TEACHING, DOCUMENTING

Here we present a series of names who recorded and documented the history of Diyarbakır in different ways, who worked in and contributed to the development of a diverse range of fields from astronomy to philosophy, medicine to architecture.

Writer Mehmet Şimşek prepared this collection of portraits of people whose paths crossed through Diyarbakır in the city’s history of many centuries. By coming together in this particular constellation, these names also provide a glimpse into the multicultural and multi-faith past of the city.

Mar Marutha

Although the exact year is unknown, Mar (Saint) Marutha was born in Mayyafariqin (Silvan). He was a famous scholar and physician fluent in Syriac, Greek and Persian. In addition to this, he was also responsible for the diplomatic mission to the Persian Court in the name of the Byzantine Empire. He was sent as envoy to Persian King Yazdegerd I by Byzantine emperors Arcadius and Theodosius II three times in 399, 403 and 408.

Mar Marutha undertook a translation of the Nicene Creed¹ for the Assyrian Church of the East. In 410, he helped gather the Council of Seleucia (Ctesiphon), recognized as the first Assyrian Council to take place in Sassanid lands. Presiding over the Council with Mar Isaac, he made great contributions to the internal organization and centralization of the Assyrian Church of the East.

He penned the life stories of eastern saints persecuted by Persian King Shapur II (309-379). Behind the renaming of Silvan as Martyropolis (City of Martyrs), lies the story of how Marutha brought here the bones of saints, who were denied a burial, and interred them in a martyr’s cemetery.

Passing away in 421, Saint Marutha contributed many works in the Syriac language. Those known today are: On the Council of Nicaea, Orations and Disquitions, On the Mystery of the Church, On the Mystery of the Third Day of the Week, On the Martyrdom of Saint Simeon and other Martyrs, On the Holiness of Christ.

¹ A text consisting of 20 articles adopted by the Council of Nicaea that was convened in 325.

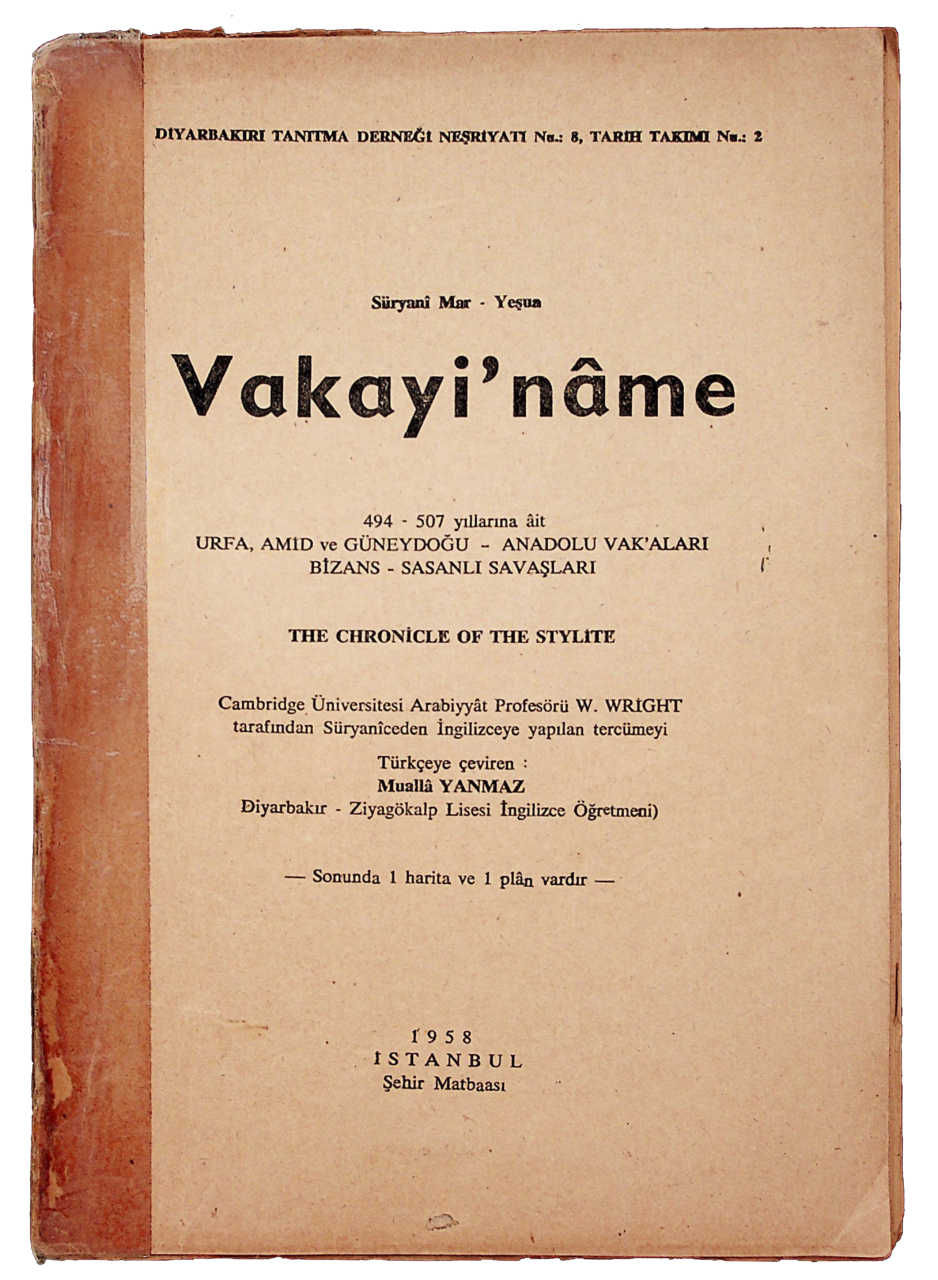

Mar Joshua

Featured in Syriac sources as Yeshu Stylite (‘Joshua the Stylite’), Mar Joshua lived at the end of the 5th and start of the 6th century. He taught at educational facilities of his time and at the Monastery of Zuqnin. The fact that he refers to Jacob of Serugh and Philoxenus of Mabbog in his chronicle indicates that he adhered to the Monophysite¹ doctrine. He begins his work by stating that he wrote it at the request of Sergius, abbot of a monastery near Edessa (Urfa).

The Chronicle of Mar Joshua is a prime example of the tradition of historiography that holds an important place in Assyrian history. Another aspect that makes Syriac chronicles ever more invaluable today is the fact that they are not written from the perspective of the rulers of the time unlike many of their contemporaries.

The chronicle, which was later turned into a book titled A History of the Time of Affliction at Edessa and Amida and Throughout All Mesopotamia remains an exceptional document on the political, military, religious, economic and social history of its period. This testimony focusing particularly on the reigns of Byzantine Emperor Anastasius and Persian Shahanshah (King of Kings) Kavadh (also spelled Qobad), namely the years 494 to 506, first and foremost serves to record the experience and repercussions of the Byzantine-Sasanian wars in the regions of Amida and Edessa. Mar Joshua provides a first-hand account of the true dimensions of scarcity and famine along with wars, sieges and uprisings. Headings such as earthquakes, pestilences, the plague of boils, locust outbreaks reveal the extent of how the region truly suffered a time of affliction in these 12 years.

¹ A term used to explain the nature of Christ, holding that although Christ has both a human and divine nature, his divine nature has absorbed the human, resulting in only one nature – the divine.

John of Agel

Born in Agel (Eğil) in the province of Amida (Diyarbakır) in 507, John (Yuhanna) of Agel is one of the important figures in ecclesiastical history and the history of the Byzantine Church.

He entered the Monastery of Mar Maron and was educated here for a while before moving on to the Monastery of Mar John (Urtoyo). He spent his years from 530 to 541 traveling the world “like a minstrel” in order to expand his knowledge and horizons. Following visits to Antioch, Egypt, and Istanbul he turned to Mesopotamia.

He was received by Byzantine Emperor Justinian in 542 and was tasked by the emperor with a mission to spread the teachings of the Bible to the regions of Phrygia, Lydia and Caria in Asia Minor (Anatolia).

The reason John of Agel is commonly known as John of Ephesus is the fact that he was consecrated and served as Bishop of Ephesus for many long years. Sources say that he had 99 churches and 12 monasteries built in this period.

His wide-reaching sphere of influence and the high esteem in which he was held made him a target for certain circles. During the reign of Justin II, John was sent to live in exile on an island in the Aegean for 49 months, and he was then imprisoned by Emperor Tiberius. Through this period of exile and imprisonment he composed his three-part Ecclesiastical History and two-part Lives of the Eastern Saints. Although one has perished, two parts of his Ecclesiastical History are currently preserved in the British Library in London.

John of Agel –or Ephesus– was forced into hiding when he was banished from Istanbul as supporters of the Council of Chalcedon gained ground. He was imprisoned twice in this period and finally lost his life while in prison in the year 586, during the reign of Maurice.

Aëtius of Amida

Though his exact dates of birth and death are unknown, he is believed to have been born in what is now Diyarbakır and to have lived at the end of the 5th and start of the 6th centuries. After studying at Alexandria, the most famous medical school of the age, Aëtius returned to his hometown to work as a physician. In the meanwhile, his medical endeavors took him to Cyprus, Jericho and the Dead Sea. Before long, he won the notice of Eastern Roman Emperor Justinian the Great and traveled to Istanbul. Here he stayed in the Byzantine Court for a while and worked as court physician and military physician of high rank.

16 works belonging to Aëtius of Amida focusing on different branches of medicine have reached our day. This corpus provides ample description of the medical practices of antiquity, and heavily quotes from his predecessors Galen and Oribasius – both of whom are medical scholars from Pergamum. In terms of mental illnesses and their symptoms he discusses phrenitis, loss of consciousness, melancholia and mania. The contraceptive medicinal concoctions he created as well as his method for removing tattoos are first to come to mind in association with his name today. Variations of this method for tattoo removal were, in fact, in use until laser technology was developed in the 1990s.

Many of his books started being printed in German, Greek and Latin from the 19th century onwards. Aëtius is also known to have translated medical works from their Greek originals into Syriac.

The Priest of Zuqnin

While his actual name remains a mystery, the Priest of Zuqnin¹ has gone down in history by this appellation, as it is featured in Assyrian records. He lived in the Monastery of Zuqnin near the present-day village of Alçık, previously called Fidelan. Though his chronicle was initially ascribed to Dionysius of Tel-Mahre, this turned out to be false over time (hence the name “Pseudo-Dionysius”).

In the first of this four-part chronicle written around 775, the anonymous Priest of Zuqnin reaches the epoch of Constantine the Great. The second part features up to the reign of Theodosius II, while the third extends to Justin II. In the fourth part, the author has recorded the events of his own time. What he highlights from this time period coinciding with the end of the Umayyad Dynasty and start of the Abbasid, contains important information on local cultures, languages and the origins of various peoples. The Chronicle of Zuqnin (or Zuqnin Chronicle) is also of note for what it records of the history of Diyarbakır and its environs.

¹ t.n. Some scholars propose the name “Pseudo-Dionysius”.

Ahmad ibn Jamil al-Amidi

This very first known master of Anatolian Islamic architecture was born at an unknown date. What we do know is that he worked as architect-engineer during the reconstruction of the city walls of Diyarbakır commissioned by Abbasid caliph al-Muqtadir Bi-llah in the early 10th century. His name is mentioned in four epigraphs dated 909 inscribed on the Harput (or Mountain) Gate and Mardin Gate sections of the walls. It is through these inscriptions that we are also able to confirm that he is from Diyarbakır – or Amid as it was known back in his day.

Though records show that Ahmad ibn Jamil had a high command of engineering and a special construction technique, it is at present impossible to discern whether he followed the original plans and façade designs during the repair and rebuilding of destroyed portions of the city walls, and if he did make certain changes in which parts and to what extent these were.

“In the name of God, the merciful and the compassionate. This is what has been commissioned by the ruler of believers, Imam Abd Allah Ja’far al-Muqtadir Bi-llah –may God grant him long life and glory– in order to exalt our religion and protect Muslims. It has been executed by Vizier Ali son of Abu al-Hasan Muhammad –may God grant him long life–. Expenditures for this structure have been made in the custody of Yahya son of Ishaq of Jarjara and Ahmad son of Jamil of Amid in the year 297.”

(Photograph: Merthan Anık, 2009)

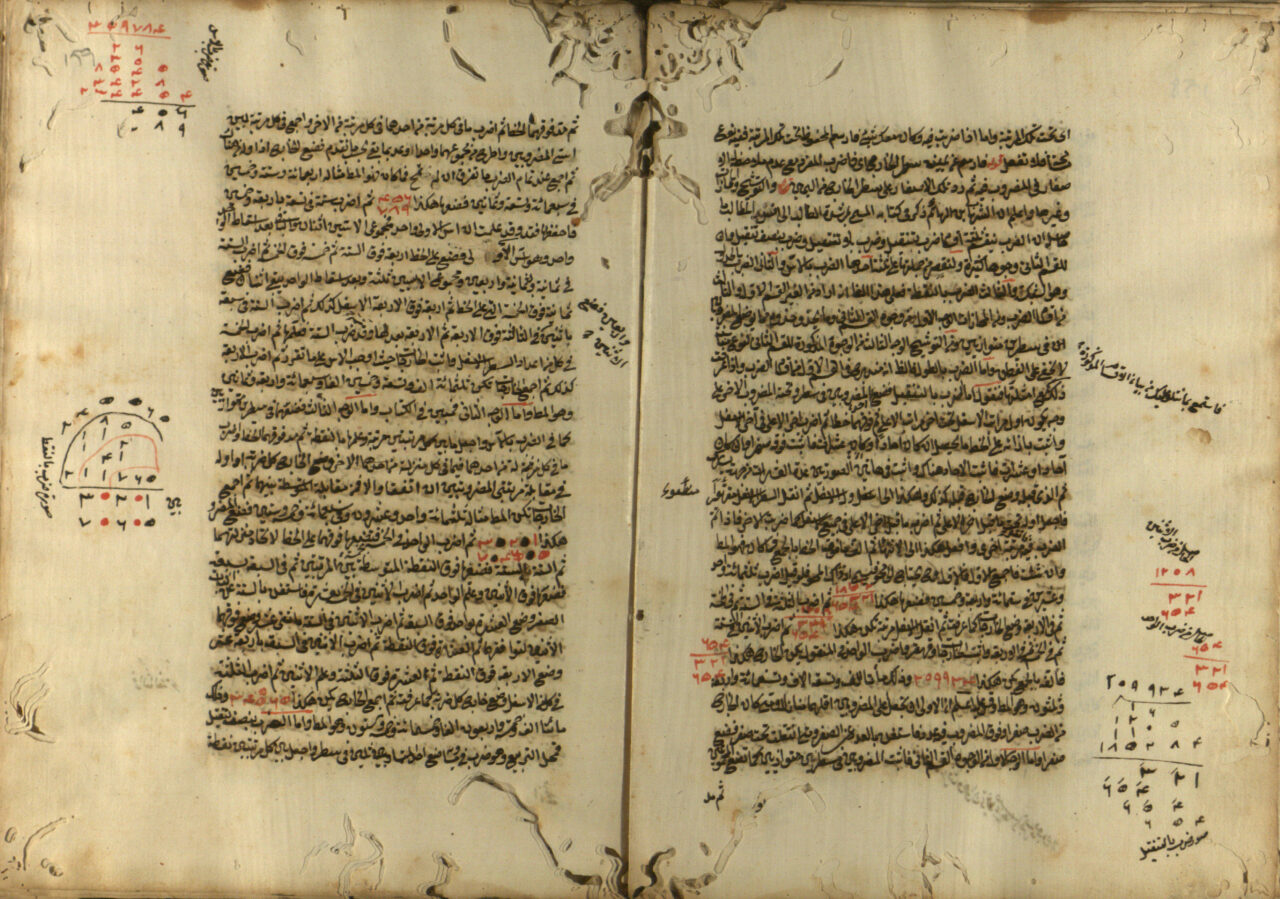

Ibn al-Azraq al-Fariqi

Chronicler and historian Ibn al-Azraq al-Fariqi was born in Mayyafariqin (Silvan), Diyarbakır (Amid) in February 1117. Although he does not provide much detail regarding his childhood in his memoir, we do know that his family were among the notables of their time. His grandfather Abu al-Hasan Reis Ali ibn Azraq took on various administrative posts in Hasankeyf and served as governor of Diyarbakır for a while.

Ibn al-Azraq received an education in the Quran, hadith, fiqh (jurisprudence), Islamic law, grammar and literature from prominent masters of the period, but it would be his interest in history that eventually made him one of the important historians of the Middle Ages. He recorded the events of the Artuqid era based on documents, his personal observations, and the accounts of first-hand witnesses. He served in various official capacities and undertook many journeys some of which were on account of his official duties. It is known that he spent time in cities such as Tabriz, Ray, Mosul, Harran, Aleppo, Hama, Homs, Manbij, Ras al-Ain, and Damascus (al-Sham). Having gained a thorough understanding of the Islamic lands, Ibn al-Azraq also lived in Georgia for a while, staying in the court of Georgian King Demetrius in Tbilisi.

His most comprehensive as well as currently best known and most acclaimed work is the Tarikh Mayyafariqin wa-Amid (Tarikh al-Fariqi). He wrote in the colloquial Arabic spoken in the region bearing influences of Turkish and Kurdish. His value as a historian stems from his attention to detail and his diverse range of sources. For instance, when writing on the establishment of Mayyafariqin and the etymological roots of its name he does not refrain from citing Syriac source texts. The sections of the Tarikh Mayyafariqin wa-Amid covering the Marwanid period remain to date one of the most important sources of Kurdish historiography.

Ibn al-Azraq al-Fariqi passed away in 1181.

Umar ibn Ahmad al-Chilli

The full name of this scholar of mathematics, astronomy and geography from Diyarbakır is Umar ibn Ahmad al-Ma’i al-Chilli. Though unclear, his birth is dated to the latter half of the 16th century, while there is more information on the date of his death – records mention that he died in the year 1613. We know little about his life, except for the fact that he took on the name “al-Chilli” after the village of Chilli (Tavşantepe) in Diyarbakır where he was born and the Madrasa of al-Ma’i al-Chilli where he was educated and most probably later taught.

Umar ibn Ahmad al-Chilli is known for his annotations and commentary on the Khulasat al-Hisab (Compendium of Arithmetic) of Baha’ al-Din al-Amili (died 1622) and on Yahya ibn Muhammad ibn Muhammad al-Hattab’s works on astronomy. In addition to these, his contributions to Ottoman scientific literature in the fields of mathematics, geometry and astronomy are hailed in many sources.

Along with his written works, Umar ibn Ahmad al-Chilli raised many students as well, the most famous of whom is Diwan poet Mullah Chalabi al-Amidi also from Diyarbakır. Copies of his works are available in the Âtıf Efendi Library, Cebeci Library, Manisa Library, Archaeological Museum Library, National Library, İzmir National Library, Nuruosmaniye Library, Kandilli Observatory Library, Çorlulu Ali Pasha Library, and the Libraries of the American University of Beirut.

Tovmas Zavzavatdjian

The process of reforms started by the central government towards the mid-19th century created a vibrant educational environment for the Armenian community of Diyarbakır. Born in Diyarbakır in 1842, Tovmas Zavzavatdjian is one of the most prominent educators of his time.

Zavzavatdjian studied at the Theological Seminary of Jerusalem in 1860. In 1865, he founded the Hayrenaser (Patriotic) Society in Diyarbakır with other devotees of education like himself. In that same year, this organization opened the Hayrenasirats school, which was a coeducational school where girls and boys studied together.

Another initiative by Zavzavatdjian was a series of lectures and discussions for adults, held on Sundays. Their purpose was to encourage the poor in particular to learn a trade and skills that would lift them out of a life reliant on begging or alms handed out by the church. This attracted the displeasure of certain religious authorities and wealthy merchant circles. To hold his ground in this clash, Zavzavtdjian took the route he knew best and staged two plays titled Ignorance and Progress, and Norayr with pupils of the Hayrenasirats School. These were satires on the attempts of the religious leaders of his community to suppress and intimidate himself and his school. This would not go without consequence. Eventually, as a result of complaints by Armenian Archbishop, the Hayrenasirats School was shut down in April 1872. Tovmas Zavzavatdjian had to take an extended leave from teaching and passed away in 1911.

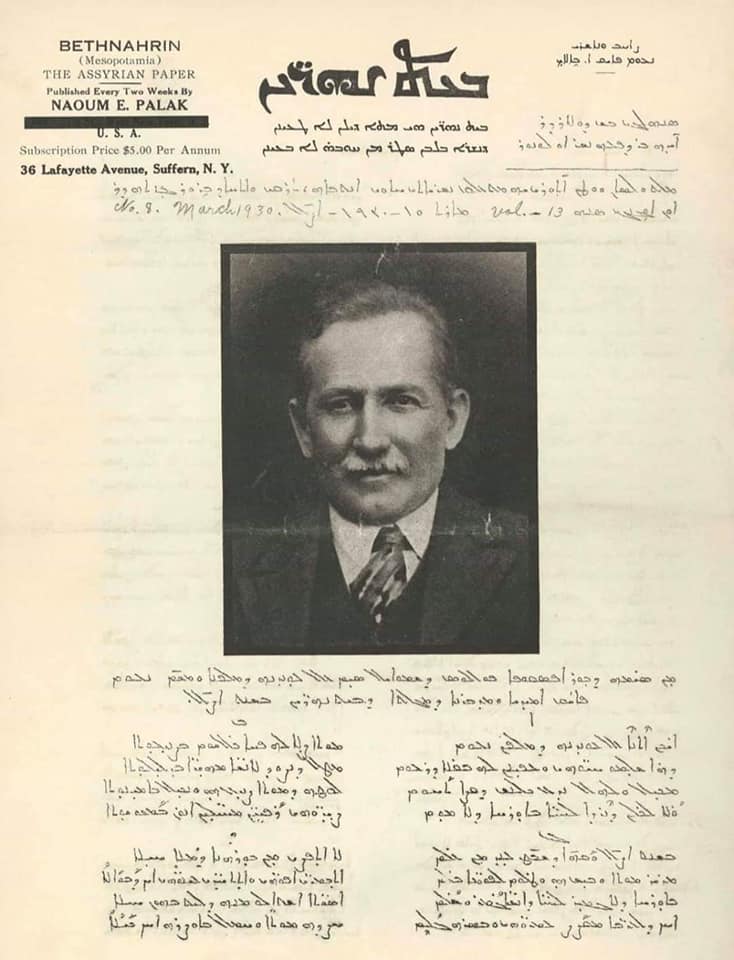

Naum Faiq Palakh

Intellectual and writer Naum Faiq Palakh, known particularly for his work in the field of language and as a pioneer of the “Assyrian Awakening” or Renaissance, was born in Diyarbakır in 1868. He was fluent in Syriac, Turkish, Kurdish, Persian and English. For 20 years he taught at an Assyrian school at junior high (rüşdiye) level in the Virgin Mary Church in Diyarbakır. He also taught for briefer periods in Assyrian schools in Adıyaman, Urfa and the Hashas village in the Beshiri region.

The Second Constitutional Period inaugurated on July 23, 1908, sparked a publishing boom all over the Empire. In this period, Kawkab Madnho (“Star of the East”), a newspaper that was the very first publication of its kind in the Syriac language came into being upon the initiative of Naum Faiq Palakh. Published primarily in Turkish, Syriac and Arabic written entirely in the Syriac alphabet, it ran for 43 issues between 1910 and 1912.

When the outbreak of the Italo-Turkish War (Tripolitanian War) sparked backlash against non-Muslims, Naum Faiq Palakh left to move to the U.S. with his family in 1912. He kept publishing here as well and eventually passed away in 1930.

He has about 40 books to his name mostly in philology. Some are: Syriac Words in Turkish, Syriac Words in Armenian and Kurdish, Principles of Reading in the Syriac Language, History of Assyrians Migrating to the U.S., History of the Madrasas of Urfa and Nisibis, Slang of the Arabic-Speaking Folk of Diyarbakır, and Anthems in Syriac, Arabic and Turkish.

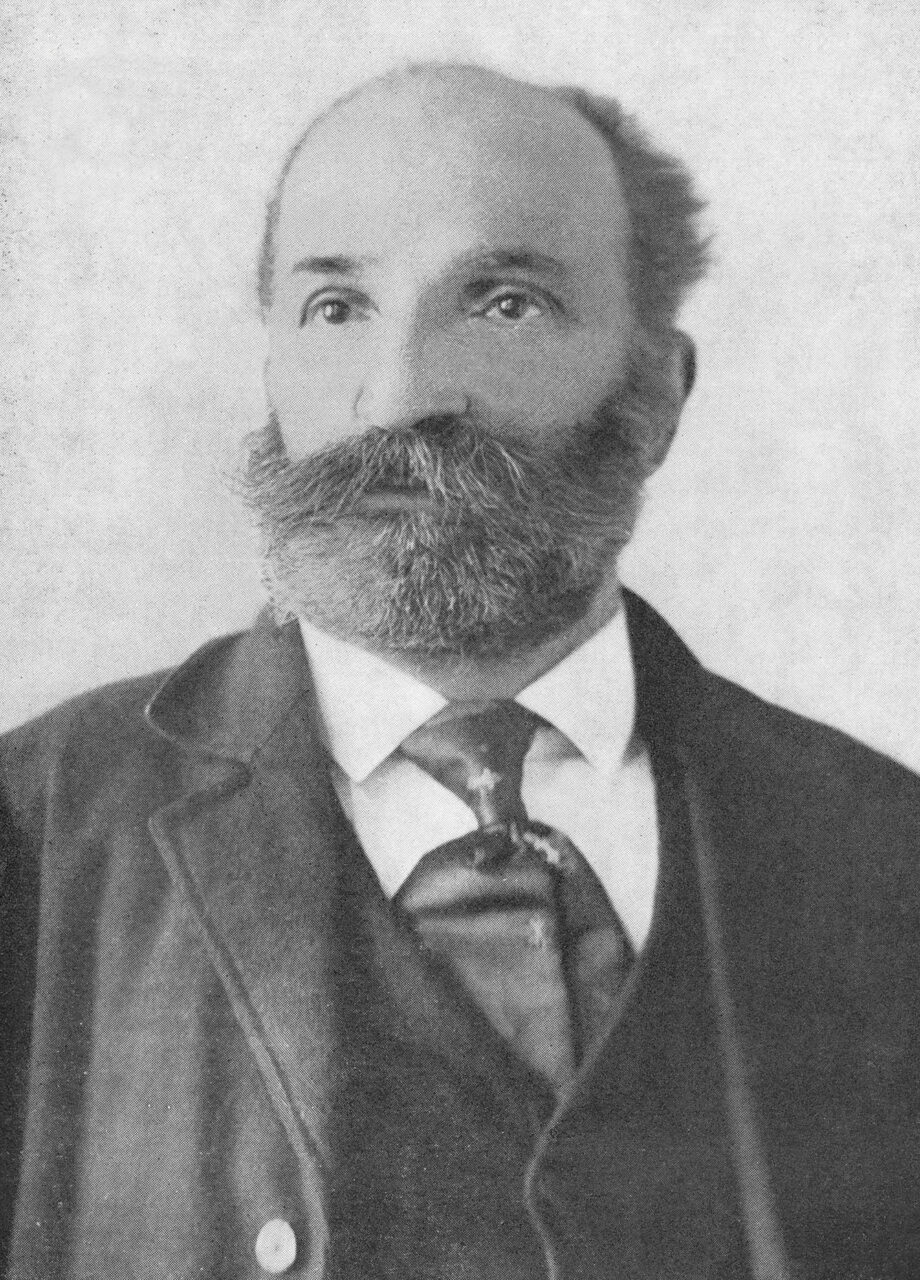

Şeyh Abdurrahman Aktepe

Sheikh Abdurrahman Aktepe was born in 1854, in the village of Aktepe, under the Çınar district of Diyarbakır. He received his early education from his father, Sheikh Hasan al-Nurani of the Naqshbendi-Khalidi order, moving on to the madrasas of Damascus to improve his knowledge of Arabic, sarf and nahw (grammar and syntax). After completing his education, he in turn worked as mudarris (teacher, professor) at the madrasa in the village of Aktepe.

Writing masterful poems that elegantly combine didacticism and lyricism under the pseudonyms “Ruhi” and “Shams al-Din”, Sheikh Abdurrahman Aktepe developed a special interest in the sciences of philosophy, logic, astronomy and chemistry.

He tracked the movements of the moon, sun, stars and planets from Diyarbakır and its environs and sought to make a model of the solar system using nut shells. He has a treatise specializing on astronomy titled Kifayat al-Awqat, a two-volume work on logic and philosophy consisting of 90 pages each titled Kitab al-Mantiq, and Kitab al-Tıb which offers succinct information on the remedy of various illnesses and certain medicines.

Sheikh Abdurrahman Aktepe passed away in 1910.

Viktorya Hanım

Viktorya Hanım,¹ as many have come to know her, is the daughter of the sister to Mor Ignatius Elias III (Elias Shakir), who served as Patriarch of the Syriac Orthodox Church from 1917 to 1932. Her uncle, while Bishop of Amid (Diyarbakır) prior to becoming Patriarch, took an interest in the education of the Assyrian community. He paid particular attention to making better educational opportunities available to girls. In the meanwhile, Viktorya Hanım, having finished at the American Protestant Girls’ School of Mardin, came to teach at the Assyrian Girls’ School founded in Diyarbakır upon her uncle’s request.

With a good command of English and Arabic in addition to Syriac, Viktorya Hanım started teaching in the school adjacent to the Virgin Mary Church attended by 60 students. In addition to Syriac language, she instructed in a variety of subjects including Turkish and English, mathematics, proper writing skills, religion, handicrafts and alimentation. She was an educator whose influence was palpable in the Assyrian community of Diyarbakır at the time.

¹ t.n. ‘Hanım’ is a respectful term of address added after women’s names in Turkish, meaning ‘lady’, ‘madam’ – the male equivalent of which is ‘bey’.

Şevket Beysanoğlu

Known as the “man who introduced Diyarbakır to the country” due to his extensive work on the city and its culture spanning many years, Şevket Beysanoğlu was born in Diyarbakır in 1920. His father was Beysanzadeh Mullah Ahmed, a scholar from Diyarbakır. After receiving his primary and secondary education in Diyarbakır, he entered the Faculty of Law at Ankara University. He graduated in 1942 to work as a self-employed lawyer. His studies on Diyarbakır, which he began in 1956, evolved into a life-long enterprise.

He was one of the representatives in the Republican era of the biography tradition dating back to the 16th century Ottoman Empire, pioneered by names such as Ali Amiri and Ibn al-Amin Mahmud Kemal İnal. With his singular focus on life stories from a particular geographical area such as Diyarbakır, it is possible to place Beysanoğlu mostly within the Ali Amiri camp of historiography.

In his four-volume compilation titled Diyarbakırlı Fikir ve Sanat Adamları (Intellectuals and Artists of Diyarbakır) he covered biographies from the 4th century to the 20th. One of our main sources in the preparation of this exhibition as well, this tome contains 421 biographies, recording the life stories of 174 scientists, 228 poets and writers, five calligraphers, eight composers, and six painters. The total number of works featured in this compendium is listed as 3682.

26 of Beysanoğlu’s works are in the research-study category. He has collected 7 and edited 11 books. Some of his other works are: Anıtları ve Kitabeleriyle Diyarbakır Tarihi (A History of Diyarbakır with its Monuments and Inscriptions) (3 volumes), Diyarbakır Folkloru (The Folklore of Diyarbakır) (3 volumes), and Ziya Gökalp için Söylenenler (Ziya Gökalp in the Words of Others) (4 volumes).

Having started his literary career with poetry, one of Beysanoğlu’s first poems was also on Diyarbakır:

Born in your bosom

And in your bosom I will lie

As long as there is life in this body

It is you I will describe

Beysanoğlu is the founder of the Association for Tourism and the Promotion of Diyarbakır (Diyarbakır’ı Tanıtma ve Turizm Derneği), which later became the Foundation for Culture, Cooperation and the Promotion of Diyarbakır (Diyarbakır Tanıtma Kültür ve Yardımlaşma Vakfı). He also joined the membership of the Authors’ Association of Turkey (Türkiye Yazarlar Birliği). In 1990, he was awarded an honorary PhD in literature by Dicle University on account of his extensive studies on the history, geography and folklore of Diyarbakır. He donated most of his personal collection of near ten thousand volumes to the library of Dicle University, and passed away in Ankara on April 23, 2003.

Text: Mehmet Şimşek

Translation: Feride Eralp

Translator’s note: The Turkish term “Süryani” is an ethnic and religious designation that is variously translated as “Syriac”, “Assyrian”, and “Aramean/Aramaic”. There is much debate as to how this term should be used in English generating from sectarian or Christological differences, historical origin and etymological interpretation. The widespread understanding is that Syriac describes a language and Assyrian an ethnic/national identity. Preferring “Assyrian” would indeed suggest an ethnic identification describing people descending from the Assyrian Empire. But it is contested whether the ethnic identity encompasses everyone speaking the language, and whether the term “Assyrian” is a more modern usage (to disambiguate from “Syrian”) rather than what was used in Antiquity by these people to define themselves. For this reason, I will use Assyrian and Syriac interchangeably in translation of “Süryani”.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

• Barsavm, E. (2005) Saçılmış İnciler: Süryanilerin Yazınsal Tarihi [The scattered pearls: A history of Syriac literature and sciences], (trans.) Zeki Demir, Istanbul Süryani Ortodoks Metropolitliği, Istanbul.

• van Berchem, M., Strzygowski, J. and Bell, G. (2015) Amida, (ed.) Şeyhmus Diken, DİTAV Yayınları, Ankara.

• Beysanoğlu, Ş. (1960) Diyarbakırlı Fikir ve Sanat Adamları [Intellectuals and Artists of Diyarbakır], Vol 2, Diyarbakır’ı Tanıtma Derneği, Istanbul.

• Beysanoğlu, Ş. (1978) Diyarbakırlı Fikir ve Sanat Adamları [Intellectuals and Artists of Diyarbakır], Vol 3, Diyarbakır’ı Tanıtma ve Turizm Derneği, Ankara.

• Beysanoğlu, Ş. (1996) Anıtları ve Kitabeleriyle Diyarbakır Tarihi [A History of Diyarbakır with its Monuments and Inscriptions], Vol 1, Ankara.

• Beysanoğlu, Ş. (1996) Diyarbakırlı Fikir ve Sanat Adamları [Intellectuals and Artists of Diyarbakır], Vol 1, Diyarbakır Tanıtma, Kültür ve Yardımlaşma Vakfı, Ankara.

Çıkkı, M. F. (2019) Naum Faik ve Süryani Rönesansı [Naum Faiq and the Assyrian Awakening], Kent Işıkları Yayınları, Istanbul.

• Diken, Ş. (2019) “Tıp Bayramı ve Amidli Aetius” [“Medical Workers’ Day and Aetius of Amida”], Bianet.

• Duygu, Z. (2013) “Zuknin Manastırı Süryani Kroniği (775) Özelinde İslam İdâresi Altındaki Hıristiyanlarda ‘Din Değiştirme’ Meselesi” [The Issue of ‘Conversion’ among Christians under Muslim Rule as Featured in the Syriac Chronicle of the Zuqnin (775)”], Milel ve Nihal, 10(2): 173-201, Istanbul.

• Günel, A. (1970) Türk Süryaniler Tarihi [History of Turkish Assyrians], Oya Matbaası, Diyarbakır.

• Işık, İ. (2013) Diyarbakır Ansiklopedisi [Diyarbakır Encyclopedia], Vol I-II, Elvan Yayınları, Ankara.

• Kevkeb Medınho [Kawkab Madnho], 27 Jan 1912, 11: 6-7.

• Konyar, B. (1936) Diyarbekir Kitabeleri [Diyarbakır Epigraphs], Vol 2, Ulus Basımevi, Ankara.

• Mar Yeşua [Joshua] (1996) Urfa ve Diyarbakır’ın Felaket Çağı [Time of Affliction at Edessa and Amida], Yeryüzü Yayınları, Istanbul.

• Süryani Mar Yeşua [Joshua] (1958) Vakayi’name [Chronicle], (trans.) Mualla Yanmaz, Şehir Matbaası, Istanbul.

• Şimşek, M. (2012) “Doğu-Batı Süryani Kilise Tarihinde Silvan ve Mar Marutha” [“Silvan and Mar Marutha in the History of the Assyrian Churches of the East and West”], Uluslararası Silvan Sempozyumu [International Silvan Symposium] (25-27 April 2008), Istanbul.

• Şimşek, M. (2019) Süryaniler ve Diyarbakır [Assyrians and Diyarbakır], Kent Işıkları Yayınları, Istanbul.

• Tatoyan, R. (2020) “Diyarbekir – Schools”, (trans.) Simon Beugekian, Houshamadyan.

• TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi [TDV Encyclopedia of Islam], Vol 2, Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı Yayınları, Istanbul, 1989.

• TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi [TDV Encyclopedia of Islam], Vol 21, Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı Yayınları, Istanbul, 2000.

• TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi [TDV Encyclopedia of Islam], Vol 27, Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı Yayınları, Istanbul, 2003.

• Yousif, E. (2009) Süryani Vakanüvisler [Syriac Chroniclers], (trans.) Mustafa Aslan, Doz Yayınları, Istanbul.

INTO THE CITY