Diyarbakır is founded at an intersection of the Upper Tigris Basin, Mesopotamia, Syria, Iran, the Mediterranean and Anatolia, and was an important trade centre throughout its history. The dynamism and requirements brought on by this role also shaped its architecture. Hans, commercial buildings where caravans stopped over and merchants carried out their activities, are among the main components that define the city’s character. Hasan Paşa Hanı is one of the largest extant Ottoman hans. Following restoration work initiated in 2006 by the Diyarbakır Foundations Directorate, the han today is a centre of social life with its breakfast-cafés and souvenir shops, and one of the most popular stops on tourist trails. Despite certain interventions that have harmed the unique structure of the building and debates over its role as a tourist attraction, Hasan Paşa Hanı remains one of the most important meeting points of the city.

Architect and writer Mehmet Atlı has interpreted photographs from three different periods of Hasan Paşa Hanı for this exhibition.

Diyarbakır stands out with its strategic location, and this also meant that it has been a city of trade throughout its history, and a constant stop-over for caravans from Iran, Iraq and Azerbaijan.

The presence of hans and caravanserais is a further reflection of trade activity in the city. Although the word han is often used interchangeably with caravanserai, the two structures are quite different both in terms of architecture and function. Caravanserais are founded on less-frequented intercity roads, and prioritize safety of life and property, and therefore tend to be structures that resemble fortresses. Caravanserais are often the only structure along a “menzil” or distance of eight to ten hours by foot, and therefore include hamam [bath], çarşı [market] and stable sections. Yet once in the city, such functions are not equally essential. Hans, therefore, are often founded on main intercity roads and sometimes in the commercial section of a city, and serve the functions of trade and accommodation: They are part and parcel of city life.

Kepo Han, at the Kepo (Başdeğirmen) village of Diyarbakır’s Silvan (Farqîn) province and near the Malabadi Bridge, is considered the earliest han, or commercial building, in Anatolia. Built in the 1000s, during the Marwanid period, the structure is now in a derelict state.

• Aydemir, H. (1969) Silvan ile Tatvan Arasındaki Hanlar, undergraduate thesis, Istanbul University Faculty of Literature Department of Art History, Istanbul.

• Baran, M. (2008) “Osmanlı Dönemi Diyarbakır Hanları’nda Yöresel ve Mimari Üslup”, Osmanlı’dan Cumhuriyet’e Diyarbakır 2, (ed.) Bahaeddin Yediyıldız and Kerstin Tomenendal, Diyarbakır Valiliği Yayınları, Ankara: 557-565.

In provinces and villages, there are many han buildings along roads that connect Diyarbakır to old trade routes. On the other hand, only four of the many Ottoman-period hans in Sur, the city centre, have survived. Deliller Hanı (also known as Hüsrev Paşa Hanı), built upon the orders of Hüsrev Paşa in 1527, is on the immediate right of the Mardinkapı entrance of the city. The word “delil” in the han’s name, means guide, denoting the fact that guides accompanying prospective hadjis stayed here at this han. The wide space opposite the han has been named Hacılar Harabesi [Hadji Ruins]. Typically Ottoman in terms of its architecture, this han has been a five-star hotel since 1984.

The other, Çifte Han, to the east of Gazi Street, is believed to have been constructed in the 16th century. Unique in terms of its two-part structure, one part was, unfortunately, demolished during roadwork. Used as an exchange building until its partial demolition, the building is in a derelict state today and is used only as a warehouse.

The third, Sülüklü Han, is one of Diyarbakır’s most popular meeting points today. Built in the year 1680 upon the orders of Hanilioğlu Mahmut Çelebi and his sister Atike Hatun, the han takes its name from the sülük, or leeches, that used to be kept in the fountain in its courtyard and were used for healing purposes. An important tourist attraction, a café operates in Sülüklü Han’s courtyard today.

The fourth and one of the largest extant hans is Hasan Paşa Hanı.

• Baran, M. (2008) “Osmanlı Dönemi Diyarbakır Hanları’nda Yöresel ve Mimari Üslup”, Osmanlı’dan Cumhuriyet’e Diyarbakır 2, (ed.) Bahaeddin Yediyıldız and Kerstin Tomenendal, Diyarbakır Valiliği Yayınları, Ankara: 557-565.

• Güneli, Z. and Kejanlı, T. (1999) “Diyarbakır Osmanlı Dönemi Mimari Yapılarından Günümüzde Ayakta Kalan Hanlar ve Özellikleri”, Diyarbakır: Müze Şehir, (ed.) Şevket Beysanoğlu, M. Sabri Koz and Emin Nedret Dişli, Yapı Kredi Yayınları, Istanbul: 252-257.

The construction of Hasan Paşa Hanı took place from 1572 to 1575 upon the orders of Vezirzâde Hasan Paşa, Governor of Diyarbakır and the son of Grand Vizier Sokollu Mehmed Paşa. It is located to the east of Ulu Cami, on Gazi Street. Hasan Paşa had previously ordered the construction of another han, for the jewellers of the city, but that building, known as Ketenciler, has not survived. Hasan Paşa Hanı is built around a two-floor cloistered courtyard, and has three inscriptions, at the southern, eastern and market entrances.

The lower floor was for the stables. As in all Ottoman han architecture, the first floor was reserved for the accommodation for guests, and completely separated from the ground floor.

• Baran, M. (2008) “Osmanlı Dönemi Diyarbakır Hanları’nda Yöresel ve Mimari Üslup”, Osmanlı’dan Cumhuriyet’e Diyarbakır 2, (ed.) Bahaeddin Yediyıldız and Kerstin Tomenendal, Diyarbakır Valiliği Yayınları, Ankara: 557-565.

• Beysanoğlu, Ş. (2003) Anıtları ve Kitabeleriyle Diyarbakır Tarihi, Volume 2, Diyarbakır Büyükşehir Belediyesi Yayınları, Ankara: 619-622.

• Güneli, Z. and Kejanlı, T. (1999) “Diyarbakır Osmanlı Dönemi Mimari Yapılarından Günümüzde Ayakta Kalan Hanlar ve Özellikleri”, Diyarbakır: Müze Şehir, (ed.) Şevket Beysanoğlu, M. Sabri Koz and Emin Nedret Dişli, Yapı Kredi Yayınları, Istanbul: 252-257.

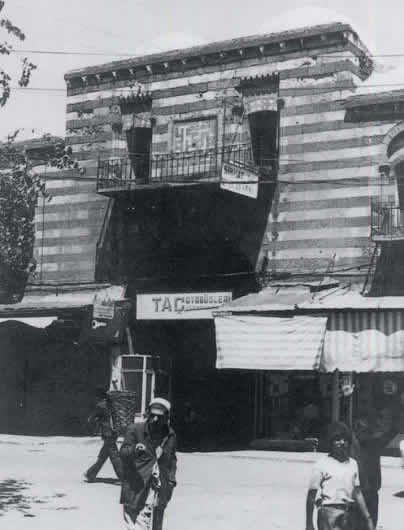

Balconies are later additions to the rooms on the western façade of Hasan Paşa Hanı. Shops in the western wing have been reserved for commercial activity through all historical periods. Today, on the ground floor, there are small souvenir shops, and on the upper floor, cafés serving breakfast.

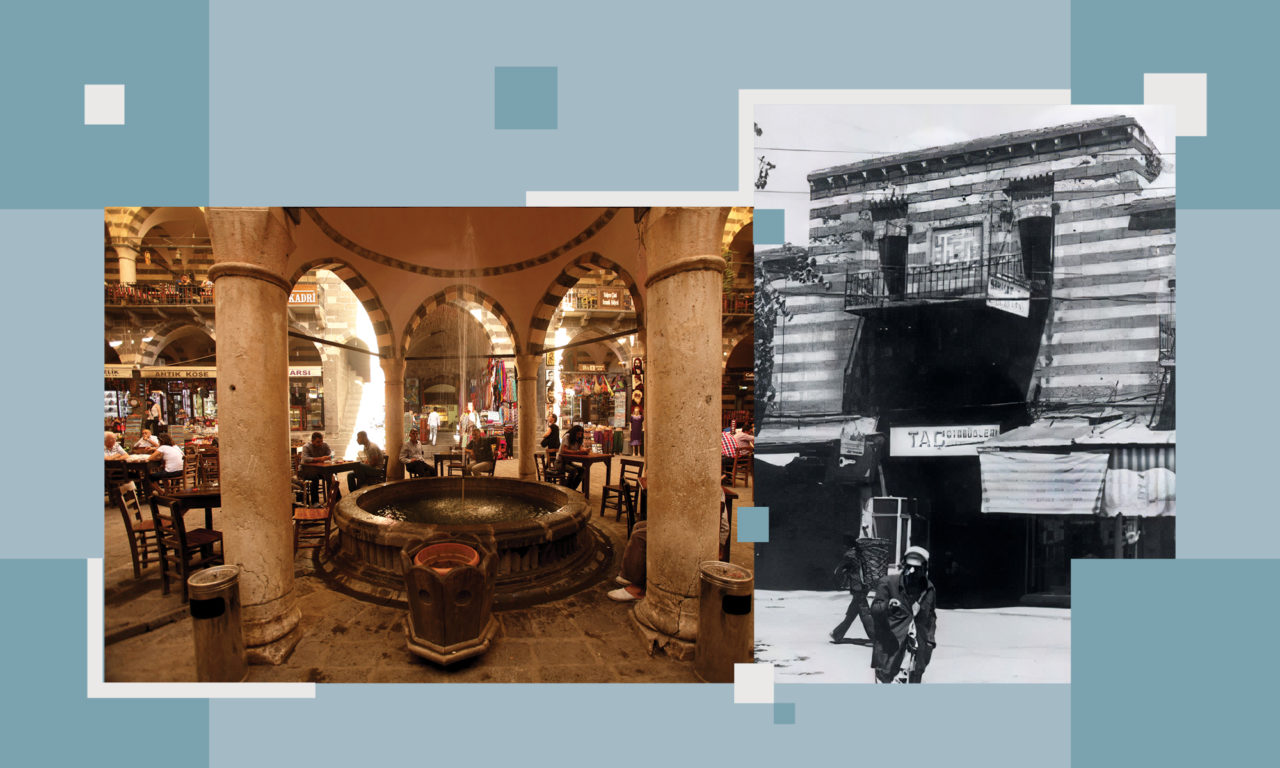

Basalt and limestone have been used alternately across the han, and especially the horizontal application of limestone brings an elongated appearance to the structure. There is a domed fountain structure supported by six columns in the courtyard.

• Baran, M. (2008) “Osmanlı Dönemi Diyarbakır Hanları’nda Yöresel ve Mimari Üslup”, Osmanlı’dan Cumhuriyet’e Diyarbakır 2, (ed.) Bahaeddin Yediyıldız and Kerstin Tomenendal, Diyarbakır Valiliği Yayınları, Ankara: 557-565.

• Güneli, Z. and Kejanlı, T. (1999) “Diyarbakır Osmanlı Dönemi Mimari Yapılarından Günümüzde Ayakta Kalan Hanlar ve Özellikleri”, Diyarbakır: Müze Şehir, (ed.) Şevket Beysanoğlu, M. Sabri Koz and Emin Nedret Dişli, Yapı Kredi Yayınları, Istanbul: 252-257.

Hasan Paşa Hanı is also mentioned in the works of travelogues visiting the city. Evliya Çelebi, in his seyahatname, or book of travel, praised the han’s size, solidity and facilities. Simeon of Poland, on the other hand, wrote the following for the han in the 17th century:

“…A magnificent stone masonry building, this han has two stables below ground that can hold up to 500 horses, a beautiful pool circled by colourful iron railing, and many stone masonry rooms across three floors.”

Andreasyan, H. D. (1964) Polonyalı Simeon’un Seyahatnamesi.

1.

The long lives of some buildings, transcending those of both individuals and generations, lends them a complex temporality; and links them to the diverse problems of architectural theory. It is possible to speak of a complexity regarding such buildings, reflected in their use and functions at different times. The rigid assumptions of modernism, and especially functionalism, aimed at assigning a certain function, above and beyond time and space, and inherent to structure and form, is rendered entirely contentious by such examples.

On the other hand, although photographs capture a single “moment”, their representation goes beyond that moment. There are few visual records of Hasan Paşa Hanı considering its age, and images from different periods provide clues regarding the progress of its life, and sheds light on the city and city life it is part of.

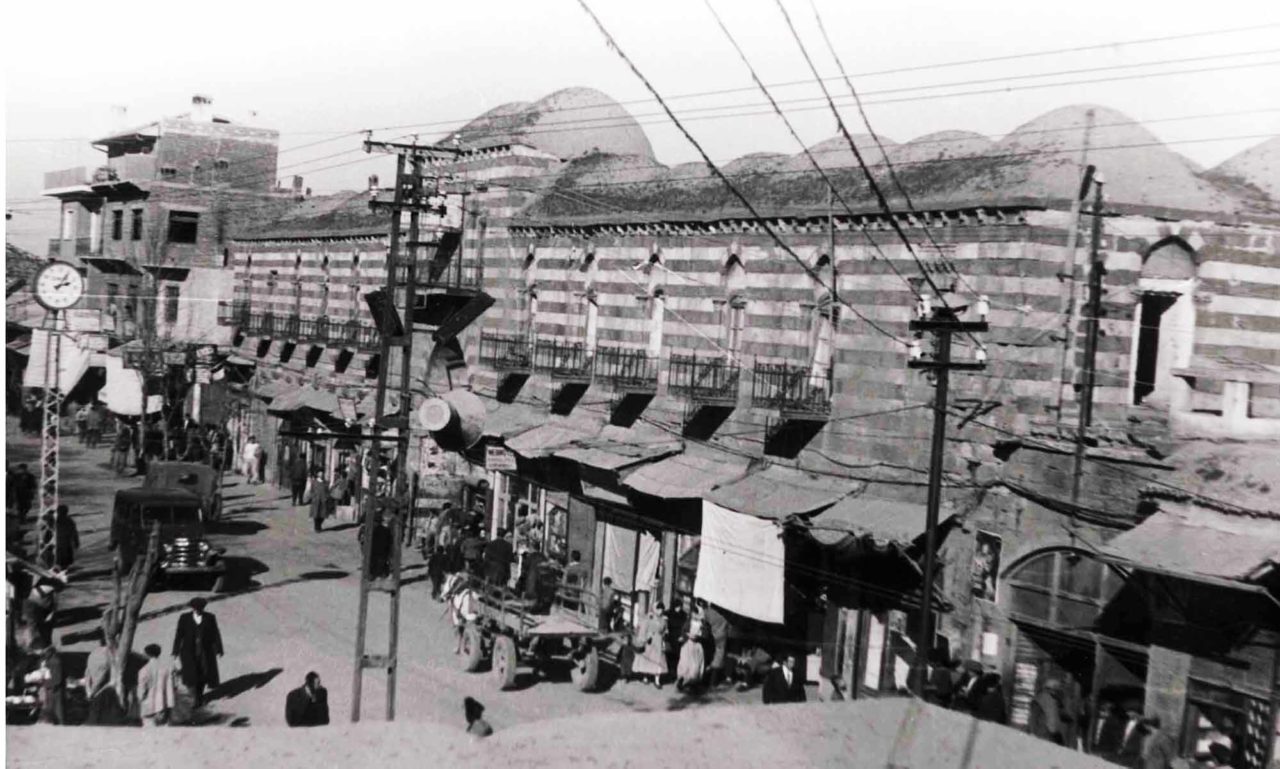

This photograph of the han, taken in the early 20th century, marks a country and city caught up in war. This military use of the building, despite its true function related to the commercial life of the city, also became the fate of churches, mosques and mesjids built for religious purposes, and of warehouses and city walls. The photograph documents a moment during the most tragic stage of war, destruction, massacre and alienation in a city which was already not experiencing the brightest period of its commercial life. Thus we meet a social and historical section on the scale of the city and a single building of a war on a universal scale, from a time when everything strayed from its purpose and context.

Mehmet Atlı, Architect, Writer

2.

Although this photograph of Hasan Paşa Hanı reflects a relatively calm time of the city in terms of the Republican period, it is nevertheless also a document where the “provincialization” and isolation policies implemented along with the establishment of the Republic can be discerned. It displays the fact that in Diyarbakır, where historical buildings have been abandoned to their fate, the old city centre, having lost its commercial vitality, has been taken over by a new type of commercial activity. It also reflects the overall situation in Turkey where preservation or restoration practices are not sufficiently developed, other than those carried out by specialists. Although it may at first appear that historical buildings are respected, and that the public possesses the knowledge that they are valuable as historical documents and it is necessary to protect them, this photograph can be seen as a regular memoir of a long period of insensitivity, showing that this initial perception is not reciprocated in practice. Murderous neglect of buildings, by abandoning them to their fate and the blows of time, is in fact quite widespread in Turkey.

Mehmet Atlı

3.

It could be said that this image of Hasan Paşa Hanı belongs to a postmodern period, when sensitivities regarding conservation and restoration were recognized by shopkeepers, city dwellers and social and bureaucratic-political platforms. The photograph marks a new phase, when the building has been restored and joined urban life with new functions, having also positively regenerated its historical aspect. It documents the fact that history, or historicity, can “make money”, or to be more optimistic, that the city has evolved in terms of its historical awareness. However, there is also a pessimistic aspect in the fact that the han has become an ordinary stop along tourist trails, a quick call-in for a souvenir photograph. And the same can be said for the loss of memory the building has experienced when what it had actually sought was to “remember, and make others remember, too”, and for the fuss and hurry brought on by this loss of memory.

Right beside the disciplined order brought on by the broad, unifying restoration practice, breakfast halls, cafés, jewellery stands, carpet shops that bring together the portraits of figures as diverse as Ahmad-i Khani, Ahmet Kaya, Deniz Gezmiş, Che, Said Nursî, Ayşe Şan and Yılmaz Güney also present a chaotic photograph of the city’s world of popular imagination.

Mehmet Atlı

(Photograph: Nevin Soyukaya, 2006)

The restoration of the han began in 2006, and both the public and related civil society organizations participated in the process. Or, in fact, they felt obliged to participate: Once the project began, complaints began to be made to the Diyarbakır Local Agenda 21 City Advisory Council’s Sub-Work Group for the Protection of Historical Texture. Following these complaints, a work group formed of specialists including architects, restoration specialists, archaeologists, construction engineers and art historians, carried out four separate examinations and prepared reports at Hasan Paşa Hanı until the restoration work was completed. Demanding the necessary improvements to the project, these reports were sent to relevant authorities and institutions including the Governorate, Ministry of Culture and Directorate General of Foundations.

Diyarbakır Yerel Gündem 21 Kent Danışma Meclisi (2006-2007) Hasan Paşa Hanı Restorasyon Çalışması ile İlgili Tespit Raporu 1-4.

The work group that had assembled to work on the restoration project of Hasan Paşa Hanı had documented perilous practices in its reports. For instance, in the southeast corner of the courtyard, a thirty-squaremeter area that did not exist in the original building had been created, and was covered with concrete. This area, which would have caused serious damage to the building, was cancelled after the first report.

Subsequent reports drew attention to other incongruent issues in the restoration project, from flooring to the roof structure, and from masonry work to door and window profiles. Public reaction, formed under the leadership of the City Assembly and civil society organizations, made sure that relevant institutions took these warnings into consideration, and a number of damaging implementations were cancelled. Although the unique architecture of the han is suffering today because of mistreatment, the intervention of the public in the restoration process back then did help Diyarbakır protect a part of its heritage.

Diyarbakır Yerel Gündem 21 Kent Danışma Meclisi (2006-2007) Hasan Paşa Hanı Restorasyon Çalışması ile İlgili Tespit Raporu 1-4.

Translation: Nazım Dikbaş