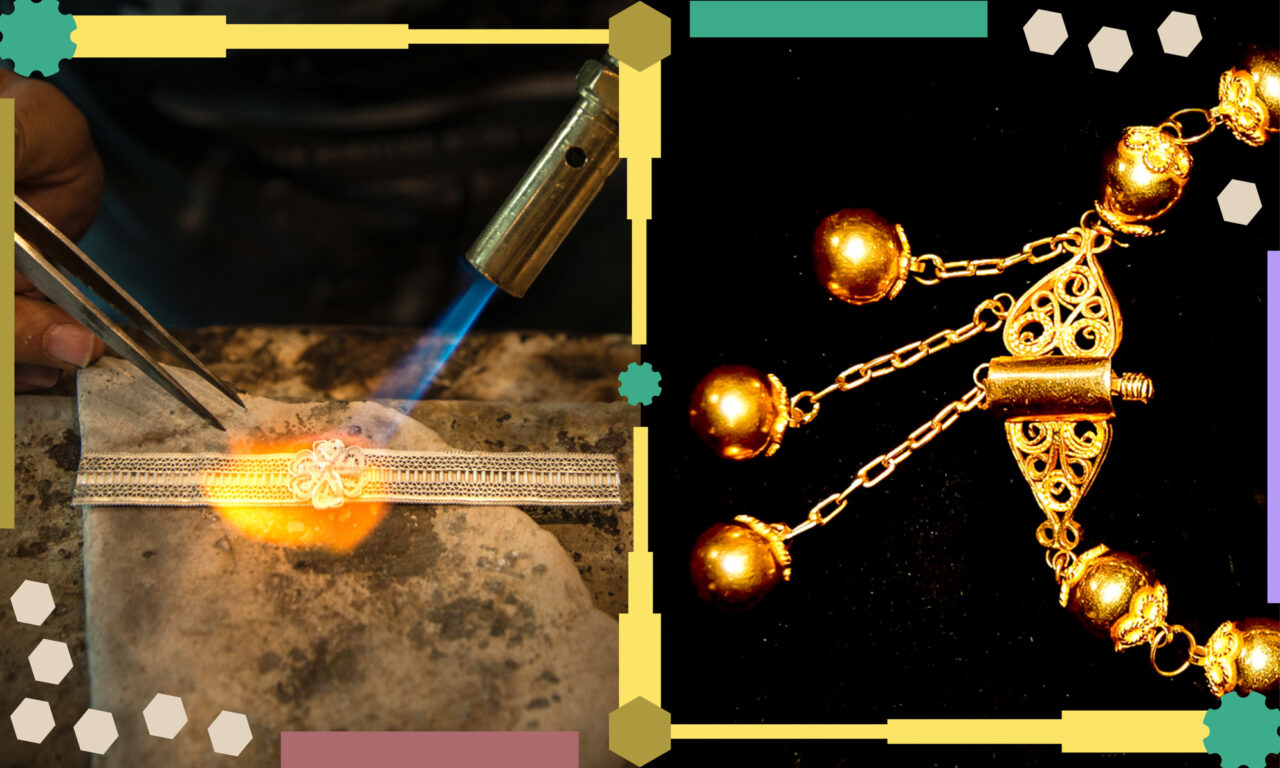

![What we know today about early human settlements tell us that Diyarbakır is located in an area where inhabitants always loved the occupation of adorning themselves, and that therefore, the art of jewellery developed immensely. The photograph shows the production of a silver <em>telkari</em> [a form of filigree] bracelet.](https://diyarbakirhafizasi.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/0_kuyumculuk-1280x854.jpg)

History tells us that Diyarbakır was, from its earliest settlements on, a place where people loved to wear ornaments and jewellery and adorn themselves. This interest meant that the craft developed in time, artisanship refined, products diversified and the city made a name for itself for its excellence in this field. The world and art of jewellery is not only a part of cultural wealth for Diyarbakır, but it was also an always-thriving commercial activity through the ages.

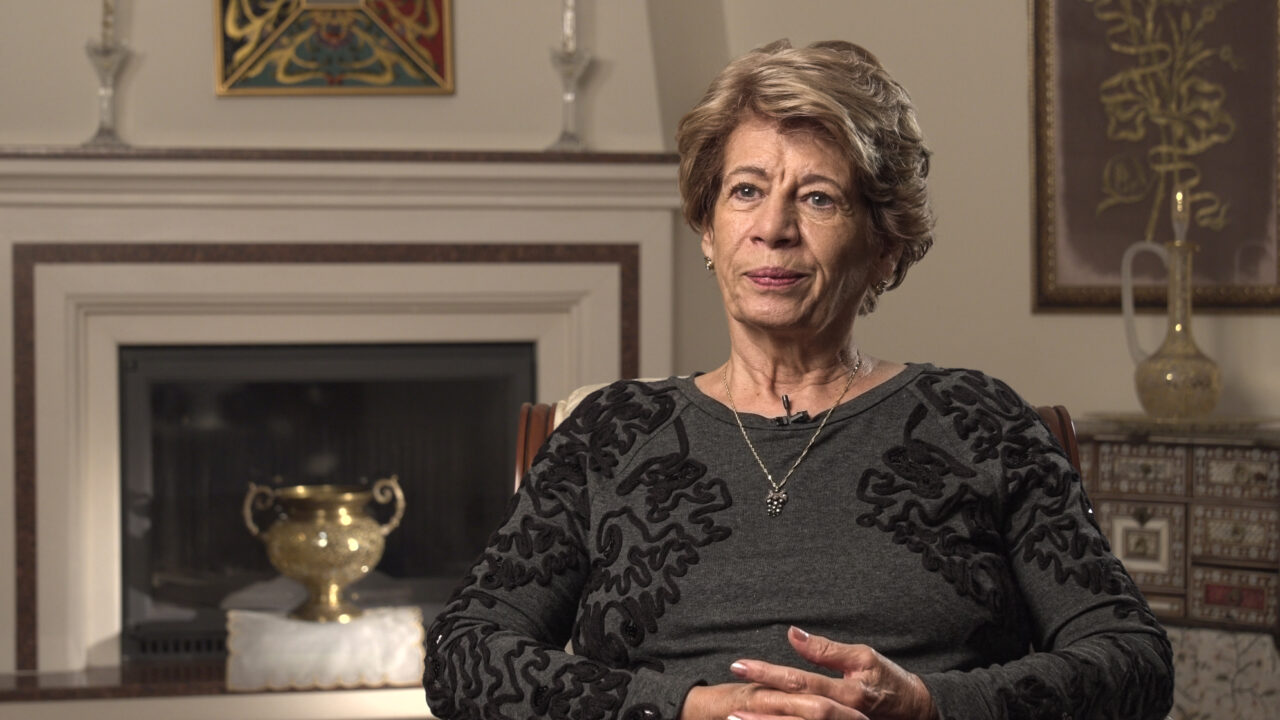

In this section, we wander from Çayönü to the British Museum and the markets of Diyarbakır and we look at the most preferred types of jewellery, the meanings they bear and how they are made. The story of master jeweller Yusuf Karadayı, beginning with his apprenticeship, sheds light on the adventure of jewellery in Diyarbakır and its transformation in recent years. Public health specialist Prof. Dr. Perran Ocak Toksöz, on the other hand, discusses how this craft finds a reflection within the home, as family heirlooms.

Archaeological remains of earliest human settlements reveal that the peoples that inhabited the lands that include present-day Diyarbakır were always fond of adorning themselves. We know that the first residents of Çayönü made jewellery using shells and soft stones they collected from freshwater sources nearby.

When the technical ability to shape stones improved over time, perforated beads with two or more holes were added to pieces of jewellery and harder materials like serpentinite, quartz and natural glass also began to be treated. Then, decoration and geometrical shapes on beads, grooved buttons and hoops were added to this. The discovery that when heated, pieces of copper could easily be shaped, led to the widespread production of jewellery with malachite beads.

Source: Nuri Durucu, “Diyarbakır Kuyumculuğu [Diyarbakır Jewellery]”, Diyarbakır Geleneksel El Sanatları [Traditional Handicrafts of Diyarbakır], Volume 2, Diyarbakır Valiliği, 2013.

An Artuqid belt in the British Museum collection is thought to have been made in the first half of the 13th century in Diyarbakır. Gold gilded on silver, the belt features compositions including both real and legendary creatures including eagles, hares, dogs, sphinxes and griffins, which are frequently used in many metallic works from the Seljuk era. The figure of the double-headed eagle with spread wings begins to appear in Anatolian Seljuk ornamentation from the late 12th century on and features throughout the 13th century. The same figure is present on coins minted in the name of Diyarbakır’s Artuqid rulers, Salih Nasîr al-Dîn Mahmud (1200-1222) and Mesoud Rukn al-Dîn Mawdud (1222-1231).

The belt exhibited at the British Museum emphasizes sovereignty through the inclusion of compositions representing the sun, light and illumination and therefore is believed to have belonged to a significant individual.

Source: Nuri Durucu, “Diyarbakır Kuyumculuğu [Diyarbakır Jewellery]”, Diyarbakır Geleneksel El Sanatları [Traditional Handicrafts of Diyarbakır], Volume 2, Diyarbakır Valiliği, 2013.

During the time of the Ottoman Empire, the jewellery of Diyarbakır held special renown. This was partly due to the fact that Ahmet Çelebi, a great master of this art who lived from 1539 to 1601 worked here. Ahmet Çelebi’s gold and silver works had even been praised by Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent in his oration. Selim II, too, who had come to the city as a prince, praised his craft and took many of his works with him back to the palace.

Ahmet Çelebi’s father was also a jeweller. He drew attention as a child with his amazing talent, and following his father’s death, he earned the title of master when he was only 25 years old. His fame, especially for his work with diamonds, had spread widely. The garden he landscaped in his prime with his students over a period of ten years was deemed unique in the manner that it brought nature and gemstones together, and the piece was later transported to Baghdad.

Source: Nuri Durucu, “Diyarbakır Kuyumculuğu [Diyarbakır Jewellery]”, Diyarbakır Geleneksel El Sanatları [Traditional Handicrafts of Diyarbakır], Volume 2, Diyarbakır Valiliği, 2013.

As this fame helped jewellery-making develop in Diyarbakır a safer structure was required, first and foremost to secure the various jewellery made or used in the trade. Gradually, the Jewellers’ Market and Hasan Paşa Hanı became production and trade centres where jewellers assembled, as recounted by travellers who visited the city after the 16th century.

According to Mehmet Salih Erpolat’s study “Osmanlı Dönemi’nde Diyarbakır’daki Esnaf Grupları ve Meslekler [Groups of Tradespeople and Professions in Diyarbakır in the Ottoman Era]” in the years 1568 and 1691, jewellery making is among the most widely practiced professions in the city.

Source: Nuri Durucu, “Diyarbakır Kuyumculuğu [Diyarbakır Jewellery]”, Diyarbakır Geleneksel El Sanatları [Traditional Handicrafts of Diyarbakır], Volume 2, Diyarbakır Valiliği, 2013.

Headpieces form a separate category among the traditional jewellery of Diyarbakır. Şırrık is a silver headpiece worn in the exact centre of the forehead. Eyyün is made by aligning gold coins on a piece of cloth, and this piece of cloth is tied around the head right above the eyebrows.

As for earrings, kişnişli küpe [lit. ‘earring with coriander seeds’] is among the most popular. Nose rings are made either from gold or silver. Wicker bracelets, kişnişli or habbeli necklaces or neckbands are types of jewellery identified with Diyarbakır. Cords, belts and halhal [bangles] are products that feature the subtleties of the region’s artisanship.

Silver jewellery known as hamaylı or boylama, in contrast with those mentioned above, are not visible from the outside. This triangular piece of jewellery holds verses from the Quran, is worn by women around their neck and under their clothes and is believed to protect from the evil eye and nightmares.

Men’s jewellery includes rings and watch chains. Pazıbent, or arm bands, may feature snake, scorpion or firearm motifs to protect from the evil eye. As with women, there are also varieties of hamaylı made for men to protect from evil and the evil eye.

Source: Nuri Durucu, “Diyarbakır Kuyumculuğu [Diyarbakır Jewellery]”, Diyarbakır Geleneksel El Sanatları [Traditional Handicrafts of Diyarbakır], Volume 2, Diyarbakır Valiliği, 2013.

![When one thinks of jewellery unique to Diyarbakır, necklaces and bracelets with habbe [lit. seed, kernel] (above) are among the first ornaments that come to mind. Another highly popular design is şırrık (below), a type of forehead jewellery. (Habbe photograph: Pelin Demirtaş Dikmen)](https://diyarbakirhafizasi.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/5c_kuyumculuk-960x1280.jpg)

“I was born in the courtyard of the Chaldean Church. My father moved from Midyat to Mardin and from there to Diyarbakır. At seven years of age, I went both to school and to the shop. It was about 1969-70 when my father took my hand and took me to a jewellery master. He told my master, ‘The flesh is yours, the bones are mine. However, there is something about Yusuf.’ What is it, my master asked. ‘My son is left-handed,’ said my father. My master answered: ‘It’s a sign of intelligence, I am left-handed, too, Master Antun. We will do our best, do not worry, we will train Yusuf’. There were seven or eight of us in that shop, we were friends, we got on very well with all of them. I would fear my master a lot when I was late to the shop. God knows, there were times when he gave us a beating. Godspeed to him, my master was short-tempered, and highly disciplined at work. Of course, if he didn’t beat us, we wouldn’t learn. I worked for twenty years in his shop. I was an apprentice, I became an undermaster, then I became a master. I am still practising my profession to this day. I love my profession very much. People pass away, but art does not. Knowing an art is like a golden bracelet. I had great ambition for our art, I mean, if you don’t love it, you can’t do it anyway.

My master trained three people from our family. He must have trained around forty, fifty people in total. Enver Yürük, born in 1941, he is alive. We owe him a debt of gratitude, he taught us an art. He was short-tempered, but he was a great artist. We were very poor. My father ran an off-license, and he also served as sexton for thirty years at the Chaldean Church. The Church helped us, they paid our electricity and water bills. Then I grew up, and since 1986, I have been president of the Church’s¹ foundation. Our church suffered some damage in the clashes that took place in 2015, it used to be active but it is in renovation now.

My master was Assyrian. Both Assyrians and Armenians were in the business. Tailors, jewellers, money changers, dentists, carpenters, these professions were all practiced by non-Muslims. Among the craftspeople there were Protestants, Assyrians, Ezidis and Jews. Now we continue, yet unfortunately nobody’s left in Diyarbakır. If they hadn’t left, Diyarbakır would have become Paris. I wish they hadn’t left.”

From the oral history study carried out by DKVD in 2021 with master jeweller Yusuf Karadayı

¹ Diyarbakır Mar Petyum Chaldean Church Foundation

“I have four daughters and a son. My son is in year 8, I am teaching him my profession. In the same way that I surpassed my master, he, too, will surpass me. I have taken notes since I was seven years old as my master taught me. That is the method I use to train my apprentices. I have trained more than 20 apprentices. They have their own shops, I am proud of all of them.

When we practised our profession in the 1970s, we didn’t have the machines, the tools, the technology. These days, jewellery making is easy. When we made kişnişli bracelets back then, we had to cut the coriander-seed-sized beads one by one by hand. You had to use manual strength, and our hands would swell. We would melt the gold with coal, now you have electricity, you have gas. Everything has become mechanized. We suffered a lot. We still follow my master’s path and do everything by hand. The training is not what it used to be. We came to our master to learn the art. Nowadays, they come for the money.

My master’s shop was on Aşefçiler.¹ My shop is in the jewellery market adjacent to the Historical Jewellery Market. That is where all the shops of non-Muslims are. The jewellery market now used to be the butchers’ market.

For instance, my master used to make kişnişli bracelets. Unique to Diyarbakır. The beads are like coriander balls. We used to forge them one by one, now we use moulds. Other than that? There is habbiye, there is direkli kolye [necklace with bars]. They are all telkari work, as my master showed us. Hasır bilezik [‘wicker bracelet’] is also unique to Diyarbakır, but we don’t make them. I also make prayer beads now. If I get an order for incili bilezik [bracelet with pearls] I make that, too.

It’s a craft that requires patience. You have to be proper, you have to be honest, you have to take your steps carefully. Of course, you can’t buy gold from everyone. Other than that? It’s a fine art, you need eyes for it. Now I have 7-8 eyewear prescription. I have been working for 52 years, my eyes are not what they used to be. Still, I manage, thank God, we do our best.”

From the oral history study carried out by DKVD in 2021 with master jeweller Yusuf Karadayı

¹ Aşefçiler/Ocak Street

![Master jeweller Yusuf Karadayı talks about what half a century has changed and has not been able to change in the production of bracelets known as “kişnişli [with coriander seed]” because of their beads the size of coriander seeds. (Photograph: Pelin Demirtaş Dikmen)](https://diyarbakirhafizasi.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/7_kuyumculuk-1280x610.jpg)

![The motif at the lock part where the two ends of the hasır [‘wicker’] bracelet meet is known as kaş [‘eyebrow’] and represents the sun rising between the mountains. (Photograph: Pelin Demirtaş Dikmen)](https://diyarbakirhafizasi.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/8_kuyumculuk-1280x540.jpg)

The making of the Diyarbakır wicker bracelet requires arduous and nuanced work. The work begins by preparing the gold wire with a diameter of 85, 95 or 100 micrometres. Then, the wire is wound around a rectangular malafa, or arbour, and cut, producing rectangular pieces with one end open. These pieces are interlaced, their open ends are welded, the wire is twisted with a pair of pliers and peened with a hammer on an anvil. Then the bracelet is peened again on the malafa to give it a bracelet form. Following these steps, the lock of the bracelet is adorned by hand. The pattern on the lock part that brings together the two ends of the wicker bracelet and known as kaş [‘eyebrow’] in the region, is a distinctive characteristic of the bracelet. This kaş pattern represents the sun rising between the mountains.

Source: Derya Şahin and M. Meral Yağçı, “Diyarbakır geleneksel el sanatlarımızdan hasır bilezik üzerine incelemeler [Studies on hasır bilezik {wicker bracelet}, a traditional handicraft product of Diyarbakır]”.

A characteristic feature that sets the Diyarbakır wicker bracelet apart from others, is that the gold wire used is not 25 micrometres in diameter as in Trabzon wicker bracelets but thicker, 85-95 or 100 micrometres. The Diyarbakır wicker bracelet is stitched with a zigzag appearance while the Trabzon wicker bracelet is flat. Another difference between the two styles is the tradition of adding a chain to the lock part of the bracelet in order to add a Reşat altını, a gold coin minted for Sultan Mehmed V Reşad.

All wicker bracelets are handmade and only the weaving of the gold wire takes four hours. Another two hours is spent making the lock. 18 or 22 carat gold is generally preferred. Another difference between the two styles is that the gold weaving is done by women in Trabzon and by men in Diyarbakır.

The thinner wicker bracelets are worn by young women while thicker wicker bracelets are worn by married women. It is a custom to gift these bracelets to brides at weddings, and unless there is great financial hardship, it is not deemed appropriate to sell them on.

Source: Derya Şahin and M. Meral Yağçı, “Diyarbakır geleneksel el sanatlarımızdan hasır bilezik üzerine incelemeler [Studies on hasır bilezik {wicker bracelet}, a traditional handicraft product of Diyarbakır]”.

“Many Armenian and Assyrian families left Diyarbakır. Diyarbakır culture acquired a lot from them, they were all great artists. For instance, the Armenians and Assyrians were the best in jewellery. In the 1600s, the silverwork and ornaments made by Ahmet Çelebi captured the attention of governor Hasan Paşa, and the governor thinks, ‘this art exists in this region, let’s help develop it’ and orders the construction of a Kuyumcular Hanı, a commercial building for jewellers. The structure today known as Hasan Paşa Hanı was in fact a market built for jewellers. Both in terms of the cutting of diamonds and emeralds and the silverwork were highly esteemed. Diyarbakır jewellers always competed with the jewellers of Istanbul. At times, the masters in Diyarbakır surpassed the masters in Istanbul in terms of mounting, cutting and the end product. The silver gate of the mausoleum of Rumi in Konya was made entirely by Diyarbakır silversmiths. And also the gold- and silver-gilded gate of the tomb of Imam al-Azam [Abu Hanifa] in Baghdad.

This artistic style is reflected in the ornaments and jewellery the women of Diyarbakır wear, and in the accessories they use in their homes. For instance, they used to be called peştahta in the past, the silverwork of these drawers is completely unique to Diyarbakır. The gülabdan, the elegant rose water flasks, used during mevlit, memorial services, and also the buhurdan, thuribles, each one a work of art… The nalın, the wooden clogs women wore in the public baths…

I remember how my late mother told us that our grandfathers were also highly talented in this work. They used to draw the setting and direct the master jeweller in how to proceed, thus resulting in unique examples of jewellery. The jewellery we have as family heirloom are all like this, their setting was designed with the contribution of our grandfathers, they are special examples of jewellery.”