor and Aleppo continued this traditional craft where they ended up. In fact, they provided their old neighbours, now on the other side of the border, with the high-quality silk products they manufactured. Following a visit to the area, Şükrü Kaya, the Interior Minister of the period, proposed the interruption of this flow to the region. However, this could not prevent the collapse of the silk textile industry in the city either.

Uğur Bayraktar

Other than silk, Diyarbakır was an important city for cotton weaving, and wool carpet and rug manufacturing. Gürün shawls, kutnu, alaca and dalsar fabrics, Ankara mohair and linen cloth were all products specifically sought out in Europe until the 20th century. This richness, in a region that already displayed diversity in terms of faith, culture and ethnicity, was reflected in the attire of the people.

The album of photography titled “Elbise-i Osmaniye” is a realistic and powerful source that shows this. The Ottoman State had prepared for its participation at the 1873 Vienna World’s Fair with a team led by Osman Hamdi Bey. The texts and design of this album belong to Osman Hamdi Bey and Marie de Launay, while the photographs were taken by Pascal Sébah. “Elbise-i Osmaniye” is a highly important document in that it meticulously records what the peoples that formed the Ottoman State in the second half of the 19th century wore. Its contemporary worth is also increased by the refusal of Osman Hamdi Bey and Marie de Launay to lean towards the orientalist gaze the target audience of the album, i.e. European readers, were accustomed to. For instance, all the compositions were shot in front of an empty background and every text features meticulous detail.

The three women and three men in the two photographs in this album shed light on the various types of attire worn in Diyarbakır and its environs. In separate shots for women and men, the dress of a Muslim from Diyarbakır, a Christian from Diyarbakır and a Kurd from Palu, reveal differences not only among themselves but with other parts of the empire as well.

Source: Mehmet Emin Kahraman and İsmail Erim Gülaçtı, “Elbise-i Osmaniye: 1873 Viyana Uluslararası Sergisi’nde bir yaratıcı endüstri örneği [Elbise-i Osmaniye: An example of creative industry from the 1873 Vienna World Fair]”, Beykoz Akademi Dergisi, 4(2): 20-42, 2016.

![The Ottoman State prepared for its participation at the 1873 Vienna World’s Fair with a team led by Osman Hamdi Bey. “Elbise-i Osmaniye” [“Popular Costumes in Turkey in 1873”] is a precious album of photography on the occasion of the fair. (Library of Congress)](https://diyarbakirhafizasi.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/7_ipek-931x1280.jpg)

![Photographs for the album titled “Elbise-i Osmaniye” [“Popular Costumes in Turkey in 1873”] prepared for the 1873 Vienna World’s Fair were taken by Pascal Sébah. In one shot, a Kurd from Palu, a Muslim from Diyarbakır and a Christian from Diyarbakır, all married women, are shown in their traditional attire. In the other shot, the men are a Christian from Diyarbakır, a Muslim from Diyarbakır, and a Kurd from Palu. (Library of Congress)](https://diyarbakirhafizasi.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/88-1280x936.jpg)

Puşi is a type of headscarf and an important part of the traditional attire of both women and men. Made from patterned or plain silk fabric, puşi has been used by Kurds, Yörüks, Turkomans, Armenians and Assyrians. The word for it in Ankara is “poşuğ”, in Bitlis “poşi”, and in the Black Sea region, the word “şar” is also used beside puşi.

Although difficult to separate from weaving, puşi making is a craft performed mostly by Assyrians and to some extent, Armenians, in Diyarbakır and its environs. Puşi is mentioned in many regional folk songs as well. Today, however, both the manufacturing type, fields of use and meanings ascribed to the puşi have changed.

Source: Zahide İmer, “Diyarbakır’da ipekçilik ve dokumacılık [Sericulture and weaving in Diyarbakır]”.

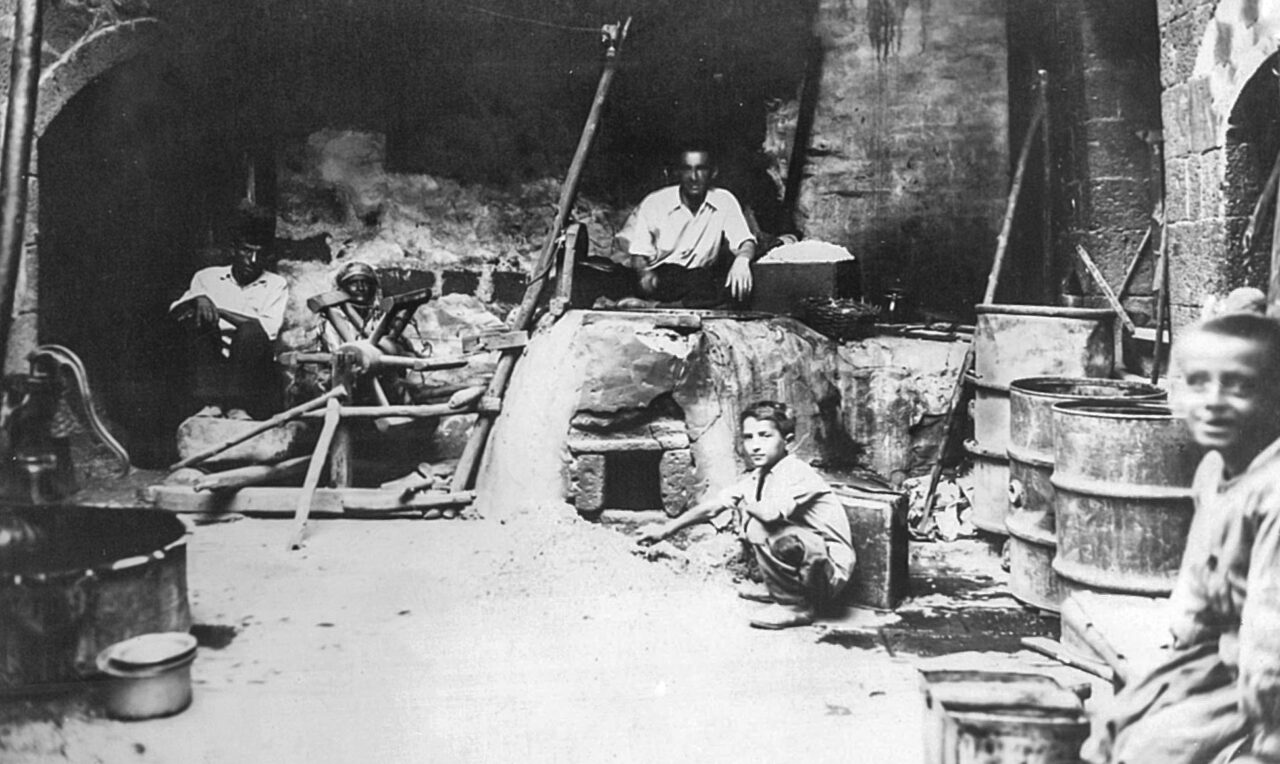

“Sericulture and silk weaving was widespread in Diyarbakır. There was a neighbourhood known as Sinek Pazarı, to the west of Cemil Paşa Konağı, the Cemil Pasha Mansion, it’s the street where the Saint Mary Church is, that’s where the silk weaving workshops mostly were. There were five or six large workshops. Besides, for instance, when the Cemil Pasha family was in exile, there was a silk weaving and puşi manufacturing workshop in a section of the Cemil Pasha Mansion. In fact, oud player Yervant Bostancı’s father, Yakup (Hagop), known as Keke Yako, was a master craftsman there.

The last time we toured Diyarbakır together, he (Yervant Bostancı) told us this, he is, too, after all, a kid of the Hançepek neighbourhood, just like Mıgırdiç (Margosyan). The sound of looms could be heard from the workshops in Sinek Pazarı, like a sweet melody, the craftspeople would work in such harmony. And they, too, would enjoy their work, they would sing songs and folk songs as they weaved puşi.

Silk cocoons were produced at some houses, mostly in the Ali Paşa and Behram Paşa neighbourhoods, and this brought an income, of course. Leaves of the mulberry tree would be brought in. At the Gazi Kiosk, from Mardinkapı right to Ongözlü Köprü (‘Ten Arches Bridge’) there were two lines of mulberry trees. There were mulberry trees in all the gardens as well. Leaves from these trees would be brought to cocoon producers in the city and sold here.”

From an oral history study carried out with journalist and researcher Mehmet Mercan, who was born in 1935 in the Alipaşa neighbourhood of Diyarbakır

“Until the mid-1970s, the silk puşi shops were at Mardinkapı, between Balıkçılarbaşı and Mardinkapı, but then they disappeared, too. Why did they disappear? The Assyrian master craftspeople there, shop owners, some of them passed away, and some of them, you know, left Diyarbakır. When the mulberry trees went, cocoon production ended, and the craft of puşi making ended, too. For instance, there was Koza (literally, cocoon) Hanı in Diyarbakır. The Balıkçılarbaşı Post Office was used as a silk cocoon exchange. There was a silk han at Urfakapı. When silk traders came to trade, they would stay at that han. It’s no longer there. The silk industry has almost died away. Now I hear that, a few years ago, at some districts, Kulp especially, they are trying to revive the silk industry, with initiatives led by district governors. It would be great if they succeed, of course.”

From an oral history study carried out with journalist and researcher Mehmet Mercan, who was born in 1935 in the Alipaşa neighbourhood of Diyarbakır

Silk production is tied to the silkworm, and the silkworm needs mulberry leaves, this, and the current problems of production in some districts, especially Kulp, have become the subject of academic theses and reinvigoration projects. The city is first in Turkey in terms of cocoon production, however, despite this statistical data, the city centre appears to have long severed its tie with silk. Any connection with the consumption of silk takes place, as it does everywhere else, through global brands sold at shopping malls.

Mehmet Atlı

In 1930, the Ministry of Agriculture opened the Regional Silkworm Breeding Station in Diyarbakır. Significant silkworm farming was carried out in the 1970s in, first and foremost, Diyarbakır city centre, and also in the districts of Silvan, Lice, Kulp and Hazro. However, economic and political developments and related migration meant that production almost stopped.

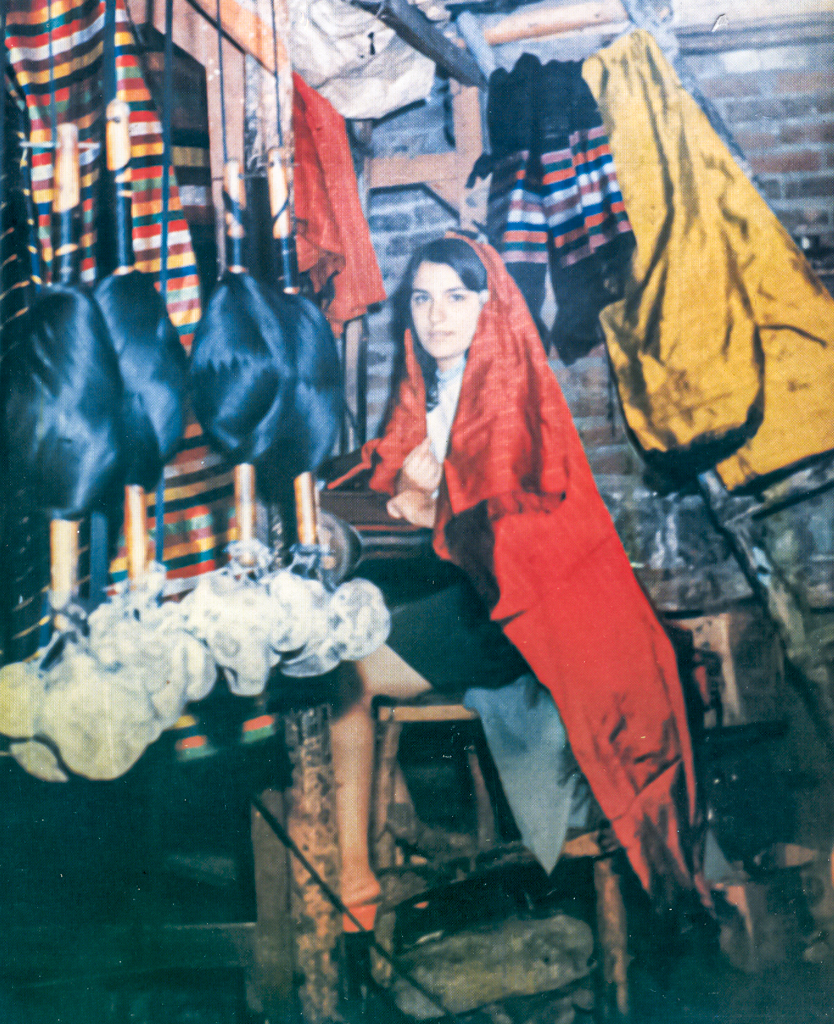

Then, from the 2000s on, Diyarbakır silkworm farming and silk textiles once again came into prominence. In a number of newly developed projects, workshops where especially women were employed for hand-woven puşi manufacturing in the Kulp district and its villages.

Source: İlkay Barıtcı, Cemal Adıgüzel and Murat Kanat, “Diyarbakır ilinde ipekböceği yetiştiriciliğinin genel durumu [An overview of silkworm farming in Diyarbakır province]”, Dicle Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü Dergisi, 6(2): 77-82, 2017.

Translation: Nazım Dikbaş

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aslı Özdoğan

• Alfaro Giner, C. (2012) “Textile from the Pre-Pottery Neolithic Site of Tell Halula (Euphrates Valley, Syria)”, Paléorient, 38(1-2): 41-54.

• Caneva, I., Davis, M., Marcollongo, B., Özdoğan, M. and Palmieri, A. M. (1993) “Geo-archaeology in the Northern Diyarbakır Region”, Essays on Anatolian Archaeology, Bull. of the Middle Eastern Culture Center in Japan, VII, (ed.) T. Mikasa, Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden: 161-168.

• Erim-Özdoğan, A. (2011) “Çayönü”, The Neolithic in Turkey: New Excavations & New Research, The Tigris Basin, (ed.) M. Özdoğan, N. Başgelen, P. Kuniholm, Archaeology & Art Publications, Istanbul: 185-269.

• Van Zeist, W. ve de Roller G. J. (1994) “Plant Remains from Aceramic Çayönü, SE Turkey”, Palaeohistoria, 33/34 (1991/1992): 65-96.

• Vogelsang-Eastwood, G. (1993) The Çayönü Textile (unpublished report).

Uğur Bayraktar

• Buckingham, J. S. (1827) Travels in Mesopotamia Including a Journey from Aleppo to Bagdad by the Route of Beer, Orfah, Diarbekr, Mardin, & Mousul, Vol. 1, London.

• Pamuk, Ş. (2018) Uneven Centuries: Economic Development of Turkey since 1820, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

• Quataert, D. (1993) Ottoman Manufacturing in the Age of the Industrial Revolution, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

• Sami, Ş. (1891) “Diyarbekir”, Kamusu’l-A’lâm [Encyclopaedia of General Science], Mihran Matbaası, Istanbul.

• Üngör, U. Ü. and Polatel, M. (2011) Confiscation and Destruction: The Young Turk Seizure of Armenian Property, Continuum, London.

• Yadırgı, V. (2017) The Political Economy of the Kurds of Turkey: From the Ottoman Empire to the Turkish Republic, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.