The Upper Tigris Basin, lying in the upper-middle reaches of the “Fertile Crescent” has always been a center of attraction, throughout history and prehistory, as a veritable crossroads of Mesopotamia, Syria, Iran, the Mediterranean and Anatolia, the east and the west, the north and the south. With an identity forged by its location in this basin and the Tigris River, Diyarbakır has been marked by most all dynasties and nations to have ruled in Anatolia and Mesopotamia – be it for a couple of years or a couple of centuries, and it is with this abundance of cultural accumulation that the city has reached our day.

One feature rendering Diyarbakır significant within the framework of universal cultural history is Körtik Tepe, a site that opened a new page in Anatolian archaeology. Located in Diyarbakır’s Bismil district at the confluence of the rivers Batman (Batman Çayı) and Tigris, Körtik Tepe is dated back to the pre-pottery Early Neolithic (10400-9250 B.C.), a time when the hunter-gatherer way of life was still predominant.

Körtik Tepe provides a unique example as one of the first sites portraying a Neolithic community’s organization in sedentary life and the effects of subsistence activities on this lifestyle. Stone mortars and grinding slabs point to an advanced production level supporting a gathering subsistence strategy. As such, Körtik Tepe demonstrates a pioneering subsistence and settlement pattern that renders Göbeklitepe’s (in Şanlıurfa) spectacular symbolic-monumental level less of an exception in its time. A settlement with intense fishing activity as well, Körtik Tepe also contains architectural structures for food storage purposes. Their presence is a manifestation of the development of production technologies to this end, and of the existing social and economic organization. There is also evidence of knowledge of weaving at Körtik Tepe.

The settlement phase dated to 9300-6300 B.C. at Çayönü located 7 km east of Ergani represents an important step towards our present-day civilization as one of the earliest examples of the shift from hunting-gathering to an agricultural food production economy. It is known that plants such as wild wheat and legumes were cultivated, and sheep and goat were domesticated at Çayönü. The fact that copper was heated and moulded into shape – even manufacturing beads and objects of the sort – two thousand years before it was discovered and worked in other parts of the world renders Çayönü special. Its physical proximity to the Ergani mines, home to the world’s oldest copper deposits, is the most important factor in this success.

Çayönü is also one of the rare settlements where the architectural development leading from the Neolithic Period to advanced village life may be seen in all its phases. The transition from simple stick-framed, circular huts plastered with mud to adobe constructions much like our present-day village houses, built on stone foundations with door and window openings is, in particular, one that manifests traces of this entire process.

The reliefs and inscriptions by Tiglath-Pileser I (1114-1076 B.C.) in the Bırkleyn Caves, known as one of the sources of the Tigris located at a 1.5 km distance to Lice’s Abalı Village, are among the best-preserved, most visible remains in our day. Some of the five caves in the region are known to have been used from the Late Neolithic onwards (4th-2nd millennia B.C.) into the Iron Age due to their strategic position. The Diyarbakır-Bingöl route upon which the Bırkleyn Caves are located used to function as the easiest pass through the Taurus Mountains between Eastern Anatolia and Northern Mesopotamia in ancient times. This road along the Dibni Stream, known as the eastern branch of the Tigris, was also an important trade route. Assyrian kings Tiglath-Pileser I and Shalmaneser III wishing to establish their control over the region had inscriptions and reliefs made in the caves due to this special location of theirs – as if in an effort to inspire a sense of security in merchants using this route. Bırkleyn’s conquest is also depicted in the bronze bands adorning the famous Balawat Gates constructed 28 km southeast of Mosul during the reign of Shalmaneser III.

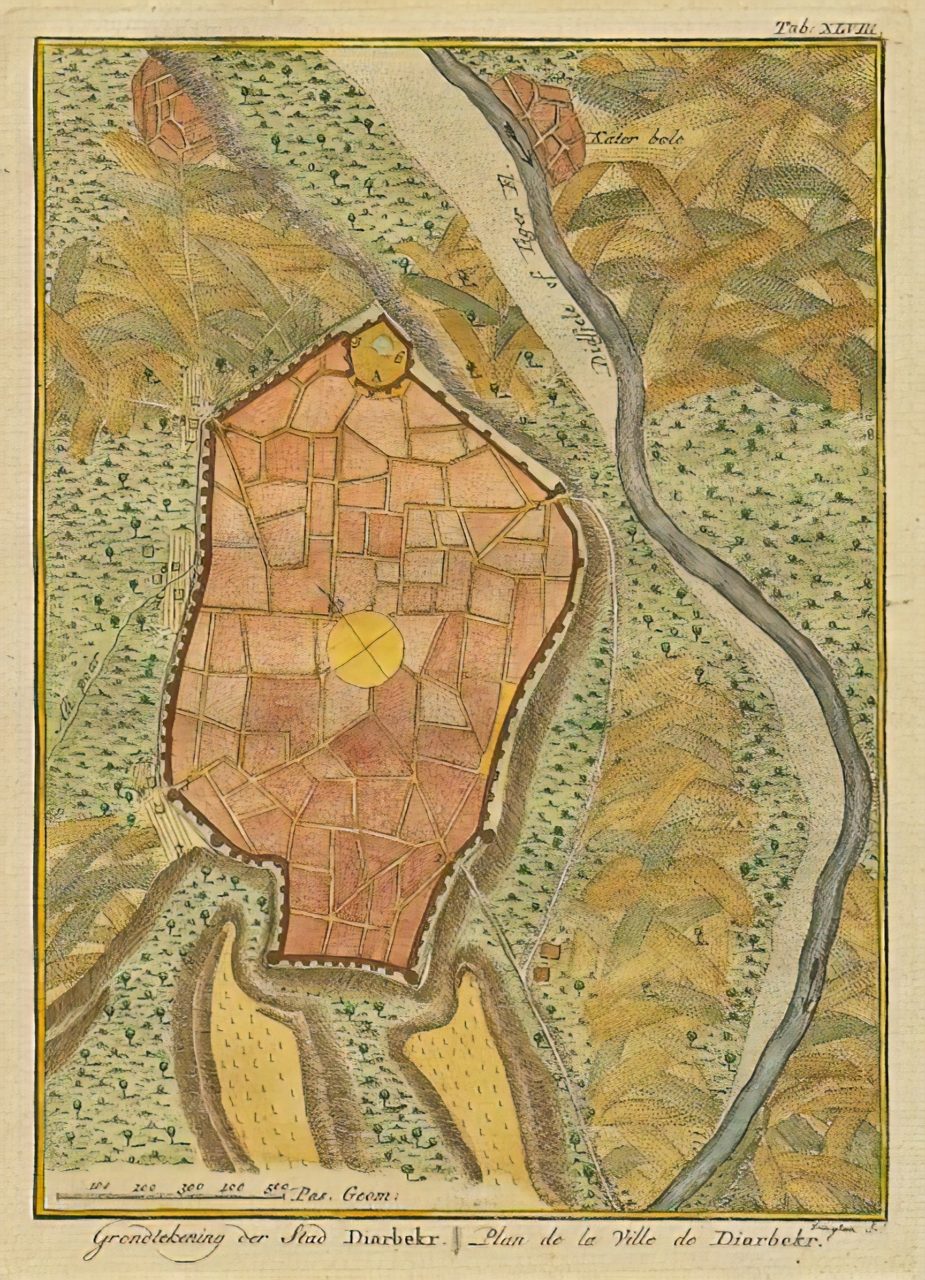

The city was established on a basalt plateau in Amida Höyük, in close proximity to natural water sources, with ample arable land, in an easily defensible position commanding the Tigris River and its valley. This position and conditions were crucial for the persistence of settlement and its development in its original site. Its location at a crossroads of ancient routes also made it an important commercial and agricultural center throughout history.

Finds from surface surveys at Amida Höyük date the earliest traces of settlement on the site to somewhere between 4200 and 3800 B.C. Handmade pots found here suggest that this oldest settlement was inhabited by a local community. It is possible that a lower city existed around the mound (höyük) in the Uruk period, and that the settlement extended to today’s İçkale (Citadel/Inner Fortress). Layers belonging to the Hurrian-Mitanni period of 2nd millennium B.C. were also discovered in the mound.

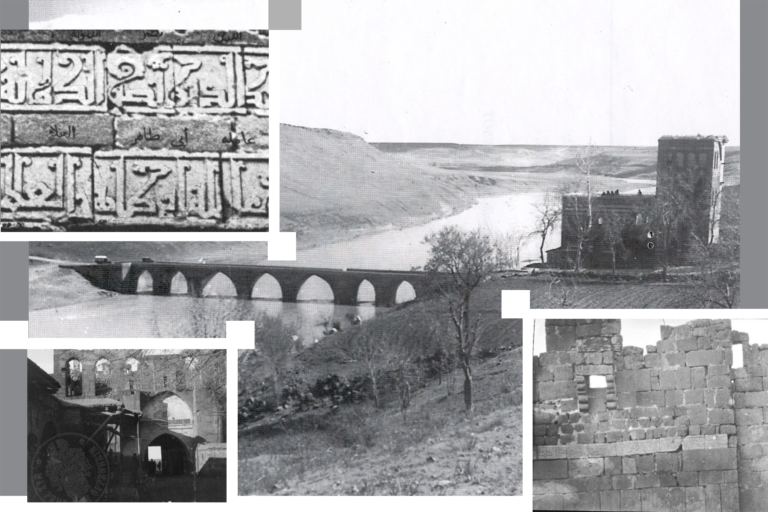

With the decline of Assyria, Aramaic migration was drawn to the banks of the Tigris in 1050 B.C. Diyarbakır, then known as Amida, also featured in the Roman-Persian conflict due to its strategic position and rich water sources. Roman Emperor Constantius II had chosen the place as a garrison town while battling the Sassanians circa 330. Following a siege of the city lasting 73 days by Sassanid ruler Shapur II with an army of one hundred thousand, Constantius II built the famous walls that still give the city its character even today, all the way in the 21st century. Made of black basalt stone, these walls were then repaired by Valens in 370. The next serious invasion took place in 502-503, when Sassanid ruler Kavadh I took the city with a force of fifty thousand soldiers. Yet Anastasius recovered it for the Romans in 505. Justinian I was to then have the city restored and rebuilt after the year 532.

Captured in 639 by Iyad ibn Ghanam, charged by Caliph Umar with the conquest of the al-Jazira (Mesopotamia) region, the city came under Muslim Arab rule. A small troop of soldiers was stationed in the city during the Umayyad period in order to preserve security and order and collect taxes. In 863, the Eastern Romans mounted a campaign to the region. In 868, Isa ibn al-Shaykh, governor under the Abbasids, rose up against the Abbasids with the support of his tribe the Shaybani Arabs densely populating the eastern banks of the Tigris, founding an autonomous emirate named “Şeyhoğulları” – “the Shaykhs”. His son Muhammed was governor of Amid. Ruling over the region for around thirty years, this emirate was eventually brought to an end in 899 with a siege by Abbasid Caliph al-Mu’tadid (Mutazid) Billah. In 911, the Eastern Romans once again rode out to the area and captured Egil and surrounding forts.

As his authority over the provinces weakened vis-a-vis Eastern Roman attacks, Abbasid caliph al-Muqtadir handed the region to the most prominent member of the Shi’a Arab Hamdanid dynasty, Sayf al-Dawla, in 931. Fighting against the Eastern Romans for years on end, the Hamdanids sought to expand their territories all the way to Malatya. The Romans, on the other hand, attempted five sieges on Amid in thirty years after 936, but none were successful.

As of 984, the Diyarbekir region came under the rule of Harbohti Badh of the Bohtan Kurds. The near-century-long rule of the Marwanids in Upper Mesopotamia, which in many ways constituted a unique episode in the city’s history, thus began. (“A parenthesis in history: the Marwanids”)

Although the Marwanids had fought alongside the Seljuqs in the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, the prosperity of their lands still drew the hostile attention of the Seljuq Empire. Besieged under the orders of Sultan Malik Shah, the city was captured in 1085. With his appointment of a governor named Inal, the Inalid Principality (Beylik) that would hold sway over the region for almost a century was founded.

The vizier of the Inalids, Nisanid Ali had begun to gain notoriety for his maltreatment of the people. While Fakhr ad-Din Qara Arslan (or Kara Arslan), ruler of the neighbouring Hisn Kayfa (Hasankeyf) branch of the Artuqids, had made dozens of attempts to take Amid in order to put an end to these troubles, none had succeeded. His son Nur al-Din Muhammad asked for support from Ayyubid Sultan Saladin (Salah al-Din) in order to bring his father’s wish to pass. In return, he pledged his soldiers to Saladin’s army in wars to come.

The giant mangonels (or trebuchets) of the Ayyubid army, called by the name of “al-Mufatti” (El-Müfettiş) pounded the black basalt stone of the city walls for days on end, and in 1183 the city was finally taken. Its bastion towers were full to the brim. Nearly eighty thousand candles had been stashed in one alone, while another held arrowheads and stacks of grain sacks. The city’s vaults were also full of bales of cotton, bolts of fabric, carpets and tents. Sultan Saladin granted the enormous one-million-forty-thousand-volume library to his secretary/scribe Qadi al-Fadil. As promised, Sultan Saladin Ayyubi left Artuqid Nur al-Din Muhammad in charge of the city. The Mesûdiye Madrasa and Zinciriye Madrasa were built by his son Sokman II, who replaced his father after his death. Sultan Saladin had silver and copper coins minted here in his name for many long years as a marker of his sovereignty.

(For a reading of the city’s history through coins, check: “Diyarbakır as told in coins”)

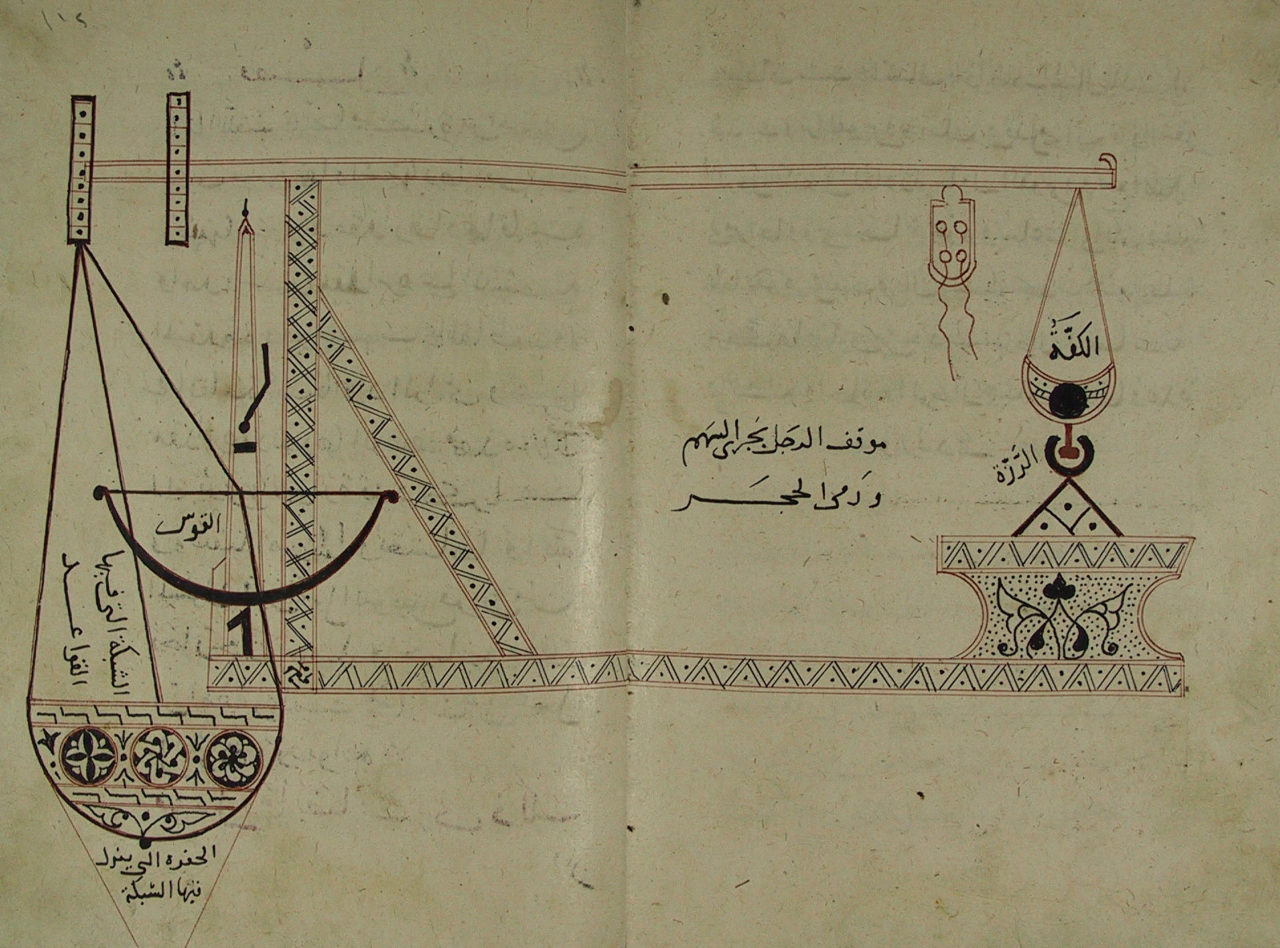

A wealth of building activities for public improvement were undertaken in Amid during the reign of al-Malik al-Salih Mahmud, who ascended the Artuqid throne after his brother Sokman II. New towers were added to the walls, and a palace constructed in the citadel. One of the factors lending particular significance to this period was the presence of Abu al-‘Izz al-Jazari, whose works and achievements in the field of mechanics brought him fame that lasted from the Middle Ages up to the present. Having served two Artuqid rulers, father and son, for a quarter of a century, Al-Jazari’s philosophy of engineering as well as his three-dimensional machines and inventions provided an example that would inspire and guide many others from the East and the West to follow in his footsteps. He compiled most of his mechanical devices in his treatise titled “Kitab al-Jami’ bayn al-‘ilm wa-‘l-‘amal al-nafi’ fi sinat’at al-hiyal” (originally translated as “The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices”, also known as “A Compendium on the Theory and Useful Practice of the Mechanical Arts” or “Work that Combines Theory and Practice and Is Profitable to the Craft of Ingenious Contrivances”).

Al-Malik al-Mas’ud Maudud, who became ruler of the Artuqids in 1222, gained quite a reputation for his hostile attitude towards his own people as well as his neighbours. It is for this reason that about a decade later Ayyubid sultan al-Malik al-Kamil II deposed him and retook control of Amid. Though the city briefly came under the control of Ruler of Mayyafariqin al-Malik al-Kamil in 1257, Hulagu Khan took the situation in hand in 1259 and gave it back to the Seljuq Sultanate of Rûm, who were vassals of the Mongols. The Mongols thus came to hold sway over the entire Diyarbekir region.

In 1303, Ghazan Khan put Najm al-Din Ghazi II, ruler of the Artuqids of Mardin in control of the region, and in 1317 a huge revolt broke out in the city. Mongolian raids from the southwest and the looting and pillaging these involved came first among the reasons behind this outbreak. Additionally, life in the city had become unbearably expensive, forcing many villagers to abandon their fields and move elsewhere, and the tax burden on the Christian population had increased. The uprising was quashed by Artuqid Sultan Shams al-Din Salih, yet the city suffered serious damage in the process. A year later would come a great famine.

Captured and plundered by Tamerlane (Timur) in 1394, the city was then handed over to Qara Osman (Kara Yülük Osman Bey) in 1401, thus marking the start of Aq Qoyunlu (White Sheep Turkomans) rule over the region. Though Qara Qoyunlu (Black Sheep Turkomans) leader Qara Yusuf made numerous attempts on the city at the outset of the 1400s, all were to no avail. His son Qara Iskander met the same fate in 1423, and so did Egyptian Mamluk Sultan Barsbay in 1433. Upon Qara Osman’s death in 1435, Amid passed into the hands of Aq Qoyunlu princes and became scene to their rivalries and competition for power. The Qara Qoyunlu also laid siege to Amid a couple of times during Jahangir Beg’s reign over the city, yet were unable to take it. Specimens of Aq Qoyunlu architecture, the Sheikh Matar (Mutahhar) Mosque built by Sultan Kasım in 1500 and named after the sheikh buried in the site and the Four-legged Minaret belonging to the mosque are still among the city’s landmark structures.

When the entire Qara Qoyunlu territories were conquered by the Aq Qoyunlu under Uzun (“Tall”) Hassan Beg’s leadership, the Aq Qoyunlu capital was moved from Amid to Tabriz. Yet Amid retained its place as the Aq Qoyunlu Confederation’s main seat in the west due to its strategic importance. During a campaign led by Shah Ismail against Ala al-Dawla of the Dulkadir (Dhu’l-Qadr) confederation in 1507, Emir Beg submitted to the Shah, handing him the lands under his control. The ruler of the Safavids, in turn, appointed Muhammad Khan Ustajlu governor of Diyarbekir. As the Safavids were defeated in the Battle of Chaldiran in 1514, governor Muhammad Khan Ustajlu too lost his life. As a result of famous historian Idris Bitlisi’s activities to rally Kurdish begs, along with the support of Sunni principalities and tribes, the people of Amid rose in revolt behind Ahmed the Brave (al-Malik Ahmed) – himself a son of Amid – and managed to push the Safavid army out of town.

Upon coming under Ottoman rule, the Diyarbekir Beylerbeylik (Province) was established with Amid as its center, and Bıyıklı Mehmed Pasha appointed as its governor on the 4th of November 1515. With the acquisition of the Fortress of Mardin by the Ottomans in 1517, all forts and important centers in the Diyarbekir region such as Hisn Kayfa/Hasankeyf, Ruha/Urfa and Siirt were effectively gathered under a single administration. According to a cadastral survey conducted in 1518, there were twelve sanjaks under the Diyarbekir Beylerbeylik: Amid, Mardin, Sinjar/Shingal, Berriyecik/Birecik, Ruha, Siverek, Çermik, Ergani, Harput, Arapgir and Kiğı. Additionally, administrative units governed through the yurtluk-ocaklık and hükûmet system (i.e. as dynastic hereditary fiefs) such as Çemişkezek, Atak/Lice, Palu, Eğil, Çapakçur, Sason, Tercil/Hazro, Kulp, Bitlis, Cizre (Jezireh), Genç, Cüngüş and Hisn Kayfa also fell under the Diyarbekir Beylerbeylik.

According to cadastral records the city had four gates and four neighbourhoods named after these (Bab al-Mardin/Mardin Gate, Bab al-Rum/Urfa Gate, Bab al-Jabal/Mountain Gate and Bab al-Ma/Tigris Gate). Non-Muslims were the majority in the most crowded of these neighbourhoods, namely Bab al-Ma. Muslims comprised 54 percent of the city’s total population.

An inseparable part of Diyarbakır in terms of its historical topography, the Hevsel Gardens have been influential in shaping the town’s economy and social structure as well. Its first mention in historical documents appears in records of a siege laid on Amedu (Amedi, Amida) by Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II in the 9th century B.C. Here it is written that upon failing to capture the city, the king had the soldiers guarding its outer gates killed and the gardens outside the walls destroyed.

In the 4th century A.D. Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus made mention of the gardens in his accounts. Yet another historical document is the inscription in the Great Mosque (Ulu Cami). Here Ghiyas al-Din Kaykhusraw II announces that he has abolished the taxes on the Hevsel Gardens along with those on the Mardin, Urfa and Tigris gates. The Hevsel tax was levied on income generated from agricultural activities.

In his “Book of Travels (“Seyahatname”), 17th-century writer Evliya Çelebi mentions the contribution these taxes made to the town’s overall revenues as well as the sheer variety of produce in the gardens. He also noted down the rose gardens in Hevsel, where the townsfolk would spend six months every year enjoying outdoor traditional “fasil” performances, the delightful fragrances rising from the orchards, and the wonderful basil gardens.

(In order to take a glimpse at Diyarbakır from the eyes of travellers through history, check: “History as recorded by travellers”)

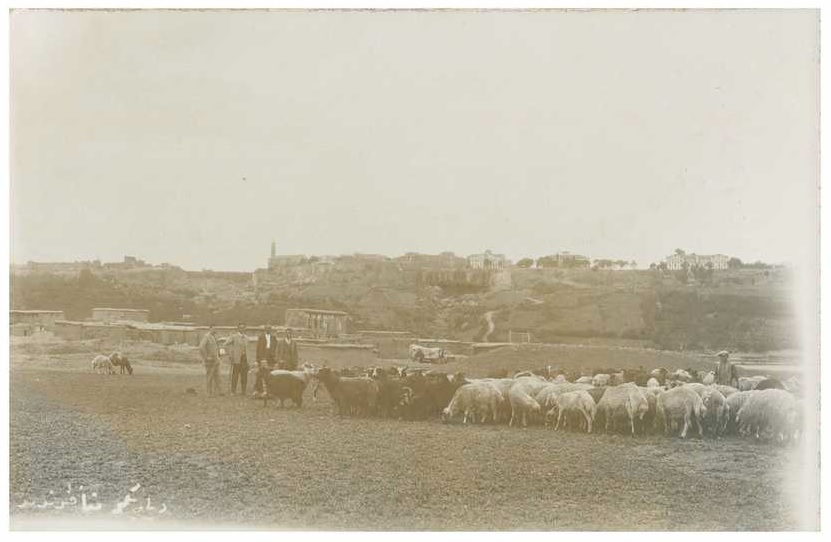

Carsten Niebuhr, a German traveller and mathematician serving the Danish King, found his way to Amid in 1766 and drew up plans of the city during his visit. In his notes Niebuhr mentioned that a great majority of the populace had moved elsewhere due to a famine occurring nine years prior to his arrival, and that there were sixteen thousand – mostly vacant – houses in the city. He recorded the streets as being stone-paved and clean. He also wrote that Armenians, the Assyrian Orthodox (also known as the Yakubi/Yaqubi denomination) and Jews comprised a fourth of the total population. Among other details that caught his attention were the cemetery west of the city walls and the vaults that would hold snow during the summer.

(To look for the city in maps from the Middle Ages onwards, check: “Maps: from Amida to Caramit”)

A site of uninterrupted settlement ever since the early ages, Diyarbakır became home to a great number of different civilizations, cultures, languages and faiths. From records at hand, a cadastral register dated 1540 lists the city center as containing 69 neighbourhoods, 42 of which belonged to Muslims and 27 to non-Muslims. 9262 out of a then total population of 20 thousand were Muslims, while 10,741 were non-Muslims. Though a majority of the Muslim population were Kurds (Kurmanji speakers) and Zazas, there were also Turks – particularly those appointed as administrators, soldiers and officials. The non-Muslim population, on the other hand, was comprised of Armenians, Assyrians, Chaldeans, Nestorians, the Shemsi community, Yazidis and Jews – with a majority of Armenians. The Christian population organized itself in 27 congregations/communities associated with the Small Church, Church of Khidr Ilyas (Elisha/Elijah), Mar-Kozma, Church of the Virgin Mary and the Nestorian Church. Some, based on which community they belonged to, were registered as having come from areas such as Cıska, Atak, Eğil, Hisn Kayfa, Sasun and Mardin.

Of the total population in the entire Diyarbekir province, which numbered 423,270 in the 16th century, on the other hand, 363,375 were Muslim and only 59,895 non-Muslim. One reason behind the higher concentration of non-Muslims in the city center was security concerns, while the other was its bustling commercial life. Raw materials coming in from the south were processed here and then imported back south or north. The city was therefore quite advanced in terms of crafts such as weaving – especially silk weaving, jewellery-making, carpentry, copper-smithing, and leather tanning. With its particular location, Diyarbakır constituted a crossroads, a gathering spot and a production hub where goods and people passed from Damascus and Aleppo (Syria) and Baghdad and Mosul (Iraq) into Tabriz (Iran), Erzurum, Revan/Yerevan (the Fore-Caucasus) and to the Black Sea via Trebizond/Trabzon. This multi-faith and multicultural composition started changing towards the end of the 19th century. Uprisings, massacres and diseases did not leave the demographic makeup untouched, and migration and poverty took a dramatic upward turn.

Traces of this ancient diversity, however, are still visible no matter what in Diyarbakır’s tangible and intangible cultural heritage. A portion of its Christian edifices, in particular, remain standing. The Virgin Mary Assyrian Orthodox Church, St. Giragos (Cyriacus) Armenian Church, Mar Petyum Chaldean Church, the Armenian Catholic and Armenian Protestant Church, the St. Sarkis Armenian Church, the Church of St. George, and the Alipınar Nestorian Church – though in partial ruin or with altered functions – are structures that have somehow stood the test of time and all else.

The city went through rough times in the 18th century due to epidemics. Shopkeepers and traders found themselves unable to send goods to surrounding towns. Country roads fell into the grip of lawlessness and disorder from 1825 to 1843, and caravans would frequently be robbed on the way. Uprisings shook the city from time to time, and certain shops and businesses would sustain damages in the process. Many administrative changes took place in the 19th century. Lastly, in 1869, Diyarbekir was comprised of the sanjaks of Mamuret-ul-Aziz/Elazığ, Siirt and Mardin. In 1879 the Sanjak of Mamuret-ul-Aziz/Elazığ was taken out of Diyarbakır and made a separate province. By the Second Constitutional Era, the Diyarbekir province was split up into four sanjaks – one being the center and the others Siverek, Mardin and Ergani. Diyarbakır was also one of the hotbeds of the Sheikh Said rebellion in 1925.

In the first census taken in 1927, when Diyarbakır’s inhabitants still resided exclusively within the city walls, the population count was recorded as 31,511.

Text: Dr. Yusuf Baluken

Translation: Feride Eralp

BIBLIOGRAPHY

• Beysanoğlu, Ş. (2003) Anıtları ve Kitabeleri ile Diyarbakır Tarihi, Vol. 1-2, Diyarbakır Büyükşehir Belediyesi Yayınları, Ankara.

• Çambel, H. ve Braidwood, R. J. (1980) Güneydoğu Anadolu Tarihöncesi Araştırmaları, İstanbul Üniversitesi Edebiyat Fakültesi Yayınları, İstanbul.

• Gümüş, E. (2015) “Hevsel Bahçeleri’nin Tarihi Süreçte Amid/Diyarbekir Şehri İçin Taşıdığı Önem ve Bu Hususun Vesikalara Yansımaları”, Diyarbakır Kalesi ve Hevsel Bahçeleri Kültürel Peyzajı, (ed.) Nevin Soyukaya, Ege Yayınları, İstanbul: 143-153.

• Ökse, A. T. (2015a) “Amida Höyük Bulguları ve Tarihi Belgeler Işığında Eski Çağda Diyarbakır”, Diyarbakır Kalesi ve Hevsel Bahçeleri Kültürel Peyzajı, (ed.) Nevin Soyukaya, Ege Yayınları, İstanbul: 17-28.

• Ökse, A. T. (2015b) “Diyarbakır Kentinin En Eski Yerleşimi: İçkale’deki Amida Höyük”, Olba 23 (Kilikia Arkeolojisini Araştırma Merkezi Süreli Yayını), Ege Yayınları, İstanbul: 59-110.

• Özdoğan, A. (1999) “Ergani Ovasının Yazılı Olmayan Tarihinden Bir Yaprak: Çayönü”, Diyarbakır: Müze Şehir, (ed.) Şevket Beysanoğlu, M. Sabri Koz ve Emin Nedret Dişli, Yapı Kredi Yayınları, İstanbul: 10-25.

• Özkaya, V., Coşkun, A. ve Soyukaya, N. (2013) Körtik Tepe, Diyarbakır Valiliği Yayınları, Diyarbakır.

• Schachner, A. (2006) “Bırkleyn Mağaraları (Dicle Tüneli) Yüzey Araştırması 2004”, 23. Araştırma Sonuçları Toplantısı, Vol. 1, Kültür Bakanlığı DÖSİM Yayınevi, Ankara: 367-377.

• Soyukaya, N. (2013) “Çayönü Tepesi”, Diyarbakır Ansiklopedisi, Vol. 1, Elvan Yayınları, Ankara: 270-272.

EXHIBITION CREDITS

Text

Dr. Yusuf Baluken

Translation

Murat Bayram, Fethullah Özmen (Kurdish)

Feride Eralp (English)

Design

Fika

Publication date

November 2019