Moments when life begins, or comes to an end with the last breath find social meaning expressed in a series of rituals that vary according to religions and cultures. Cities like Diyarbakır where, throughout history, identities have intersected, allow us to observe how such different traditions have come into contact with and even influenced each other.

Researcher and writer Birsen İnal wrote about birth and death rituals of Islamic origin in Diyarbakır. The mostly intertwined Assyrian and Armenian rituals were examined by researcher Mehmet Şimşek. Art historian Birgül Açıkyıldız focused on Yezidi faith traditions from the cradle to the grave, extending onto beliefs about the after life, all enriching the exhibition with their contributions.

In the past, in Diyarbekir, if the midwife did not state after the first examination that it would be a difficult birth and that the mother should give birth in hospital, all births would take place at home. Capable midwives were quite famous and included Melahat Ebe, Satberg Ebe, Bahtiyar Ebe, Mecbure Ebe, Kıbrıslı Ebe and Adalet Ebe – who was midwife to around eighty percent of the population of the Bağlar, Peyas and Yeniköy districts. There were also uncertified lay midwives, known as neighbourhood midwives.

Even when there weren’t many taxi cabs in the city, the family would find a way to hire a taxi to pick up the midwife. Before that, the midwife would be taken by horse carriage from her home. Following the birth, hearing the first cry of the baby, relatives in the house would fill the room with joy and shower the severed umbilical cord with baksheesh. The amount of baksheesh would change depending whether the baby was male or female. The capable midwife would fold the umbilical cord in two and tie it tightly with a piece of string. Since every midwife was not equally capable of performing the tying the umbilical cord, folk would condemn midwives who failed to do their job properly. If the baby was a girl, her umbilical cord would be placed in the drawer of the sewing machine or the dowry chest so she became skilful and home-loving. If the baby was a boy, his umbilical cord would be buried in the garden of the madrasa or the school so he became a scholar. If the family wanted the baby to become an artisan, the umbilical cord would be hidden in the shop of an artisan by the grandfather or father.

The midwife would give the baby its first bath and then wrap it properly in swaddling clothes. Headdress known as “şübara” would be placed on the baby’s head, and its forehead would be tightly wrapped with a triangular gauze to prevent frontal bossing. Finally, a white calico apron, featuring the words, “Show your love but do not kiss” written in herringbone stitch would be fitted onto the baby to finish the swaddling process.

Birsen İnal, Researcher, Writer

The new mother would be given gruel with molasses or “kayganağ” (omelette with molasses) to increase her strength and blood flow, and she would be asked to repeat, three times, the rhyme “Bulamaç bulamaç ağzım dolî, qarnım aç [‘Gruel gruel, I am hungry and my mouth is full”]. The nefse (postpartum mother) would not be given anything cold to eat or drink, she would be dressed in a blue dressing gown to fend off the evil eye, and she would be given a blue headscarf to wear.

When the father enters the room in which the birth took place for the first time, the paternal grandmother would pretend to weigh the baby in her two hands and ask the father, three times, “Who weighs more, you or the baby?” The father would then answer, all three times, “The baby weighs more”, and then kiss the baby on the forehead. Nothing would be given to the baby until the adhan was sung three times into its ear, and after three adhans, if the name had already been determined, either the grandfather or the uncle whispered the name of the baby into its ear, and thus the baby was named. A person known to be softly spoken and mild natured would rub some honey on the lips of the baby with his or her finger. According to tradition, the baby would then become softly spoken and mild natured, and the honey would also help the baby pass its first stool.

The first few drops of the mother’s first milk, known as “ağuz” would be sprinkled somewhere where no feet will tread, and then the mother would breastfeed the baby. A dry onion would be chopped and rubbed on the mother’s nipple after the breastfeeding to prevent it from cracking.

Nefselik (the postpartum period) was a challenging time for women. Since the toilet, bath and kitchen of old houses were outside the main building, new mothers could get seriously ill if they did not take sufficient care. The evil eye was also frequently mentioned during this period. The old saying went, “Nefsenin mezeri kırx güne qeder açıxtır [‘The new mother’s grave remains open for forty days’]”. Therefore, the mother would be carefully protected during the postpartum period.

The baby’s face would not be left open, a blue or pink regional silk cover with needlepoint embroidery would cover its face. Newborn jaundice seen during the first week of birth was known as “reng değişimi”, a change in colour, and the baby’s face would be covered with a yellow sheet until the jaundice passed, and the father would pin a golden ‘Maşallah’ coin on the shoulder of the baby’s dress. Everyone who saw the baby would then say “Maşallah”, and if anyone forgot, they would be reminded to say so. The new mother would keep a quilting needle on the chest of her clothes, and always carried a small jack-knife when she went to the bathroom. It was believed that sharp objects protected us from the “eyi” and the “uç hurflî” [ghosts and demons]. It was for this same reason that a knife, a pair of scissors and a small Koran would be left by the side of the baby’s bed, and a piece of bread in between the baby’s swaddle.

Birsen İnal

On the baby’s seventh day, the “seventh night” ritual would be held. Close relatives and neighbours would be invited, a mevlit recital would be held, and this was followed by a night of entertainment to celebrate the baby’s birth. The Seventh Night was an opportunity for those who could not visit the baby and the parents and present gifts until then. Women would hold their own entertainment, play darbuka [goblet], oud and tambourine, and dance. The baby would be passed from lap to lap and lullabies, tongue twisters and songs in Turkish, Kurdish, Zazaki, Syriac, Armenian and Arabic would be told and sung.

Depending on the financial situation of the family, the seventh night would be held ‘savoury’ or ‘sweet’. If it were to be ‘savoury’ then main courses including duvaklı pilav [‘shrouded’ pilaf], ekşili dolma [sour stuffed leaves], meftune with aubergines or courgettes, depending on the season, su böreği [a pastry dish], zerde [a saffron and rice dessert] and sargı burma [a dessert similar to baklava] would be prepared in the daytime, or tel kadayıf [shredded wheat in syrup] with walnuts and butter would be crisply fried on the barbecue. If it were to be held ‘savoury’ then it was again the financial situation that determined preparations. Akide şekeri [a type of hard candy] was for the wealthy. If the financial situation of the family wasn’t well, then cones made of old newspaper or notebook pages would be filled with the cheaper Antep candy, and a single Turkish delight, and lined up on trays. Biscuits would be left in the middle of the tray, the tray would be covered with “qademe boxça” (a satin or velvet bundle, embroidered with golden or silver lining) and placed in the middle of the room, on top of a small bench. Sometimes homemade çörek [a type of tea cake] would be served instead of biscuits. Red nefse sherbet with cloves and cinnamon was a must on seventh night ceremonies.

The baby would be washed, swaddled and prayers against the evil eye would be said as it was placed into the embroidered crib. The new mother would wear all the gold she had, and sit in her bed like a queen. In some ceremonies, the hands and feet of the new mother would be dyed with henna.

The seventh night ceremony was a tradition, a religious ceremony designed to say “welcome, baby, into this world”. Quite probably, it was a ritual that had continued since the times when all tribes lived together. After all, our Christian neighbours would baptise their babies at church on the eighth day of birth with a similar set of rituals.

Birsen İnal

In old Diyarbekir many customs related to qırx (kırk çıkarma) constituted precautionary measures against potential health problems, even if their benefits were unknown. The fear of the pir’ebok,¹ said to haunt and pester the qırxlî, or women within the forty days of the postpartum period, meant that the baby and the mother would never be left alone within those forty days. Any two qırxlî women would try not to meet, and if they did, they would exchange the quilting needles they carried on their chest. A qırxlî woman would not attend funerals, and in cases where she had to, she would wash her face and hands with the funeral water so the pain of losing a close loved one dampened before its fire burned her heart.

In almost every household there would be qırx, or fortieth day bowls, brought back from the hajj pilgrimage. The qırx water would be poured from these bowls. The fortieth day, was the day when the life-threatening danger was averted and evil spirits were cast away both for mother and baby, and metaphorically, the day when ‘the grave was closed’ for the puerperal mother. Although it was known as the fortieth day ritual, it would be held on odd-numbered-days, either on the 39th or the 41st day after birth. The person who was to carry out the qırx ceremony had to be a religiously observant person.

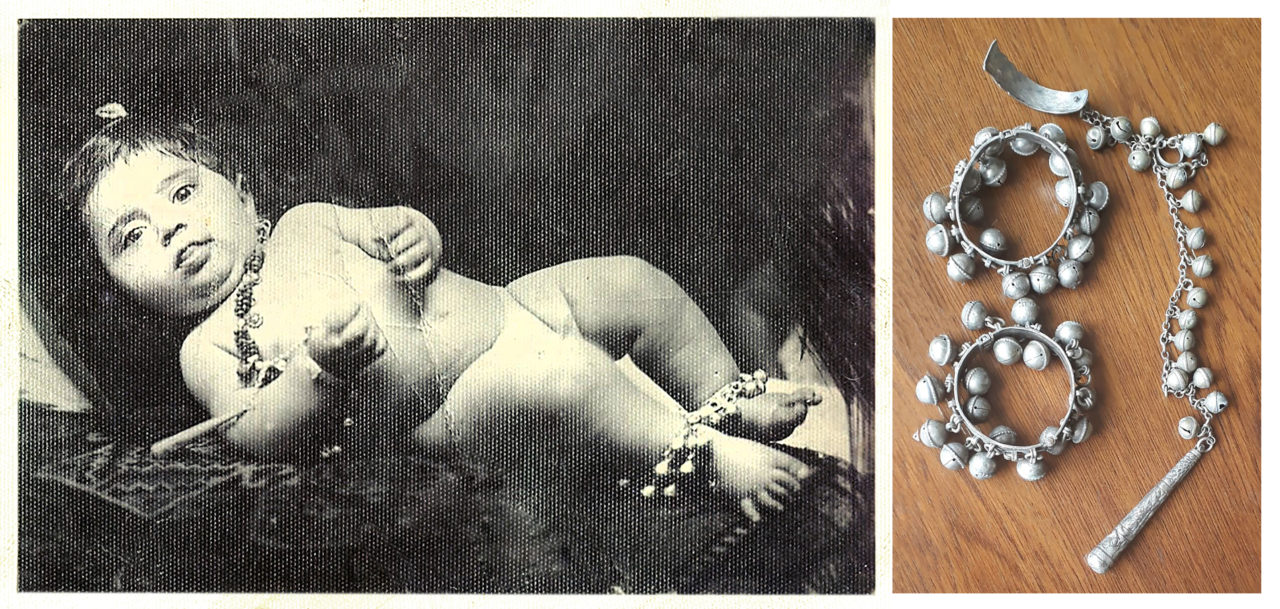

If there was a bathroom in the home, then there, if not, then in a room, first the baby, then the mother would be given the meticulous ritual wash in a teştin (washbasin) accompanied by prayers. An ivory comb with forty teeth, a tespih with ninety-nine prayer beads, forty small stones, rose petals and metal coins would be placed in the qırx tasî [‘bowl of the forty days’]. The person in charge of the ceremony would prepare the water for the forty days by reciting the Kelime-i Şahadet prayer three times, the ‘Elham’ surah once and then the ‘İhlâs’ surah three times into the water filled into the bowl, then the water would be sieved with a strainer or a filter. The woman in charge of the ceremony would stretch out the fingers of her right hand like a comb, dip it into this water, and by saying “Qış qış, qırx qaç, ben geldim!” [‘Be expelled, run you forty, I am here!’] would sprinkle the water across all corners of the room. Then the words “Birler, üçler, yediler qırxlar şahidim olsun ki bebeğimizin qırxî çıxtî!” [‘May the ones, the threes, the sevens and the forties (spirits) bear witness that the qırx of our baby has finished!’] would be said and the baby and mother would be given a long ritual cleansing.

After the ceremony is complete and before the baby is breastfed, a few drops of its mother’s milk would be dripped into the baby’s mouth, saying “Emelî salêh ola” [“May its deeds be pure”] and then it would be breastfed.

The babies nails would be cut for the first time only after the fortieth day. Before the nails were cut, the baby’s right hand would be dipped into its father’s right pocket, and the first note of money the baby grasped would be given to the poor as “dırnax sadaqasî”, the ‘alms of the nail’.

Birsen İnal

¹ A female jinn/creature. Pir’ebok is believed to live by the water, to be afraid of sharp objects because it has long hair and long fingernails. Since it is also believed that it chooses to haunt and pester new mothers, precautions are taken for the first forty days after birth. A safety pin is attached to the mother’s collar and the baby’s swaddle, and sharp objects are placed under their pillows.

An upcoming birth is a source of excitement and reason to take action not only for parents but also other family members in the Ancient Assyrian community. The birth takes place at home. Experienced elder women act as midwives. Men are not allowed to be in the home during birth. If the birth is successful and the child is a boy, in the past, the happiness was often greater. Among Diyarbakır Armenians, the tradition is to say “Woman, may you go blind, it’s another girl” when the baby is a girl, yet “Woman, congratulations, you have given birth to a boy with a head as big as a watermelon” when the baby is a boy. A Bible is left by the side of the newly born baby and the mother’s bed, and metal objects like scissors and a hairpin are placed under their pillow.

Midwives do not demand a fee for this work, but they are always given certain presents known as “midwives’ gifts”. The legs of newly born babies are closed before they are swaddled (khındağt). The baptism of the baby is generally held at church on the eighth day following birth. As in Assyrians, the Armenians do not demonstrate love towards children after birth, because the child has been born with the original sin. The baby is not kissed until the end of the seventh day when the baptism is held. The mother, too, like the child, is considered stained, and she is not allowed to touch objects other than those exclusively reserved for here. With the baptism held on the eighth day, the child is considered purified, however, the mother cannot touch holy objects or enter the church for forty days. At baptism ceremonies held at churches or monasteries, a naming prayer is said for the baby. The baby that is cleansed of original sin becomes a permanent member of the community.

Mehmet Şimşek, Researcher, Writer

For Diyarbakır Armenians, the most important part of the baptism ceremony is the naming of the child. The child is generally named by the godfather, and then the child would be registered in the church book. Children whose father was not known were registered as “a child of the church”.

In the Assyrian Church, baptism is carried out by immersing the child in water. The baptism ceremony is held a week after birth, at the earliest opportunity. Every child must have a godfather.¹ The kirve repents, swears oath and participates in prayer on behalf of the child. The kirve must be Christian. A person can act as kirve for more than one person. The child is dipped three times into blessed and consecrated water, and anointed with chrism and myrrh. The kirve recites the prayers on behalf of the child.

The baptized child is given the name of a saint so that she or he is protected by her or him. If the child is male, then he is taken to the church’s altar, and dedicated to god; however, girl children are not taken to the altar. The child in the lap of the kirve is taken around the altar (kduşkudşin) three times, and at every round the kirve kisses the Bible. Meanwhile, a spoon is first touched upon the communion tray and the wine cup, and then touched upon the lips of the baptized child.

The general understanding of the concept of kirve in Muslim tradition, and the concept of kirve in the Assyrian community are different. There is no religious basis for the concept of kirve in Muslim tradition. However, through cultural interaction, it has assumed a meaning close to that of the Assyrians, and has been practiced in this way (there can be no marriage with the daughter of the kirve). Assyrians in Diyarbakır would prefer to establish a kirve-relationship with their Muslim neighbours. This also served to prevent interreligious marriages.

Mehmet Şimşek

¹ Godfather/kirve in Syriac: şavşbino, karibo, mhadyono. Godfather in Armenian: gınkahayr. Godmother in Armenian: gınkamayr.

According to the Yezidi faith, for someone to be accepted as an Yezidi, both her or his mother and father must be Yezidi. Therefore, marriages are endogamous, and also abide by caste rules. In addition to this obligation related to marriage, an Yezidi must also take part in various ceremonies, from birth to death, to be accepted as a part of Yezidi society. Many of these rituals take place during the stage immediately after birth, for instance the haircut (biska pora) and circumcision (sinet) ceremonies for boys, and baptism (mor kirin) and afterlife sibling (biraye/xuşka axrete) selection ceremonies for both boys and girls… The funeral (mirin) ceremony, in the Yezidi faith, symbolizes the end of this life, and the beginning of a new one.

Biska pora is a type of baptism, and only for male children. Until the biska pora ritual is realized, often carried out in the home of the child’s family, the child’s hair is not cut. In the past, this baptism ceremony was held when the child reached its fortieth day, but today it is held between the sixth month and the first birthday by contemporary Yezidis. For every male child, two ‘afterlife brothers’ must be selected, one from a pîr family, and the other from a şeyh (sheikh) family. These brothers will help guide and protect the child. For the female child, ‘afterlife siblings’ can also be elected from among female pîrs and şeyhs. During the biska pora ritual, the child’s forelock is cut by one of his afterlife siblings, accompanied by prayers. After the ceremony, the forelock is kept by the child’s family, or it can also be given into the protection of his şeyh or pîr. This is followed by the presentation of gifts and monetary donations by the child’s family to its afterlife siblings.

Associate Professor Birgül Açıkyıldız, Art historian

The baptism ceremony, known as mor kirin, can only be held at the Kaniya Spi baptisery at Lalish [the holiest temple of Yezidis in Ninawa, Iraq]. However, since Yezidis live in different countries for a variety of reasons and therefore cannot always go to Lalish, holy water brought from Lalish can be used to carry out the baptism ceremony wherever they happen to be. The ceremony is conducted by a şeyh, or a mücavir at Laleş, or a pîr that serves as a “protector”, and in the presence of only the child’s family. The mücavir takes some water from a natural spring in Kaniya Spi and sprinkles it, three times, on the head of the child, meanwhile singing Kurdish hymns: “Ho, hola, Êzî Siltan. Tu buyî berxê Êzî, serekê riya Êzî”.¹ Then the child is declared a servant of Ezî. After the baptism ceremony, the child’s parents present money and gifts to the mücavir. Ideally, the mor kirin ceremony is held when the child is very young, however, if this is not possible, it can be held at any other stage of life.

Male children are circumcised twenty days after their baptism ceremony. The mother and father of the child appoint a kirve (kerif) for the sünnet (circumcision) ceremony. The bond established by becoming a kirve is considered to be as strong as a blood tie. Therefore, no marriage can be held between the two families for seven generations. This is also the reason why a kirve is selected from either a different caste in society with which marriage is already impossible, or from Muslim families. The circumcision ceremony is held at the child’s home. After the circumcision is carried out, the family holds a feast, and dances are initiated in celebration. Yezidis living in Armenia today cannot realize this ritual because they live in a Christian environment. Since according to the faith, if an Yezidi dies without being circumcised he is considered an infidel, and will be punished during the posthumous migration of the soul, uncircumcised Yezidi men are circumcised immediately before they are buried.

Birgül Açıkyıldız

¹ “Ho, hola, Ezi Sultan. You have become the lamb of Ezi, the head of the Ezi faith.”

In Diyarbekir, the city of tribes, as the peoples living together and side by side, our faiths may have been different, but from birth to death, many of our customs and traditions displayed common traits. In old Diyarbekir, after the body of the deceased was washed, the cauldrons in which water was heated would be turned over, just like Christians did. If the deceased had willed so, the corpse washer would be given the ring or the earrings of the deceased, and if there was no will, a certain amount of money, and a set of towels belonging to the deceased would also be presented to the corpse washer. The shroud would be cut out with a knife, and the thread would not be knotted after it was sewn. The tradition of ‘devir’ is practiced, and the hodja who conducts the practice is paid. For this reason, our elders were not only prepared for death in the spiritual sense, but always in the material sense as well.

After the funeral procession left the house, the shoes of the deceased would be left in front of the house, and her or his clothes would be given away. Some halva would immediately be fried and distributed. There would be no cooking in the mourning house. Neighbours and relatives would cook at their own homes, serve it themselves and do the washing up. There was always strong solidarity, both in good times and bad. The men would sit three days and the women seven days in the mourning house. Every person who entered the house would say “Lillahi Fatiha”, open their hands, and recite the Fatihah surah along with the entire community. Worry beads would be counted and the count would be recorded with chickpea seeds. These chickpea seeds would then be taken to the cemetery on the seventh day visit and planted in the grave. According to the belief, as these seeds grow and sprout, and blow around in the wind, the sins of the deceased are forgiven. On the seventh day, the mevlit and tesbihat prayers are said, and halva and warm bread is distributed to the entire neighbourhood. After the seventh day, the family of the deceased would wash and change their clothes. The clothes they wore for the first seven days would be washed by their neighbours, thus marking the end of the mourning period.

During the mourning period neighbours would not do any washing either, and even if they had to, they would dry it behind closed doors and not hang it out in the open. The radio would not be turned on, and all entertainment activities would be cancelled. On the fortieth day, a mevlit recital with dinner would be held to feed the poor. On the fifty-second night, after the night adhan, a few people would accompany the hodja to the head of the grave to recite the fifty-second night prayer. According to belief, it is on the fifty-second night that the bones are separated. The prayer recited would help relieve the pain of the deceased as this took place.

Birsen İnal

Assyrians see death as the head of a bridge extending towards eternal life, and the end point of earthly suffering. Those who have faith in Jesus Christ and live a devout life believe they will attain well-being and safety after this transitory world full of difficulties, pain and suffering.

The deceased’s arms are crossed atop her or his chest, her or his face is turned towards the East and a cross is placed between her or his fingers. The Bible is read by her or his side, and a candle is lit at head and feet level. A metal object, for instance a pair of scissors is placed on the body. Clergymen, hearing of the news of death, ring the church bells three times with short intervals.

The pastor or the priest recites a prayer and lights incense when he comes to the house where the deceased is. The loved ones of the deceased begin to gather. After the body is taken out of the house, the bed is made and a stone that fits into the palm of a hand is left on the bed. Wealthy families give away the bed, and the clothes of the deceased to the poor.

Assyrian clergymen that have attained the rank of diviner do not attend work such as the washing and shrouding of the corpse. This work is more often done by deacons or experienced, elder members of the congregation. If the deceased is a woman, her hair is braided in one or two plaits known as the “braid of the dead”, and covered with an embroidered headscarf. The body is washed, dressed in clean clothes and shrouded in white cloth. If the deceased is of marriage age, or engaged, the body is dressed in a wedding gown or groom’s suit.

After the deceased is shrouded, he or she is covered with a one-metre-long cover-cloth brought from Jerusalem, featuring the image of Christ surrounded by crosses. A piece of bread is placed under the head of the deceased, believing it will make it lighter, and easier to carry.

The face is left visible in the coffin, and the coffin is placed in front of the altar. Then, the funeral mass, which lasts around an hour and a half, is commenced by the clergymen and their assistants. The traditional ululation (tilili) is performed especially if the deceased was young, as the coffin is taken out of the church, and a single ring of the church bell is heard. The funeral procession, led by the clergyman, heads towards the cemetery.

Mehmet Şimşek

Assyrian cemeteries are in the courtyards of monasteries or churches generally built outside residential areas. Saints, patriarchs, bishops and other important figures are buried either in a location close to or in the courtyards of these temples. There is an Assyrian cemetery close to Urfakapı in Diyarbakır. For a long time now this cemetery has been used jointly by the Assyrian and Armenian communities.

After the interment, the clergyman and relatives of the deceased accept condolences at the cemetery gates. Either bread and halva, or biscuits and Turkish delight (lahmo raha) is offered to those attending the funeral. Then the procession collectively moves on to the house of mourning.

No food is brought to the house of mourning from the outside. If the deceased has no kirve (godfather, godmother or their children), then members of her or his family prepare food and offer it to those present. In Assyrian tradition, food is distributed on the third, ninth, fortieth days of the passing, and on anniversaries. Today, the fifteenth day has also been added to these significant days.

Mehmet Şimşek

Armenians believe that the flight of the spirit to heaven takes seven days, so on the seventh day after the passing of a person, specific prayers are recited. The deceased is believed to feel hunger and thirst for a period after death, so a common memorial luncheon known as “Hokejash/Hokehts” is held in her or his memory. Until a year is gone by following the passing of the loved one, food is served to relatives and neighbours every Friday night. This is believed to be the share of the person who lost her or his life. On the fifteenth day, halva is offered.

Cemetery visits are held on Saturday evenings, on feast days and on the second day of Easter. Incense and candles are lit on the graveside. On the day described as The Sunday of the Dead on the Assyrian church calendar, a general service is held for all those who have passed away since Adam and Eve.

Assyrians mourn for three to seven days. Condolences are accepted either at the home of the deceased or in church halls, accompanied by clergymen. Cleaning at the mourning house is carried out by the same person for the three days. During the mourning period, men don’t shave, no one washes and no washing is done in the house. Women of the mourning family wear their headscarves inside out. Bitter coffee is presented to those who visit to offer their condolences. The clergyman responsible of the congregation remains at the mourning house throughout the period of condolences, and does not leave if he is not obliged to. Prayers are recited by the clergyman.

Gravestones are placed at the head and foot of the grave, and are made from concrete or mosaic, and are curved at the head and the middle. Water and grains are placed in the curved parts. A while later, the tombstone is placed at the grave.

Mehmet Şimşek

Yezidis believe in Heaven and Hell, and reincarnation. Death is the departure of the soul from the body and its rebirth in another body. After Judgment Day, the soul reappears in another body, and does not remember its past life. Therefore, it is not responsible of its past sins; and thanks to its intellect it is able to establish a new life on earth.

The funeral ceremonies of the Yezidis display some differences according to region, however, their customs are common to a great extent. The afterlife siblings of the deceased, the sheikh and pîr, must accompany the funeral ceremony. After the corpse is washed by the sheikh or pîr, it is wrapped in a white shroud (kifin), tied at the head and placed in the coffin. A fistful of holy soil, brought from the Sheikh Adi Temple in Lalish, and squeezed into a small ball (berat), is placed in the mouth of the deceased.

A procession heads to the cemetery, accompanied by hymns, and led by a group of clergymen. If the deceased is a child or young person, the ritual may also feature music played with kaval, flute and tambourine. The coffin is lowered into a pit prepared beforehand. The head of the deceased is turned to face the east. Women cry, pull their hair out and beat their chest as they mourn. Those who take part in the funeral visit other graves as well. On the same day, a great common meal is held for the community.

After the funeral, when the land is dark, the family of the dead asks the koçek, a religious soothsayer, what the fate of the dead person will be. The koçek silently focuses, begins to tremble, then experiences painful convulsions and finally enters into a trance. Then he begins to recite what he has seen. If the deceased is a sinner, the koçek says that his/her spirit has entered the body of a dog, a donkey, a pig or a similar animal. On the other hand, if the koçek says, “Stop your crying, I have seen her/him. S/he has entered the body of one of our people”, then everyone calms down, and the family of the deceased finds comfort. Three days after the passing, the family holds a great dinner in memory of the spirit of the deceased. Every day for a week, the afterlife sibling of the deceased visits the family home, recites hymns (qewl) and praises the deceased to console the family. On the fortieth day, an animal is sacrificed at the head of the grave and its meat is distributed to passers-by as alms.

Birgül Açıkyıldız

Translation: Nazım Dikbaş

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Birsen İnal

• İnal, B. (2013) Özümsen Diyarbekir, Lîs Yayınevi, Diyarbakır.

Mehmet Şimşek

• Adam, S. (2015) “Anadolu Ermenilerin Adet ve Geleneklerine Genel Bir Bakış [A General Overview of the Customs and Traditions of Anatolian Armenians]”, Lousavor Avedis.

• Dikmen, A. (2015) “Değişik Din ve Mezhep Müntesiplerinin Ölümle Gelen Sosyal Birliktelik Algıları ve Ölümü İçselleştirme Uygulamaları (Diyarbakır Örneği) [Perceptions of Social Togetherness Awoken with the Event of Death in Members of Different Religions and Denominations and Their Practices of Internalizing Death (The Case of Diyarbakır)]”, Uluslararası Sosyal Araştırmalar Dergisi [International Journal of Social Research], 8(40): 460.

• Ertaş, K. (2014) Sosyo-Kültürel Açıdan 19. Yüzyıl Diyarbakır Ermenileri [19th Century Diyarbakır Armenians from a Socio-Cultural Viewpoint], PhD Thesis, Marmara University Institute of Social Sciences, Istanbul: 72-77.

• Grant, A. (1994) Nesturiler ya da Kayıp Boylar [The Nestorians, Or, The Lost Tribes,], translated into Turkish by Meral Barış, Nsibin Yayınevi: 73.

• Günel, A. (1970) Türk Süryaniler Tarihi [History of Turkish Assyrians], Istanbul: 325.

• Küçük, A. and Tümer, G. (1993) Dinler Tarihi [History of Religions], Ocak Yayınları, Ankara: 297.

• Lalayan, E. A. (1914) Van Bölgesindeki Asurlular [Assyrians of the Van District During the Rule of Ottoman Turks], çev. E. İhsan Polat, Tbilisi: 68-71.

• Öztürk, L. (1998) İslam Dünyasında Hıristiyanlar [Christians in the World of Islam], İz Yayınları, Istanbul: 1998.

• Segal, J. B. (2002) Edessa (Urfa): Kutsal Şehir [Edessa, ‘The Blessed City’], Translated by Ahmet Arslan, İletişim Yayınları, Istanbul.

Birgül Açıkyıldız

• Açıkyıldız, B. (2010) The Yezidis: The History of a Community, Culture and Religion, I.B. Tauris, London and New York: 99-103.

• Lescot, R. (1938) Enquête sur les Yézidis de Syrie et du Djebel Sindjâr, Beirut: 148-157.

• Suvari, C. (2013) Ezidiler: Etno-Dinsel Bir İnanç Olarak Ezidilik [Yezidis: Yezidism as a Ethno-Religious Faith, Ütopya Yayınevi, Ankara.

• Yalkut, S. B. (2014) Melek Tavus’un Halkı Ezidiler [Das Volk des Engel Pfau: Die Eziden], çev. Sabir Yücesoy, Metis, İstanbul: 66-72.

• Author’s notes from interviews with Yezidis, taken in the period from 2001 to 2005.

![The difficult postpartum period would end with the ceremony known as “kırk çıkarma” [‘the end of the forty days’]. Here, a “kırk tası” [‘bowl of the forty days’], found in every household and often brought from the hajj pilgrimage would be used to wash the mother and baby.](https://diyarbakirhafizasi.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/4_Dogum-Olum_e-1280x984.jpg)