Here you will find the likes of Sırrî Hanım, one of the very few women to have become a Diwan poet, and Fatma Bacı, again a rare example of a woman saz poet (poet-singer), as well as Sami Hazinses, born Samuel Uluçyan, and İhsan Fikret Biçici, who made enormous contributions to Diyarbakır’s cultural life with the magazines he published and his poems…

Writer Ahmet Çakmak has prepared for us this selection of artists, writers and poets born in Diyarbakır, featuring snapshots of their works to complement their short life stories.

Sırrî Hanım

One of the few women poets in the Diwan tradition, Sırrî Hanım¹ was born in Diyarbakır in 1814. Her name at birth was Rahile. Her mother Fatma Hanım, a descendant of the Sheikhzadeh family, and her father Ahmed Bey paid the utmost attention to the education of Rahile and their other daughter Khadija İffet, who also became a poet. After learning Arabic and Farsi, Sırrî Hanım delved deep into Arabic and Persian literature.

Sırrî Hanım married Taher Aghazadeh Bekir Bey, with whom she had two sons named Muhammed Amin and Rifat, and a daughter named Nihal. The untimely death of a child – Nihal according to some sources, and Rifat according to others – took a heavy toll on the poet, and this tragedy led her to write the famous marsiya (elegy) by which she is known.

My back turned on this mortal world, my beloved I forswear

Unknowing of compassion, too callous at heart to bear

Fate denies me my heart’s desire, my world in despair

Torn from my precious darling, I live a nightmare

My soul a pool of blood like a crimson rosebud

Unwilling to blossom, though a thousand springs may come

For a while after 1873, Sırrî Hanım resided in Yusuf Kamil Pasha’s mansion in Istanbul, himself an important representative of Tanzimat era literature who was responsible for the first translation of a novel (Telemachus, François Fénelon) into Turkish. In this period, she became more established under Yusuf Kamil Pasha’s patronage. Although it is known that she had diwans (collections of poetry) in Farsi and Turkish, these works are lost to us. All that remains is a “diwanche” or “divançe” (mini, incomplete diwan) consisting of poems Ali Amiri has been able to track down. Some of her poems were also featured in Ziya Pasha’s anthology Harabat. Sırrî Hanım passed away in 1877.

¹ Translator’s note: ‘Hanım’ is a respectful term of address added after women’s names in Turkish, meaning ‘lady’, ‘madam’ – the male equivalent of which is ‘bey’.

İffet Hanım

The older sister of Poet Sırrî Hanım, İffet Hanım was named Hatice (Khadija) at birth. Her exact year of birth is unknown. She became one of the well-educated women within the context of her time thanks to her family. It is known that she engaged in “mushairas” (poetry recitals) and “mubahasas” (debates, discussions) with Shaban Kami Effendi, one of the city’s notable scholars, where her knowledge and prowess was lauded. Her spouse, Azmizâde Hafiz Mehmed Effendi was also part of the intellectual and artistic elite of Diyarbakır.

Although we know she had a diwan of her own poems, this is no longer available today. She also had poems that she composed with her sister Sırrî Hanım. İffet Hanım passed away in 1860.

Ekrem Cemilpaşa

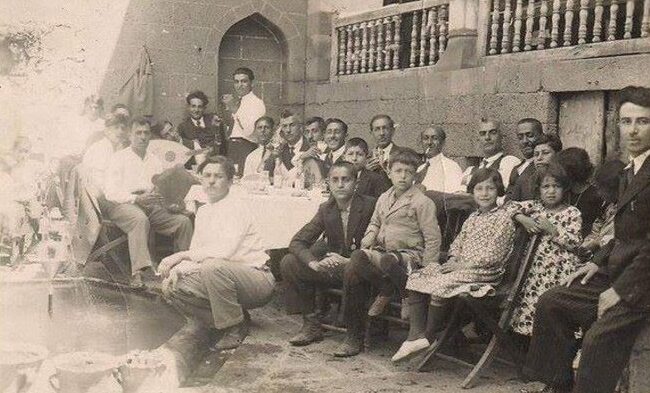

Born in Diyarbakır in 1891, Ekrem Cemilpaşa belonged to one of the prominent families of the city – the Cemilpaşazades. After finishing the Diyarbekir Military Junior High School (1908) and Galatasaray High School (1912) he joined the membership of the newly founded Kürt Talebe-Hêvî Cemiyeti (Kurdish Students’ Hope Society), the first Kurdish students’ organization in history.

World War 1 broke out while he was away at university in Lausanne, Switzerland, causing him to cut his education short and return home. He fought in Gallipoli and was then sent to the Eastern front, where he was wounded. He served as second-in-command of a military base in Diyarbakır and as cipher officer to Mustafa Kemal. He was at the Palestinian front when the war ended, after which he came back to his city. He spearheaded the founding of the Kürt Teali Cemiyeti (Society for the Rise of Kurdistan) in 1918, and the Kürt Teşkilat-ı İçtimaiye Cemiyeti (Kurdish Society for Social Organization) in 1920 that aimed to create an independent state in his region. Though informants turned him in while he was on visits in Anatolia for this work, he was acquitted of all changes. Later on, however, he was arrested during the Sheikh Said Rebellion and sent to the Kastamonu Prison, from where he was transferred to Istanbul in 1928. He crossed over to Syria in 1929, where his life in exile in Damascus – that was to last until his death in 1974 – began. His life was one marked by struggle at every turn.

Cemilpaşa’s Muhtasar Hayatım (A Brief Account of My Life) was printed by Beybun Publishing in 1992. Among his works are: Hînkerê Zimanê Kurdî, Rehberê Ziman ê Her Du Kurdî: Kurmancî, Babanî (Kurdish Language Education, Guidebook for Both of the Two Kurdish Dialects: Kurmanji and Babani,1921), and Dîroka Kurdistan Bi Kurtebirî (A Short History of Kurdistan, 1972). Although Cemilpaşa is mostly known as a political personage, his intellectual pursuits stemming from this political position gave him an important standing in the cultural life of Diyarbakır and in Kurdish culture in general. Along with his widely-appreciated contributions as a historian, Cemilpaşa also wrote profusely in the cultural domain with his dedication to language. He is known to have written poetry as well.

The Cemilpaşazades were influential in the cultural life of the city as a family. Many of their members, with Ekrem and Kadri Cemilpaşa as primary examples, received their early education in the family mansion, from notable scholars of the city. They crowned this with a higher education abroad, applying the learning they acquired to regional politics, as well as in their contributions to the arts and culture of the city, which left a mark that lasted over generations.

Ashik Melul

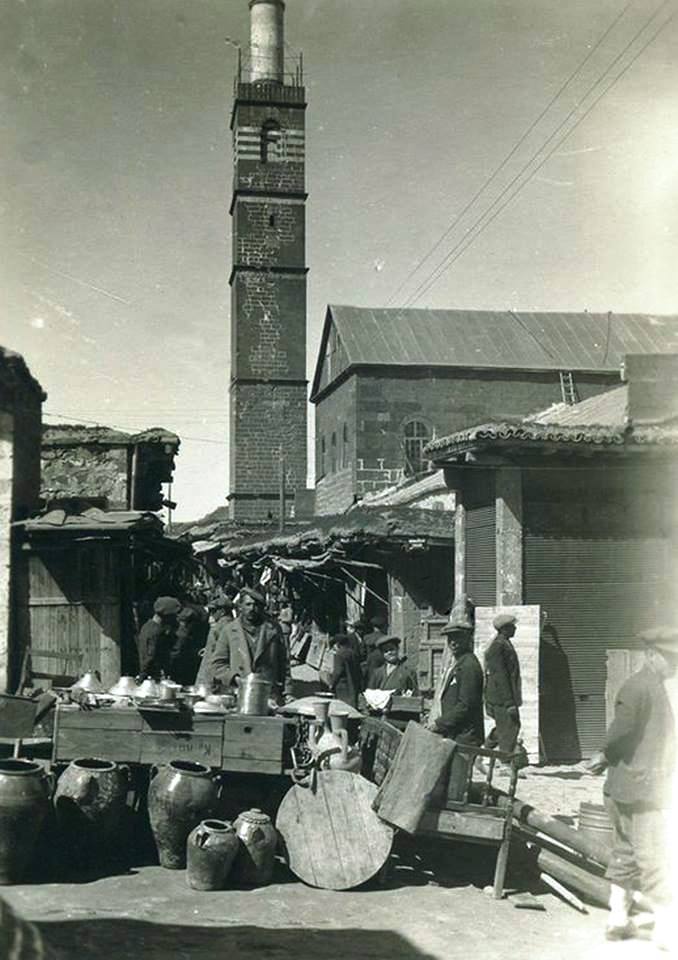

Born Levon, this ashik (singer-poet/bard) grew up apprenticing under his father Ermush Effendi, a master puşi and mantin weaver like many Armenians. Over time, he went from apprentice to foreman. In 1895, fires breaking out during Armenian protests in the time of Vali (Governor) Enis Pasha ravaged hundreds of shops particularly in the Cami Kebir (Great Mosque) quarter. When the blaze came through the Sipahi (İspahi) market, it left behind neither weaving loom nor a scrap of fabric to weave. After this incident the market was dubbed “Çarşiya Şewitî” (Burnt Market).

In his encyclopedia titled Diyarbakırlı Fikir ve Sanat Adamları (Intellectuals and Artists of Diyarbakır), Şevket Beysanoğlu features a rumor about Ashik Melul: Allegedly the ashik was killed due to a destan (traditional epic) he composed satirizing the leaders of the incidents of 1895. The epic itself, however, has not reached our day.

In a known folk song of his Ashik Melul says:

Not a moment of joy, sorrow’s here to stay

Ever since my dark-eyed beauty’s gone away

O creator almighty deliver me I pray

Melul¹ ashik, through the path of fire finds the way

¹ Melul: Sad.

Fatma Bacı

One of the few woman saz poets (poet-singer) in history, Fatma Bacı’s¹ birth name and year remain a mystery. She is a member of the Dalkabak family of Diyarbakır. What has reached our day from her works are an epic/saga, a lament and a lullaby. Her Karakış Destanı (Saga of the Dead of Winter) on the arduous winter of 1886-87 also serves as an important document as to how a certain period was experienced in the urban history of Diyarbakır.

In the calendar year three hundred and two

Frozen fruits on trees, a cold so blue

Hens and roosters dying in the coop

Everyone wearing boot instead of shoe

O Lord! Deliver us from this cold.

(…)

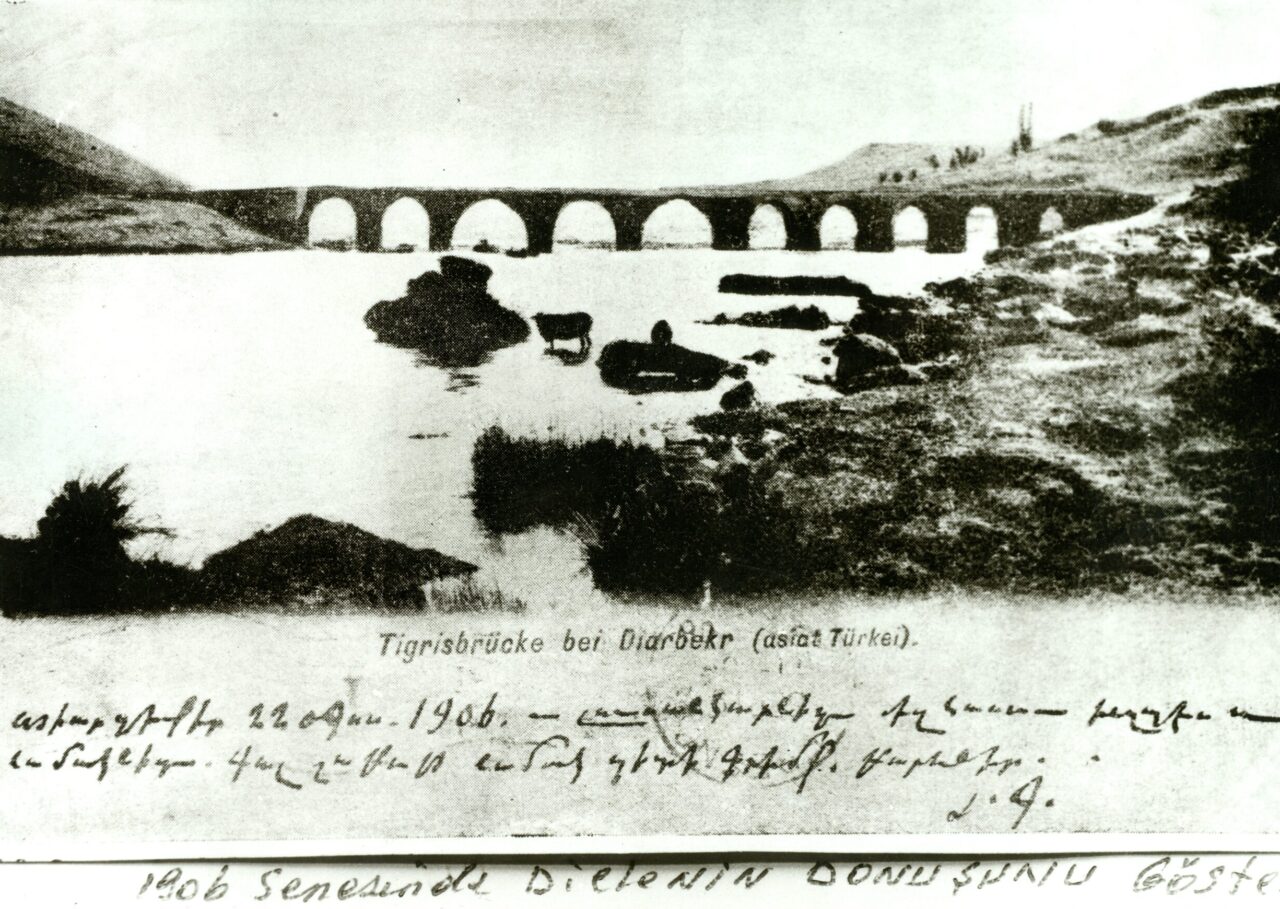

The Tigris River ‘tis but a chunk of ice

Rumi’s night of reunion went by with rites

Everywhere they promised ‘twould suffice

But wood and coal’s never a cheap price

O Lord! Deliver us from this cold.

The date of Fatma Bacı’s death is also unclear, yet she is thought to have passed away sometime in the years 1895, 1896 or 1897.

¹ t.n. Though ‘bacı’ means ‘sister’ in Turkish, it is also added to women’s names even when they aren’t necessarily relatives to indicate a sense of familial respect.

Sami Hazinses

While Turkey knew him as Sami Hazinses, for the people of Diyarbakır he was Samo. He featured in more films than even he himself could remember, mostly in supporting roles, and was known as a true powerhouse of Yeşilçam.¹ However, ever since his early youth, it wasn’t only acting, but also music that had an important place in his life. Many of his melodies and lyrics became popular classics, picked up by the likes of Zeki Müren, Müslüm Gürses and İbrahim Tatlıses.

His name at his birth in the village of Herêdan (Kırkpınar) in Diyarbakır’s Pîran (Dicle) district in 1925 was Samuel Uluçyan. Writer Şeyhmus Diken notes that his father Mıgırdiç Uluçyan was known as “Marshal” for having survived the Genocide of 1915.

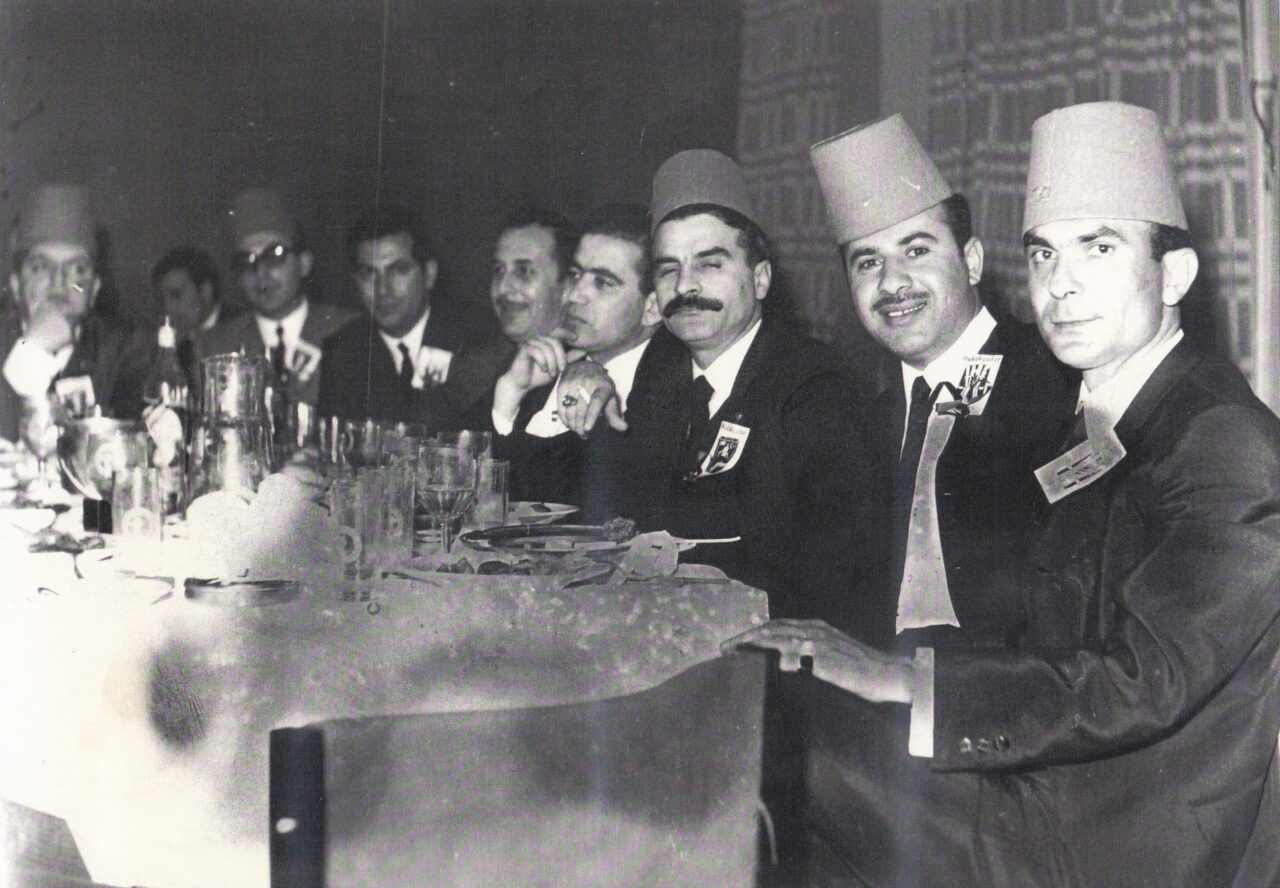

Hazinses spent his youth in the neighborhood of Hasırlı, formerly known as Hançepek, where his family moved in his childhood. On the one hand working as a puşi weaver like many of the Armenian artists and artisans of the city, on the other he joined the Diyarbakır Music Association (Diyarbakır Musiki Cemiyeti) conducted by Celal Güzelses, an important figure in the musical history of Diyarbakır. By the age of 26, he and his close friends violinist Hüsnü İpekçi and cümbüş player Sobacı Antranik had made a name for themselves in the musical circles of the city.

When he migrated to Istanbul in order to start a new life in 1950, his first step was to seek out his Armenian friends in the film industry, Danyal Topatan and Vahi Öz (Vahe Ozinyan). With the well-justified concern that it would impede his career at Yeşilçam, he gave up his Armenian name. Inspired by his musical teacher Celal Güzelses, he took on the name Sami Hazinses.² After a minor role in the film “Kara Davut” (“Black Davut”) he would act in countless supporting roles and compose for various films until he suffered from a brain hemorrhage in 1994.

Sami Hazinses, or let us rather say Samuel Uluçyan, passed away in a nursing home in 2002.

¹ t.n. Literally meaning the ‘Green Pine’, Yeşilçam is a metonym that stands for the classic Turkish film industry, being the name of the street where most studios, actors, etc. used to be based.

² t.n. His teacher’s name ‘Güzelses’ means ‘beautiful voice’ in Turkish, while ‘Hazinses’ means ‘sad voice’.

Melek Tigrel

Born in 1919, poet Melek Tigrel is the daughter of prominent politician İhsan Hamid Bey of the Tigrels, one of the city’s long-standing families. She started her studies in Diyarbakır and continued in Istanbul where her family settled at a later date. Her interest in literature was already apparent in high school, where she would write poems. She had sent some of these in letters to Cahit Sıtkı Tarancı, whom she had met through their families’ connection. From letters that Tarancı wrote to Ziya Osman Saba in 1942, it was clear that their communication wasn’t limited to this, and that in fact Tarancı had been influential in Tigrel’s choice of enrolling in the Istanbul University Department of French Language and Literature. Thought to have much in common and much to share, these two poets were encouraged by their families to marry. Tarancı’s rising excitement was evident from his letters to Saba:

“Her demeanor, her conduct, the way she speaks, her sense of ease coming from a certain gravitas, and most of all the bold interest she showed me simply enchanted me. If you were there, you would most certainly have said, Cahit is about to soar with delight. Yes, indeed he is over the moon, high as a kite… She read me some of her poems, spoke about books she had read, listened to my poetry, even took the time to transcribe some of them. (…) She recited some of her prose as well, all from memory. Let me give you a line of hers I liked: ‘So deep inside of me are you that I catch myself about to call you ‘me’ instead of ‘you’!’”

Tarancı also supported Tigrel in getting her poems published, some of which later appeared in certain issues of the Varlık magazine. With a year left to her graduation from university, Tigrel married Muammer Öktem, a foreign trade consultant working in the Ministry of Trade. They moved to Rome for his job.

Tigrel’s correspondence with her relative Faik Ali Ozansoy¹ provides a crucial insight into the sociocultural life and literary gathering places of the period. Her poem “Yankı” (“Echo”) was published in the Anthologie de la Poésie Féminine Mondiale’de (World Anthology of Women’s Poetry) in Paris in 1973. Investigative writer from Diyarbakır Reşit İskenderoğlu’s 1995 book titled Zarif Bir Şaire (An Elegant Poetess) offers information on Tigrel’s family as it does on her poetry and life.

¹ Selahattin Çitçi (ed.), Hanım Kızım Kıymetli Şairem [Dear Daughter Precious Poetess], Akademi Titiz Yayınları, 2018.

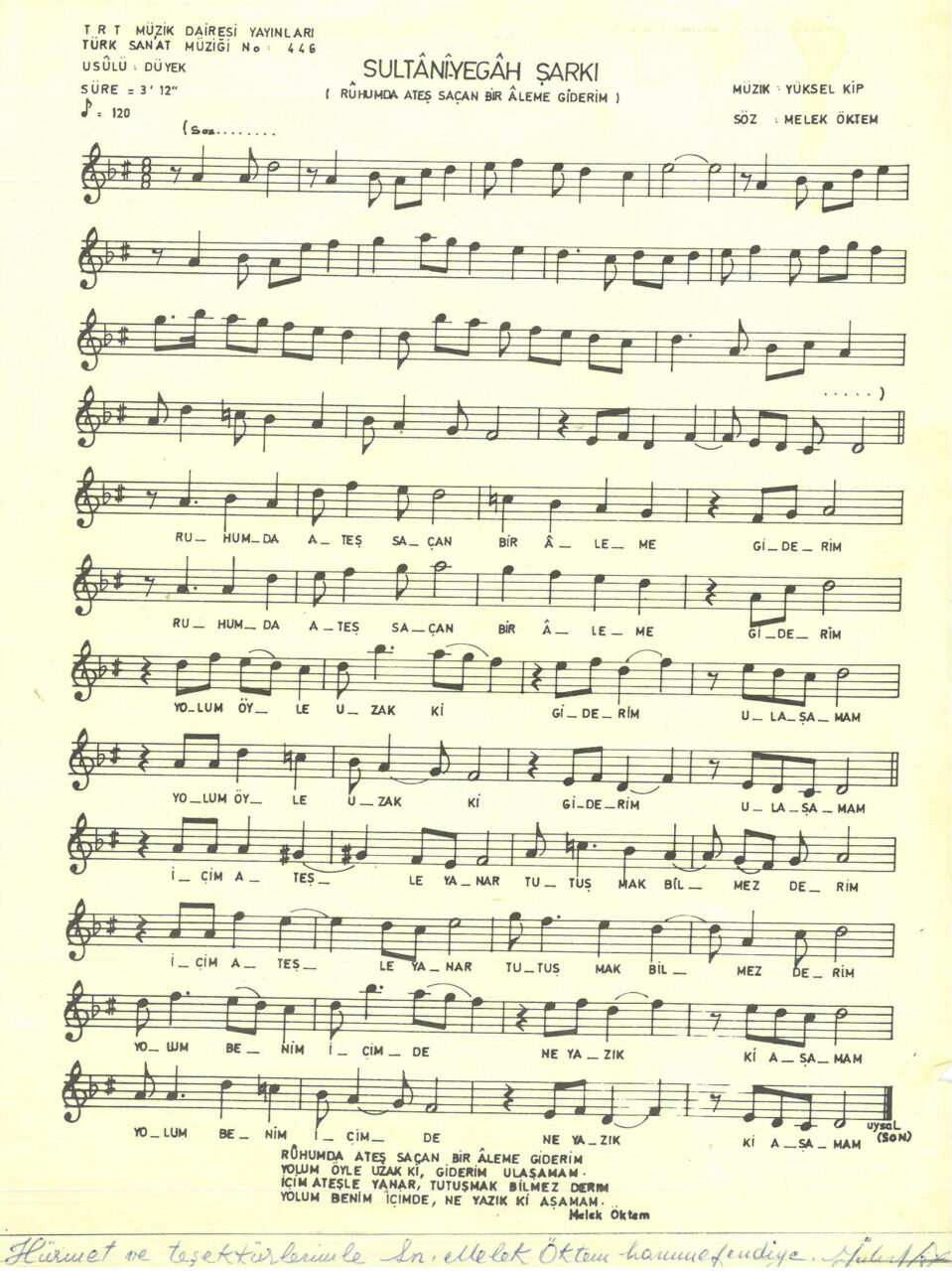

Poet from Diyarbakır Melek Tigrel’s poem “Ideal” was set to music by Yüksel Kip. Composed in the Sultaniyegâh maqam, the song was aired on TRT Radios.

Bound for a land that sets my soul aflame

So far away, it’s there but out of reach

I burn deep inside, without a blaze

My path is within me, impossible to unleash.

İhsan Fikret Biçici

One of the first to come to mind when speaking of the poets of Diyarbakır, İhsan Fikret Biçici was born in 1936. He studied law. His interest in literature formed while he was yet a student, and his first poems and writings were published in the Çizgi magazine in 1953. He worked with Ahmed Arif at the copy-editing desk of the Öncü newspaper. His poems were published in many arts and culture magazines while he worked as a lawyer, and he never severed his close ties particularly with Diyarbakır-based magazines such as Yaratım, Palto, and Pitoresk up to his dying day. He was on the inside team of the magazine Amida, and also served as chair of the Diyarbakır Poets and Writers Association (Diyarbakır Şair ve Yazarlar Derneği) founded after 1980 and the Diyarbakır Association for the Protection of Cultural and Natural Assets (Diyarbakır Kültür Tabiat Varlıklarını Koruma Derneği – DKVD).

Biçici wrote poems that circulated widely in Diyarbakır and were on everyone’s tongue. Though his love for Diyarbakır shines through in many of his verses he was more than a simple town poet. He was a master at bringing his local context into the universal sphere of poetry. Here is what he said in an interview with Suzan Samancı,¹ also a poet and writer from Diyarbakır:

“I’ve always been drawn to poems marked by love and beauty rather than to poets themselves. To me, it doesn’t matter which poet that poem may belong to. A lovely evening, a calm and quiet night, a flower, a tree, a warm glance, a trustworthy friend’s hand – these are what touch me deeply, and poems in which these are reflected of course. Perhaps for this reason I’ve never been able to bear animosity, never wished ill on someone, even if they did on me. I never tried to emulate another poet – nor did I have the desire to.”

İhsan Fikret Biçici was one of the main characters of the novel Ben û Sen.² He passed away in 2013. His three books of poetry, Şıpka’ya Mektuplar (Letters to Şıpka) (1997), Vay Limin (Woe is Me) (1997), Adınla Vurulup Ölmek (Shot Dead by Your Name) (2004) were compiled into one in his Bütün Şiirleri (Collected Poems).³ DİTAV (Diyarbakır Tanıtma, Kültür ve Yardımlaşma Vakfı / Foundation for Culture, Cooperation and the Promotion of Diyarbakır) started granting poetry awards in İhsan Fikret Biçici’s name in 2022.

¹ Gündem, 19 September 1997.

² Ahmet Çakmak, İletişim Yayınları, 2019.

³ Öncü Yayınları, 2009.

Gani Bozarslan

Poet and translator Gani Bozarslan was born in Diyarbakır’s district of Lice in 1952, as the son of writer, researcher, translator Mehmet Emin Bozarslan, an important personage in Kurdish cultural life. At the age of ten, he moved to Istanbul with his family. Sadly, Gani Bozarslan died at a very young age in 1978, in circumstances that remain unclear. The connection between his political identity and this sudden death has often been made.

Along with his poetry, Bozarslan was also an accomplished translator. With Lenin Şafağı (Lenin’s Dawn), a collection of Cigerxwîn’s poems, he effectively brought this Kurdish master poet into the Turkish language for the first time. He also translated into Turkish the grand Kurdish epic Memê Alan, Erebê Şemo’s Şivanê Kurd (Kurdish Shepherd) – considered the first novel in Kurdish literature, and various poems by Feqîyê Teyran, pioneer of Kurdish classical poetry.

Gani Bozarslan’s works Silahım Kalemimdir (My Pen is My Weapon) and Parti Günışığı Nardalı (Party, Daylight, Pomegranate Branch) were published in 1979.

as when flesh touches ember

so too your heart hisses, I know

but don’t let rage double-load your barrel

for with the dawn breeze

this spring spins its web

though the grub is moldy

and the milk’s gone sour

blood is no stranger to your quickening pulse

and now, the time is upon us

to take your raw, exposed poem

out of the box of odd creatures

time to water the poplars

and in spite of those of sickly breath

their spit dry in their mouths, we say

in spite of those who are used to being herded,

in the cattle pens of life,

we begin whetting

a dagger already sharp of blade

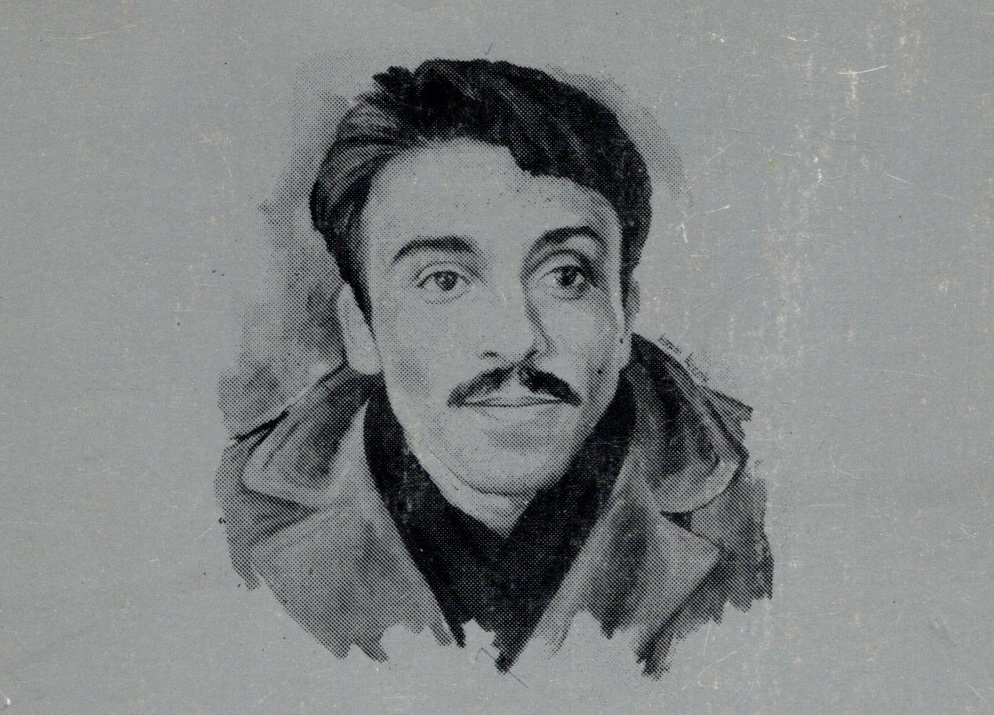

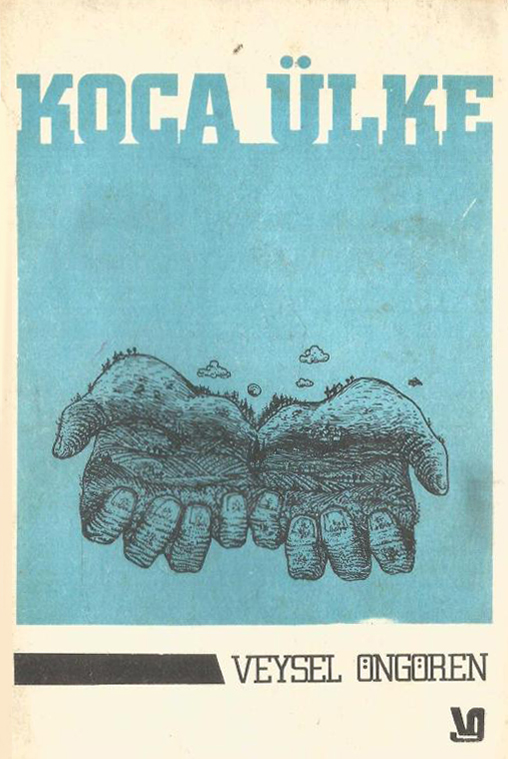

Veysel Öngören

Born in 1931 in the village of Hacikan in Diyarbakır’s Bismil district, poet and writer Veysel Öngören is the older brother of caricaturist-writer Ferit Öngören and writer, actor and director Vasıf Öngören. Öngören completed the greater part of his studies in Kütahya and Afyon, where his family had been resettled due to antagonisms between Kurdish tribes in the region. He dropped out of the Istanbul University Faculty of Literature, Department of Turkish Language and Literature where he was studying to return to Diyarbakır and spent the latter half of the 1950s in his village. In 1959, he entered the Ankara University Faculty of Language, History and Geography, Department of Philosophy, from where he eventually graduated. His home destination was once again Diyarbakır.

Öngören worked in the Vatan newspaper and the TRT Foreign News Service, but literature was always his main passion and occupation throughout his life. He burned all the poems he wrote until the age of thirty. In 1960, he entered the literary world with writings he published in the Dost magazine and later Yeni Ufuklar magazine in Ankara. His first book of poetry was published in 1979. Along with poetry, he continued writing essays on Turkish literature as well.

He worked for while in the management of Ankara Birliği Sahnesi (Ankara Union Theater), founded by his brother Vasıf Öngören. Veysel Öngören then became artistic director of the Diyarbakır City Theater, serving here from the early 1990s until his death. Countless actors achieved success in theater and cinema with the training they received from him. He had a way of teaching you about “life” itself, alongside his areas of formal education such as aesthetics and philosophy.

Öngören passed away in 1998 in his village where he had been farming. The words “child, flower, window” from a poem of his are indeed a perfect summary of his life.

Poetry books: Remo ve Salo (Remo and Salo) (Türkiye Yazıları, 1979), Vay Gözüm (Oh, My Dear) (Türkiye Yazıları, 1981), Remtelebe (Türkiye Yazıları, 1982), Koca Ülke (Big Old Country) (Türkiye Yazıları, 1983), Arif’in Kızı (Arif’s Daughter) (Memleket Yayınları, 1987)

Prose: Şiir ve Yenilik (Poetry and Novelty) (Broy Yayınları, 1997)

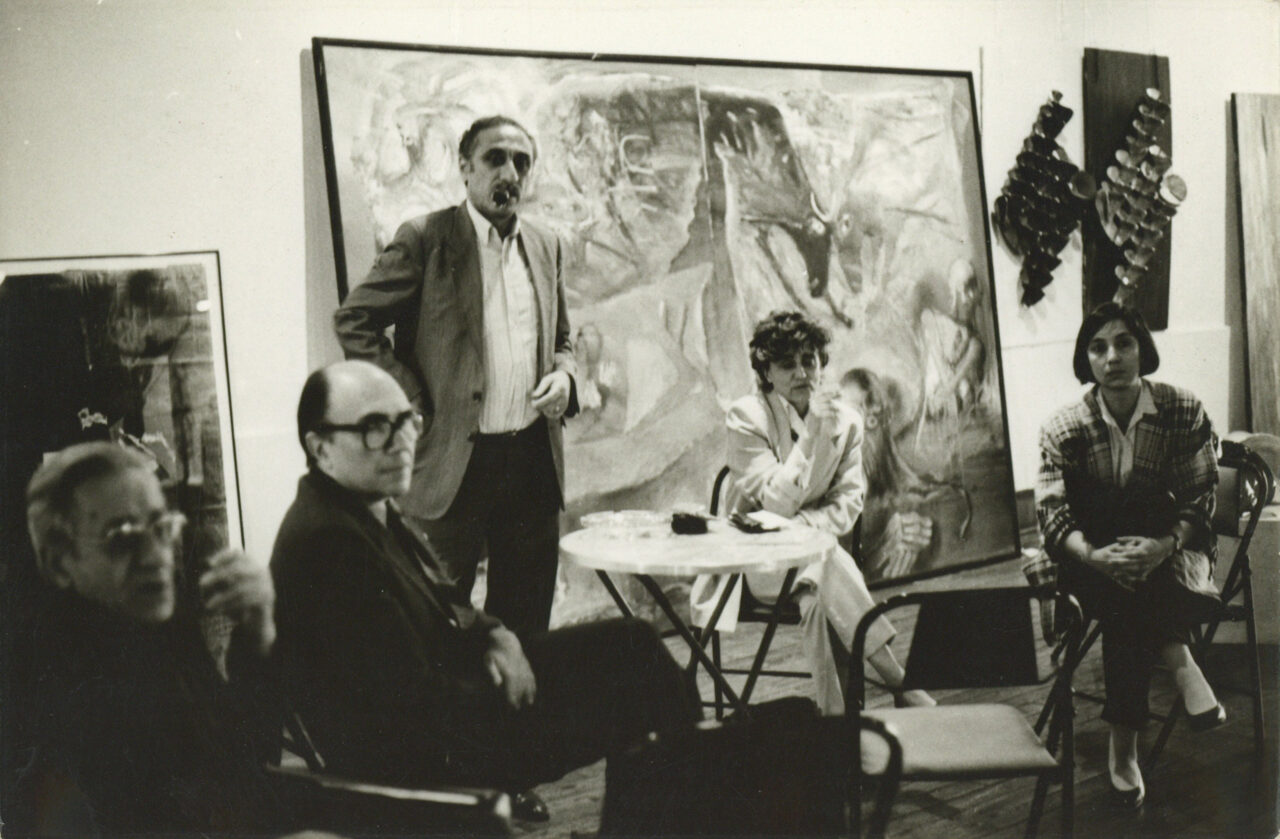

Kaya Özsezgin

Painter, professor of art history, writer, translator and critic Kaya Özsezgin was born in 1938. After finishing his primary and secondary education in Diyarbakır, the city of his birth, he studied at the Ankara University Faculty of Language, History and Geography, Department of Art History. Upon graduating, he taught art history and painting in various schools. He then started as teaching assistant in the Hacettepe University Faculty of Fine Arts in 1984. By 1996, he had become a professor and served as dean of his faculty.

Özsezgin also drew for the Yudum magazine published by Canip Yıldırım in Diyarbakır in 1957. After three painting exhibitions of his own, he turned to art criticism. He wrote pieces on art in the Vatan and Ulus newspapers, as well as in publications such as Pazar Postası, Sanat ve Sanatçılar, Papirüs, and Milliyet Sanat. He also took on the role of editor-in-chief of the Artist magazine for a while.

Kaya Özsezgin was among the founders of Foundation for Culture, Cooperation and the Promotion of Diyarbakır (Diyarbakır Tanıtma, Kültür ve Yardımlaşma Vakfı – DİTAV). He became the recipient of the Art Institution Award (Sanat Kurumu Ödülü) in 1989, and the 7th Art Fair Award for Art Criticism (7. Sanat Fuarı Sanat Eleştirmeni Ödülü) in 1995.

He left many valuable works in his wake. In addition to encyclopedic compilations of the visual artists of Turkey, he also has monographs on many individual artists such as İbrahim Çallı and Burhan Uygur. In 1998, he published a study titled Cumhuriyet’in 75. Yılında Türk Resmi (Turkish Painting on the 75th Anniversary of the Republic). Having translated many books on painting and art into Turkish, Özsezgin is also the translator of Albert Gabriel’s Diyarbakır Surları (Walls of Diyarbakır) from French into Turkish. He has a book of essays titled Diyarbakır’ı Dinliyorum Gözlerim Kapalı (I’m Listening to Diyarbakır, My Eyes Closed).

Kaya Özsezgin passed away in 2016.

Text: Ahmet Çakmak

Translation: Feride Eralp

We would like to thank Melek Tigrel Öktem and Ayşe Öktem for their contributions.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

• Beysanoğlu, Ş. (1960) Diyarbakırlı Fikir ve Sanat Adamları [Intellectuals and Artists of Diyarbakır], Vol 2, Diyarbakır’ı Tanıtma Derneği, Istanbul.

• Beysanoğlu, Ş. (1992) “Diyarbakır Halk Kültüründe Saz Şairleri Geleneği ve Türkçe Söyleyen Diyarbakırlı Ermeni Aşuglar” [“The Tradition of Poet-Singers in Diyarbakır Folk Culture and Armenian Ashugs of Diyarbakır Singing in the Turkish Language”], IV. Milletlerarası Türk Halk Kültürü Kongresi Bildirileri, Vol 2, Kültür Bakanlığı, Ankara.

• Beysanoğlu, Ş. (1996) Diyarbakırlı Fikir ve Sanat Adamları [Intellectuals and Artists of Diyarbakır], Vol 1, Diyarbakır Tanıtma, Kültür ve Yardımlaşma Vakfı, Ankara.

• Çakmak A. (1991) “Kaya Özsezgin”, Diyarbakır Tanıtma, Kültür ve Yardımlaşma Vakfı Dergisi, 1(1).

• Çakmak A. (1998) “Çocuk, çiçek, pencere” [“Child, flower, window”], Edebiyat ve Eleştiri, 39-40.

• Çeliker, S. (2016) “Öleyim, ondan sonra yaz Ermeni olduğumu: Sami Hazinses” [“Wait till I die, then write I’m Armenian: Sami Hazinses”], Gazete Duvar.

• Diken, Ş. (2013) “Sahi, Sami’nin Sesi Neden Hazin’di!” [“Why Indeed was Sami’s Voice ‘Sad’!”], Bianet.

• Şenyapılı, Ö. (2019) “Cahit Sıtkı Tarancı”, Niteliksel.

• Tarancı, C. S. (2001) Ziya’ya Mektuplar [Letters to Ziya], Varlık Yayınları, Istanbul.

TEACHING, DOCUMENTING