When we speak of Diyarbakır’s social and cultural life, it can seem as if the diversity composed of beliefs, ethnic identities and languages is an aspect of the city which has now been confined to the annals of history. Anthropologist Suavi Aydın begins this exhibition by looking at the depth of this cosmopolitism in its historicity. Aydın investigates the roots of “Diyarbekirlilik”, the unique character of being from Diyarbekir, a city that managed to retain its accumulated qualities that go back to antiquity until the early 20th century, and in this sense, resembles Aleppo, 18th century Ankara or late-19th century İzmir. Then we will look, from Diyarbekir to Diyarbakır, at rituals of birth and death, music, gastronomic culture and wedding traditions that have stood side by side, co-existing, mixing, nurturing one another. We will focus on the culture of hamam, or public baths, and the adventure of entertainment in the city, from coffee houses to taverns.

The contemporary perception of Diyarbakır is almost absolute in its certainty that this is a “Kurdish city”. Yet Diyarbekir, despite being at the centre of a broad Kurdish landscape, is the centre of a deep cosmopolitism that has accumulated since ancient times –like many other cities of Asia Minor and Mesopotamia. The city of Amida (Diyarbekir) is known since the age of the Assyrian Empire, and just like Aleppo, Nineveh (contemporary Mosul) and Babylon (close to contemporary Baghdad), was one of the political, economic and cultural centres of Upper Mesopotamia. Located at a highly strategic point where roads leading from Caucasia to the Eastern Mediterranean, from Iran to Anatolia and from the shores of the Black Sea to the Persian Gulf intersect, the city appeared as a Northern Assyrian capital in the late 2nd millennium BC, becoming a centre of attraction for merchants, and the peoples of surrounding lands from Asia Minor to Mesopotamia, and even Persia.

The wealth and diversity the city began to accumulate from the Bronze Age on served as the basis of a unique culture. The clearest sign of this wealth and the increasing importance of the city is the Diyarbekir city walls, believed to be built in the 4th century, and recognized as the “second longest city wall structure in the world”. The Roman and Eastern Roman Empires that sought to conquer the world from west to east, and thus, Mesopotamia and Persia, and the Persian and Sassanid Empires that tried the same in the opposite direction, targeting Asia Minor, the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean worlds, transformed the city into their headquarters. The city was the capital of the Mesopotamia Province of the Roman Empire. Neither of the two powers achieved their objective, yet they continued to consolidate and develop this great city on the Tigris River, that would remain, for a long time to come, the borderline between the worlds of the East and West. As the city frequently changed hands between the two great powers, Amida’s pagan population grew with the arrival of peoples under the rule of the Roman and Sassanid Empires. In this sense, the fate of Nusaybin, and later Dara closely resembled that of Amida. These two cities collapsed under intense clashes, yet Amida continued to stand.

Once the Roman Empire accepted Christianity as its official religion, the ancient peoples living in the region also adopted Christianity and emerged with their contemporary identity. The Armenian and Syriac peoples of Upper Mesopotamia, and even some Arab groups, severed their ties with their Pagan past and swiftly organized around the church. The still-standing city of Diyarbekir became one of the regional centres of this development. Once the churches of these two nations dissociated themselves from the imperial church, their identities stood out stronger, and became more competitive. On the other hand, the Roman-Sassanid peace in the late 4th century led to many Christians living in Sassanid Iraq and Iran migrating to Diyarbekir. Among them were, in addition to a majority of Assyrians, Armenians, Christian Arabs, Christian Persians and even Christian Kurds. It was for this new influx that the church known as Mor Toma, the remains of which today lie in the foundations of the Ulu Cami mosque, was built as probably the largest church in the region. From as early as the 4th century on, Christians from different ethnic groups dissolved within the Armenian and Syriac communities which had the largest and best-organized churches in the region –until when, from within the Ancient Syriac community, the Nestorian and Chaldean communities appeared.

When, in the 7th century, Muslim Arabs conquered the city and swept elements of the Eastern Roman Empire away from the empire, a balance emerged between these communities that begun to live under Arab rule, and the constantly increasing Muslim Arab population. Arabs also attracted other Muslim peoples to the city. First the Bekr Arabs, that lent the city their name, and then the Şeybanî, Hamdanî and Büveyhî Arabs, administered the region extending to Caucasia and beyond the Taurus mountains from here, even if they did become vassals of the Abbasids from time to time. The Kurdish influence in the city increased during the Marwanid era. Under Arab rule, the Islamization of the Kurds also accelerated, and especially during the Marwanid era, the city became a centre where significant scholars of the four schools of Islamic theology gathered, and converted Kurds in the region to Islam.

In the 11th century, Turkoman raids that turned towards Asia Minor also had an impact on Diyarbekir. However, Diyarbekir did not immediately come under Turkoman control. From the 13th century on, we observe full Turkoman dominance and witness the emergence of ruling Turkish families and Turkoman presence around them. However, when in the same century Saladin conquered the city, Kurdish lords took power in the city, albeit for a brief period. This was followed by Artuqid, Aq Qoyunlu and Safavid reigns, exposing the city to broader Turkoman influence. A number of Turkoman nobles lived in the city and left their imprint.

The Mongols in the 13th century, and Timurids in the 15th century exerted absolute control over the region, yet they did not participate in the administration of the city, or join its notables. The Artuqids during the Mongol reign, and the Aq Qoyunlu during the Timurid reign continued to administer the city. When many households were forced to migrate from their villages to the city due to famine, drought and pillaging, the Kurdish and Armenian population of the city increased.

When the Ottoman era began, the city was still home to ancient Turkoman notables, and families that had settled during the Ayyubid and Arab rules. The working class population of the city was predominantly Kurdish and Armenian. Among the Kurds, there were a small number of Yezidi families. It was easier to convert the Yezidis to Sunni Islam. There were also smaller Syriac and Arab communities in the city, and also even lesser Nestorian, Jewish and Greek Orthodox groups. 16th century registers reveal that there was also a Şemsî community in the city, however, traces of the Şemsî population swiftly disappear.

Despite fluctuations, the ratio of Muslim and non-Muslim populations in Diyarbekir remained close for a long period. However, towards the end of the 16th century, the Christian population of the city doubled, and reached a majority. This was due to the migration of the Christian population in towns and villages to the east. The Christian population had organized itself under 26 church congregations. The Armenian Orthodox and Ancient Syriac communities dominated, with also Greek Orthodox and Nestorian communities. The Jewish community of the city, unconventionally, was for a period registered under the Nestorian church. After the Ottoman conquest of the city, the Albanian and Caucasian administrators and the janissaries they sent became the notable families of the city. These families, like a certain section of urban Arabs, underwent Turkification or Kurdification over time.

Nomadic Kurdish tribes did not live either in the city or in villages, yet Diyarbekir was their most important market place. This was where they often presented their animal products to the market, and procured their own needs.

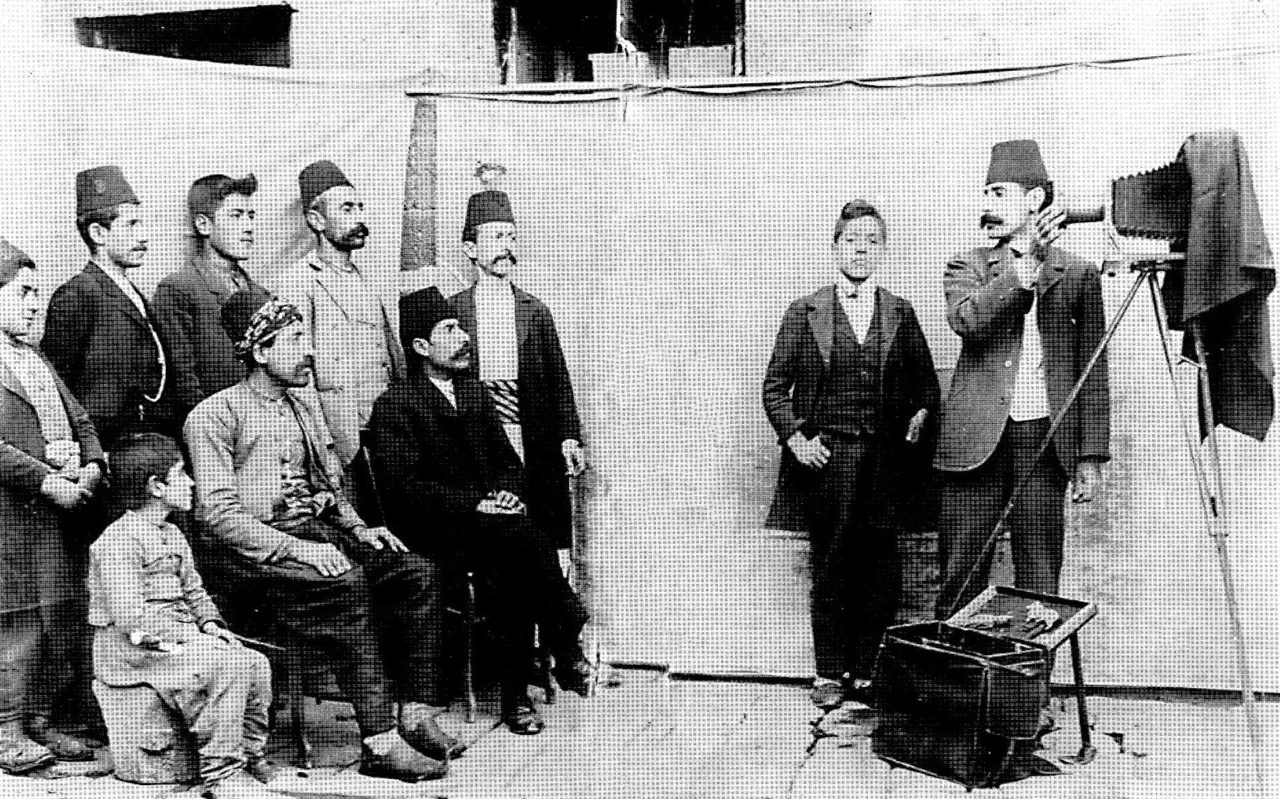

In the 19th century the Ottoman Empire began its process of Westernization in order to integrate with the West, and the centre of this new development in the east was, once again, Diyarbekir. Along with the Tanzimat (Reorganization) reforms, one of the eastern bases of the central government to establish full dominance over all provinces was, alongside Erzincan and Elaziz, Diyarbekir. Diyarbekir was also the capital of Kurdistan Province, and became the centre of the new and broader eponymous province founded as part of reforms. This province comprised the entire Upper Tigris Basin as far as Siirt, and also Mardin and Siverek. This development also turned Diyarbekir into the intellectual and cultural centre of a wide area. As Diyarbekir became the first city to open up to the West in the region, the entire area entered under the influence of both goods and ideas arriving from the West. This meant that the city witnessed the rise of new forms of identity and belonging.

Meanwhile, in the second half of the 19th century, with the impact of missionary work, Armenian Protestant and Catholic and Syriac Protestant and Catholic communities became part of the cultural and religious diversity at a level that meant they assumed important roles in social life. The Muslim-non-Muslim demographic balance of Diyarbekir did not change in the late 19th century either, the city retained the almost equal balance that went back to the second half of the 16th century.

It had now also become easier for the intellectual spirit of Istanbul and Europe to swiftly spread to Diyarbekir and influence the local intelligentsia that included prominent figures from all communities. In the 19th century, especially because of Milli İbrahim Paşa’s raids on the environs of Diyarbekir, the city received intensive migration inflow from Zaza villages in the area, and the percentage of Zazas among the Kurdish population began to increase. Missionaries, merchants and consuls had also become part of this diversity, and small European communities had long formed in the city. Benefiting from the influence of Capuchins, French merchants formed the majority among merchants. There were also Persians and Arabs among the community of merchants.

In brief, Diyarbekir, as early as the 19th century, had assumed its cosmopolitan character that rose on an accumulation of urbanity dating back to antiquity. In this sense, it resembled Aleppo, Ankara in the 18th century, or late 19th century İzmir.

Today, Diyarbakır is a city with a Kurdish majority. However, historically, the city always displayed a diversity dominated by no ethnic group or community, and thus incorporated a pluralism parallel to that.

A cosmopolitan metropolis must be “a city of peace”. That is how it retains its standing. Therefore, throughout history, the real threat to peace in Diyarbekir did not come from interest groups or communities that could cause internal conflict, but from the outside. As for disquiet in the city, it was not caused by conflicts between different communities, but between the holders of power, from whichever community or ethnic background they may be, and the city’s working class.

This kind of city attracts people from all walks of life, those seeking wealth, a living, protection or to comfortably live their life the way they want to. Diyarbekir was open to all the peoples of the historical-cultural lands it stood in the centre of, that landscape nurtured Diyarbakır and this cosmopolitism also educated its environment to a certain extent. This resulted in a unique urban culture, a cultural character that could be described as “belonging to, or being from Diyarbekir”. Although nothing would remain of it in the coming period, what Mıgırdiç Margosyan narrates in “Gâvur Mahallesi/Giaour Neighbourhood” is a picture of the final period of this urban and cosmopolitan condition.

It is possible to say that the diversity of the city was destroyed with the deportation of Armenians, implemented with tremendous violence in 1915. After that date, the Armenian population of the city, whether Orthodox, Catholic or Protestant, was reduced to hundreds, and faded away over time. Parallel to this, the Syriac and Chaldean population of the city also diminished, leaving behind small communities. The Nestorian population especially, moved gradually to Iraq and Iran from the first half of the 19th century on.

The Diyarbekir Jews, also known as “Kurdish Jews”, along with the Çermik Jews, left the city following the foundation of the State of Israel in 1948. This meant that this cosmopolitan metropolis turned into an administrative centre in the early Republican period, where the apparatuses of modernization and nation-building were gathered together. Diyarbakır became a local centre which also provided services for the smaller cities and towns in its vicinity alongside its own villages, fulfilling functions unique to 3rd or 4th-level centres. As for traces of the religious and ethnic diversity representing Diyarbekir’s past, they unfortunately faced serious damage from the early Republican period on, and to a great extent, such traces were completely destroyed.

Almost “purified” of non-Muslims today, the story of Diyarbekir in the Republican period is officially told under the city’s new name, “Diyarbakır”.

According to the 1927 census, in the province, villages included, the number of Armenians was 2,490, that of Catholics and Protestants 402 and that of Jews, 392. The small number of Syriacs was probably included with Armenians. In contrast, the Muslim population stood at 185 thousand. Yet the Diyarbekir Annual of 1870 counted around 9,800 Muslims, 7,500 Armenians including both Orthodox and Catholic denominations, around 1,000Syriacs, including Catholics, 1,500, Chaldeans, 360 Greeks, both Orthodox and Catholic, 650 Protestants and 280 Jews. The total population of non-Muslims was more than the population of Muslims. (Around 11 thousand non-Muslims and 9,800 Muslims)

In the 1927 population census, 132 thousand people stated their mother tongue as Kurdish, while there were 56 thousand Turkish speakers, 2,200 Arabic and around 1,000 Armenian speakers across the province. Kurdish speakers constituted 68% of the population of the province.

Compared with late 19th century percentages, the ratio of Armenians and Syriacs in the city’s population has diminished from around 43% to 3% in this period of time. Interestingly, the majority of those who declare Turkish as their mother tongue live in Zaza areas (Ergani, Çermik and Çüngüş). At the 1965 census (the last census when mother tongue was included among questions asked) the number of people across Diyarbakır stating that their mother tongue is either Kurmanji or Zazaki/Kirmanjki reached 294 thousand (around 62% of the total population). 178 thousand responded that their mother tongue was 178 thousand, while around 2,500 answered Arabic. There are no records stating how many residents spoke Armenian or Syriac as their mother tongue. However, we can estimate that they numbered in the hundreds. There were almost no Armenians living in the city, and the ancient Syriac community only filled a single church.

Taking into consideration the reserve in the face of the nation-state of those providing information to a census carried out by the state, one could argue that the number of those who declared Turkish as their mother tongue is exaggerated. Besides, the fact that the city of Diyarbakır is an administrative and economic centre means that those who speak Turkish as a mother tongue are represented in higher figures.

Today, Muslims speaking Turkish and Kurdish constitute an overwhelming majority of the city’s population. Although there is no statistical data on the subject, it is possible and reasonable to say that Kurmanc and Zaza form the majority within that group. Enforced village evacuations that began in the 1990s further increased the Kurdish population of Diyarbakır. In 1965, Diyarbakır’s urban population was around 100 thousand, this reached only around three times that by the 1990s. However, in the year 2000, the figure was 545 thousand, and in 2010, 900 thousand. At present, the city has a population over a million. This speed of population increase indicates a threshold unlike any other metropolis in Turkey. This tendency began with the intensification of enforced village evacuations, and increased with further migration from the countryside to metropolises in the 1990s, and represents the high mobility from provinces in the near vicinity of Diyarbakır, therefore involving Kurmanc and Zaza populations.

Text: Prof. Dr. Suavi Aydın, Anthropologist

Translation: Nazım Dikbaş

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

• Beysanoğlu, Ş. (1962) Diyarbakır Coğrafyası [The Geography of Diyarbakır], Şehir Matbaası, Istanbul.

• Diken, Ş. (2013) “Diyarbakır ‘Hangi’ Mahle? [‘Which’ Neighbourhood is Diyarbakır?]”, Diyarbakır ve Çevresi Toplumsal ve Ekonomik Tarihi Konferansı Tebliğleri, Hrant Dink Vakfı, Istanbul: 421-426.

• Ertem, Ö. (2013) “‘Fiyatı Âlidir!’ Diyarbakır’da Kıtlık, Yokluk ve Şiddet, 1879-1901 [‘It’s Price Is High!’ Famine, Poverty and Violence in Diyarbakır, 1879-1901]”, Diyarbakır ve Çevresi Toplumsal ve Ekonomik Tarihi Konferansı Tebliğleri, Hrant Dink Vakfı, Istanbul: 73-79.

• Hovanissian, R. G. (ed.), (2006) Armenian Tigranakert/Diarbekir and Edessa/Urfa, Mazda Publishers, Costa Mesa, California.

• İlhan, M. M. (2000) Amid (Diyarbakır): 1518 Tarihli Defter-i Mufassal [Amid (Diyarbakır): The Survey Register Dated 1518], TTK Yayınları, Ankara.

• Jongerden, J. and Verheij J. (ed.), (2012) Social Relations in Ottoman Diyarbekir, 1870-1915, Brill, Leiden.

• Karalevsky, C. (1914) “Amid”, Dictionnaire d’histoire et de géographie ecclésiastiques, Vol. 2, Letouzey et Ané, Paris: 1237-1249.

• Kessel, G. (2015) “Manuscript Collection of the Syrian Orthodox Church Meryemana in Diyarbakır: A Preliminary Survey”, Manuscripta Syriaca. Des sources de première main, (ed.) Françoise Briquel Chatonnet and Muriel Debié, Geuthner, Paris: 79-123.

• Margosyan, M. (1994) Gâvur Mahallesi [Giaour Neighbourhood], Aras Yayınları, Istanbul.

• McDowall, D. (2007) A Modern History of the Kurds, I.B. Tauris, London and New York.

• Najarian, P. (2006) Son Ermeni [Voyages], translated into Turkish by İnci Batuk, Aras Yayınları, Istanbul.

• Restle, M. (1966) “Amida”, Reallexikon zur byzantinischen Kunst, Vol. 1, A. Hiersemann, Stuttgart: 133-137.

• Taşğın, A. (2008) “Şemsîler [The Şemsîs]”, Osmanlı’dan Cumhuriyet’e Diyarbakır [Diyarbakır from the Ottoman Empire to the Republic], Vol. 3, (ed.) Bahaeddin Yediyıldız and Kerstin Tomenendal, published by the Diyarbakır Governorate and Türk Kültürünü Araştırma Enstitüsü [Turkish Culture Research Institute], Ankara: 753-762.

• Tezokur, M. H. (2008) “XIX. Yüzyıl Diyarbakır’ında Süryaniler [Syriacs in XIX. Century Diyarbakır]”, Osmanlı’dan Cumhuriyet’e Diyarbakır [Diyarbakır from the Ottoman Empire to the Republic], Vol. 3, (ed.) Bahaeddin Yediyıldız and Kerstin Tomenendal, published by the Diyarbakır Governorate and Türk Kültürünü Araştırma Enstitüsü [Turkish Culture Research Institute], Ankara: 645-661.

• Teule, H. (2008) “Joseph II, Chaldean Patriarch in Diyarbakır and the Intellectual Orientations of his Community at the End of the 17th Century and the Beginning of the 18th Century”, Osmanlı’dan Cumhuriyet’e Diyarbakır [Diyarbakır from the Ottoman Empire to the Republic], Vol. 3, (ed.) Bahaeddin Yediyıldız and Kerstin Tomenendal, published by the Diyarbakır Governorate and Türk Kültürünü Araştırma Enstitüsü [Turkish Culture Research Institute], Ankara: 677-686.

• Yılmazçelik, İ. (2014) XIX. Yüzyılın İlk Yarısında Diyarbakır (1790-1840) [Diyarbakır in the First Half of the XIX. Century (1790-1840)], TTK Yayınları, Ankara.

EXHIBITION CREDITS

Contributing authors

Assoc. Prof. Birgül Açıkyıldız, Prof. Dr. Suavi Aydın, Assoc. Prof. Emine Ekinci Dağtekin, Ara Dinkjian, Birsen İnal, Mehmet Mercan, Kenan Özhal, Silva Özyerli, Filiz Parlak, Dr. Clémence Scalbert Yücel, Can Şakarer, Mehmet Şimşek, Hayri Yoldaş

Exhibition editor

Pınar Öğünç

Translation

Murat Bayram, İnan Eroğlu (Kurdish)

Nazım Dikbaş, Onur Günay (English)

Design

Fika

Publication date

July 2020 / November 2020