In order to give meaning to the current landscape of the natural environment that created Diyarbakır, it is necessary to look at the transformation the region has undergone due to the policies and choices that have not prioritized nature and, societal events that have changed the flow of life. The freshest traces of this transformation that also directly threatens the rich fauna and flora of the area are to be found in the last few centuries.

In this exhibition, at the outset, environmental historian Zozan Pehlivan creates this specific perspective regarding Diyarbakır’s ecology by establishing historical connections and touching upon the social and political atmosphere. A trip across Diyarbakır’s mountains, highlands, waterfronts and forests over the last few centuries begins with a poem of Ahmed Arif, penned with great depth of wisdom.

Following the historical framework presented by Pehlivan, the topics that independent sections focus on include the natural environment of Diyarbakır and its rich flora and fauna…

They bloom,

Blood red roses

As snow falls,

And Karacadağ mountain sways,

And the highlands sway…

See, my moustache is frozen,

And I feel the chill, too

The dead of winter lingers on and on,

I think of you as springtime,

I think of you as Diyarbekir,

So much it can triumph over

The taste of thinking of you.

These lines from Diyarbakır’s renowned poet Ahmed Arif’s poem titled “Notes from Diyarbekir Castle and the Lullaby for Baby Adiloş” are not only more poetic than thousands of pages of academic text that would describe the geography of Diyarbakır¹ and its ecological diversity, but also quite informative. The different ecological areas he describes and the climatic differences between them serve as all but evidence of the incredible connection he established with the geography of the region.

As Arif reveals in his poem, the season is now spring across the vast plains of Diyarbakır and blood red roses are everywhere. In contrast, higher up across the highlands around Karacadağ, the delirious wind continues blow. Climbing a little further up, there is light snowfall on Karacadağ. The power of the wind and snow has an impact on everyday life in the lower Diyarbakır plain. These are now the final days of a lengthy winter.

Departing from this magnificent poetic narrative by Ahmed Arif, one could describe the physical geography and flora of Diyarbekir and its environs from a historical perspective. Although the focal point of this portrayal is the 19th century, it is necessary, with a Braudelian, long-term historical viewpoint, to delineate the change and transformation the geographical structure of Diyarbekir has undergone, be it with a brief preamble. Such a framework may help guide us in understanding the change that continues from the past to the present day.

¹ Throughout the text, Diyarbakır/Diyarbekir denotes a wider geographical area rather than Diyarbakır city centre. If we were to think on the basis of the Ottoman administrative structure of the 19th century, the geographical area mentioned here corresponds to the vilayet, or administrative division of Diyarbakır. Both the borders and the physical scope of this administrative unit was changed countless times both in the modern and early modern periods. See Yılmazçelik, 1995.

Leaving Egypt to the south aside, Diyarbakır and its environs were one of the empire’s most important grain supply centres in the east, from the year 1516 on, when the area became part of the Ottoman Empire. The vast Diyarbakır plain did not only feed the army on alert against Persia and Russia, the empire’s neighbours to the east. It also provided for army and navy forces in a broad geographical area that extended from Iraq to the Persian Gulf and from there to the Indian Ocean, forming infrastructure for the perpetuity of the empire throughout the early modern period (1400-1800).

Without wheat, rice and other important grains brought from Diyarbekir and its environs, the expansionist imperialist policy of the empire, spreading out towards the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean, would not have been impossible. What rendered this policy operational was these significant raw material sources and at times, the existence of craftspeople.

The province that served as the grain storage of the empire in the east had further significant qualities than supplying wheat: Mining and lumbering.

Copper mined at Ergani Maden was among the leading factors that made the area important for the empire. Raw copper mined here would be sent to Central Anatolian towns like Tokat to be processed and also transported to areas further south, like Iraq and the Persian Gulf. This important raw material source needed by the army and navy forces lost its former significance with the development of the arms industry throughout the 19th century, however, it remained a significant production item in the regional economy.

The environmental impact of continuous copper mining over centuries was enormous. The fuel needed to melt and process copper could only be supplied by using wood from the forests of Diyarbekir and the wider geographical area of Kurdistan.

The destroyed forests of Kurdistan in general and the Diyarbekir province in particular did not only cater for the wood needs of Ergani Maden. Forestry products brought from here also constituted the basic construction material for the mine site. Besides, timber harvested here was also exported to other regions of the empire that had considerable need for forestry products. Especially during the early modern period, timber brought from the Kurdistan heartland supplied a massive part of the requirements of the Ottoman Empire’s shipyards in Iraq and the Persian Gulf. Without the timber produced in Kurdistan, neither the shipbuilding industry at shipyards in Iraq, nor the imperial authority of the empire in the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean would have been possible.

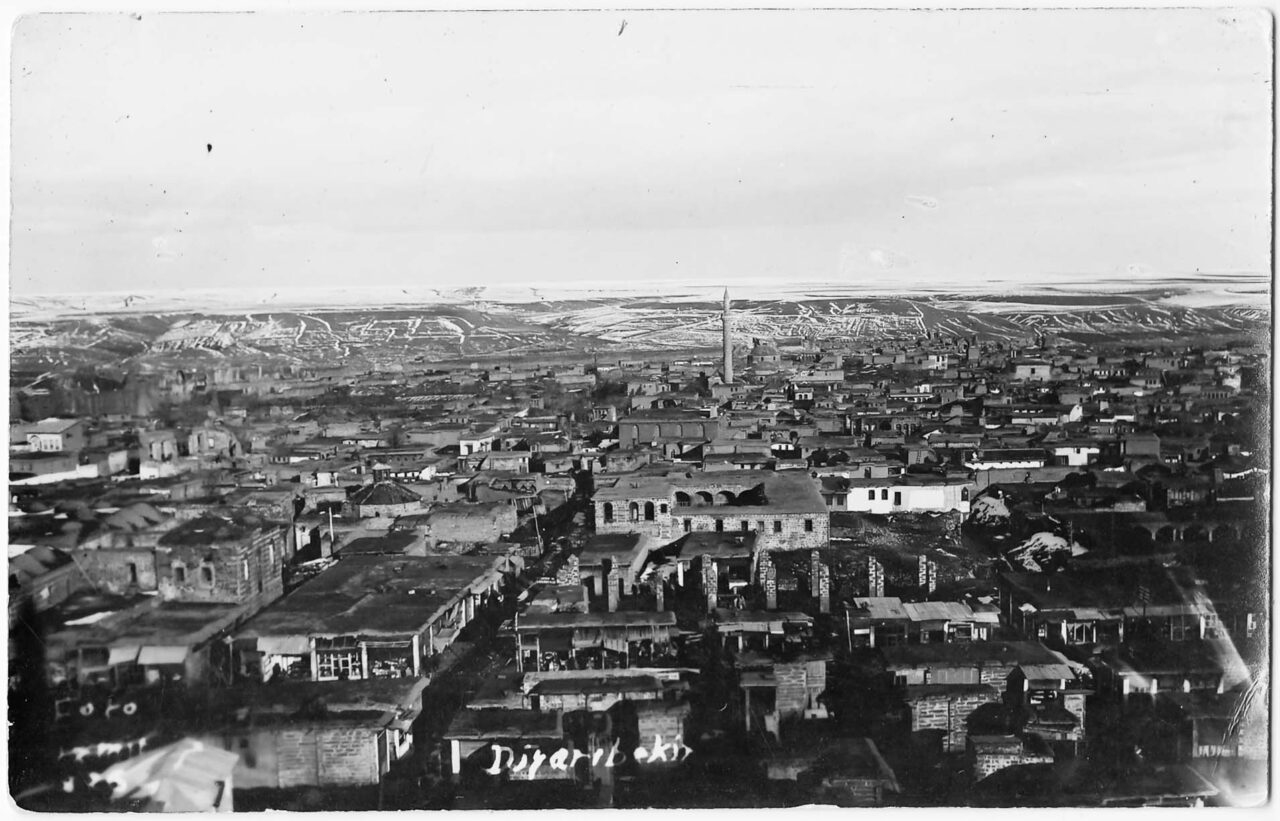

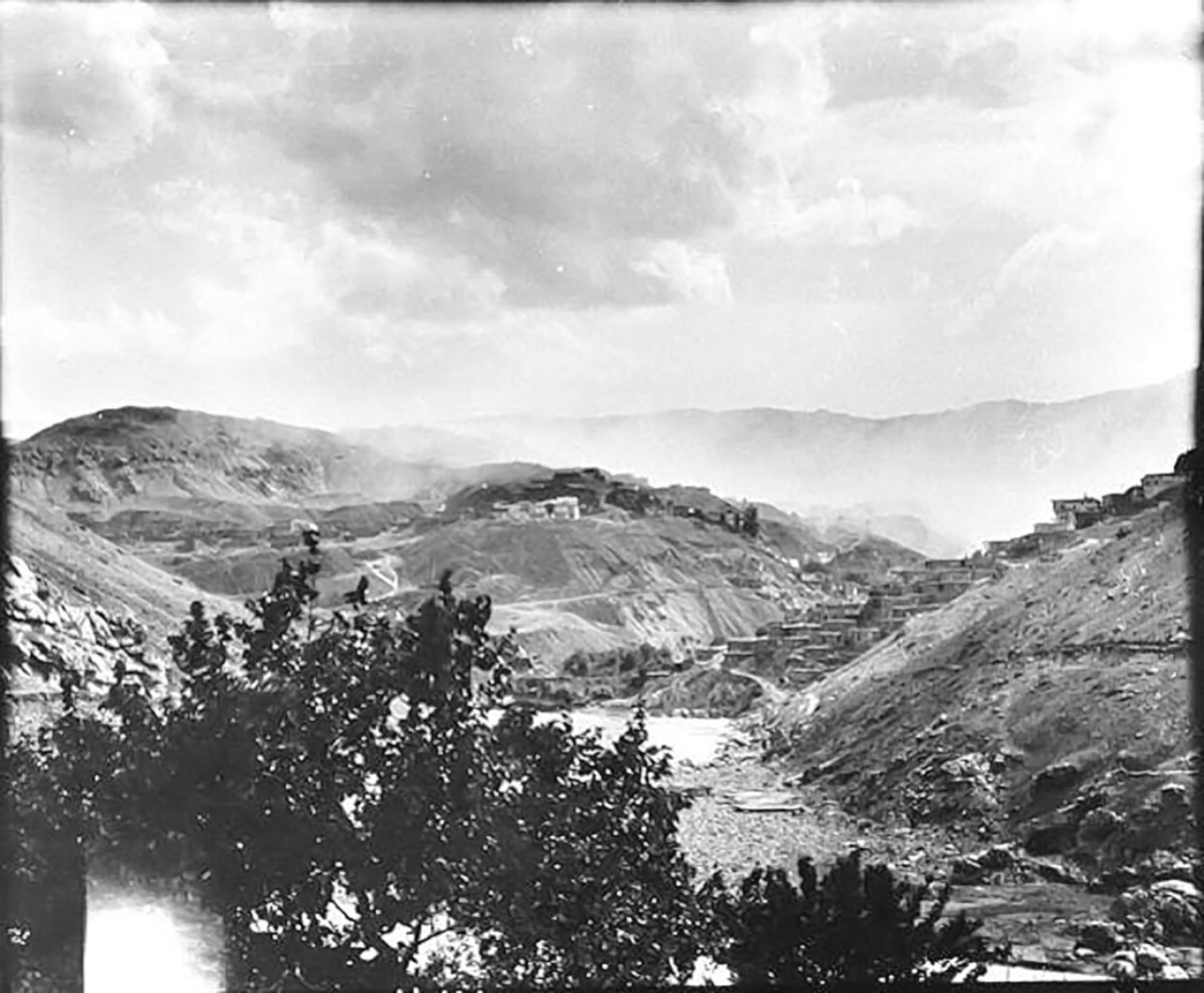

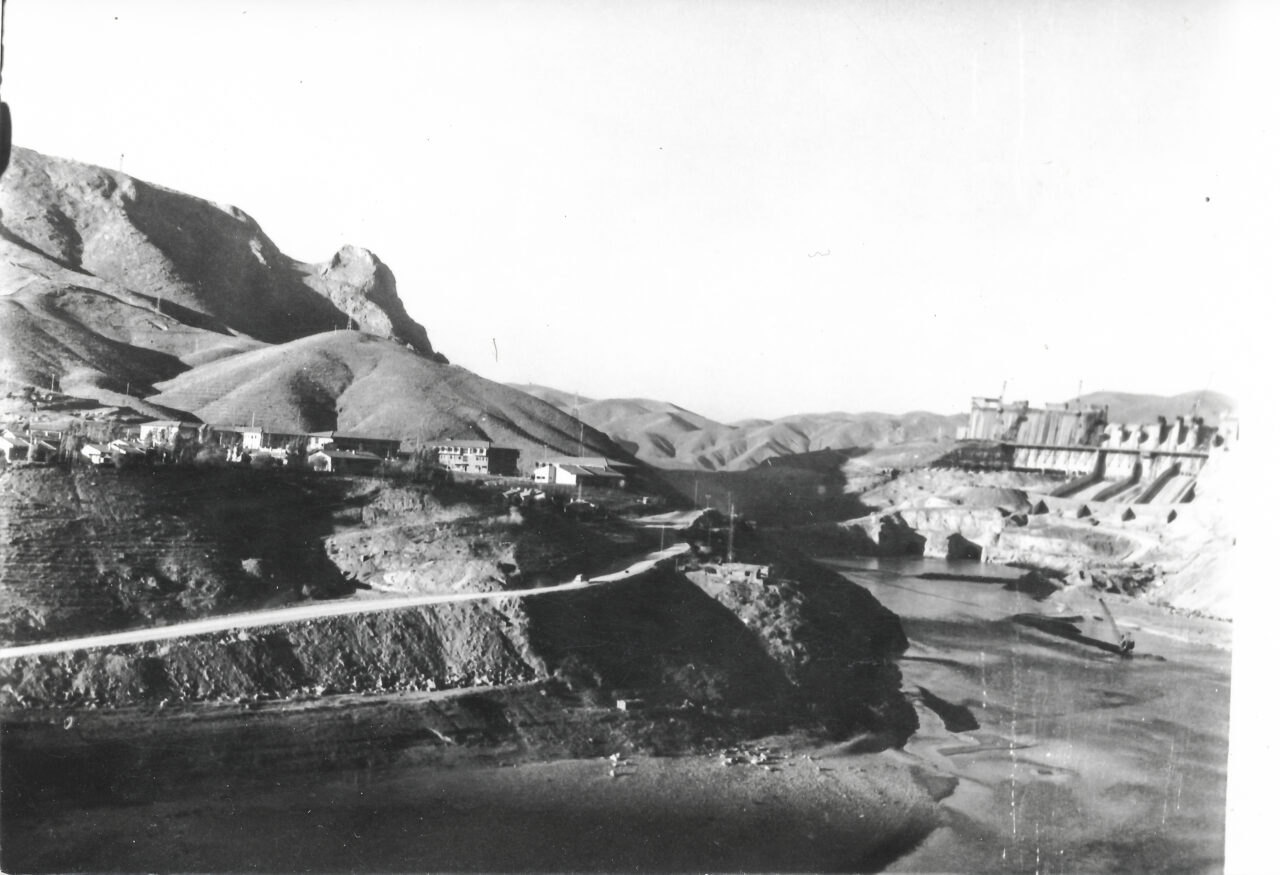

Although significant changes had taken place in the amount of raw material sources procured from the region by the 19th century, the Diyarbekir vilayet remained the most important grain silo of the empire in the east. The appearance of 19th century Diyarbekir and its environs was considerably different compared to the present day. The region had not yet been invaded by dams, constructed on a regular basis from the mid-20th century on.

The outlook of the region was different not only in terms of physical geography but also flora and fauna. In terms of physical geography, Diyarbekir and its environs were home to different types of habitats. The northern, mountainous part of the region formed a western extension of the great Persian Plateau. This area was bordered to its south by the Taurus mountains, undulating plains surrounded by river valleys and colossal high meadows. While some of these meadows were broad and fertile, others were rocky and narrow. Many large and small originate in this mountainous area and feed the two great rivers of the region, Tigris and Euphrates.

In contrast with the northern section, the prominent features of the central and southern sections of the region were the wide plains and meadows extending between the Tigris and Euphrates. This undulating plateau formed the uppermost section of the Mesopotamia plain. Departing from this point, the geography of the region should be described via different ecological regions, in relation to topography, elevation and climate. Concordantly, it is possible to divide the area into three environmental regions.

The first ecological region forming Diyarbekir and its environs comprised the hilly and mountainous lands covering the Diyarbakır Basin with high mountains and deep river valleys. A crescent-like line passing through Hısn–ı Mansur (Adıyaman), Malatya, Harput, Palu, Çapakçur, Muş and Bitlis extended to the north of the vilayet.

In addition to mountains, the major features of this region were deep river valleys and fertile plains. Small and large sources including the Murad River fed into the Euphrates, irrigating the otherwise arid southern plains. Rich freshwater sources allowed for irrigated farming in the region, enabling the cultivation of cotton, tobacco and rice in addition to grains. The plains of Malatya, Harput, Palu and Muş formed the important agricultural lands of the region.

The second ecological region can be described as the Diyarbakır Basin. In contrast to the mountainous north, the elevation of approximately 700 metres was much lower. Located to the south-west of the administrative capital and magnificently depicted by Ahmed Arif, the Karacadağ Volcano was the highest point of this region at 1957 metres.

Apart from the semi-mountainous and hilly terrains around Lice, Kulp, Sason, Beşiri and Siirt, this region was entirely formed of plains. In addition to Tigris and Euphrates, the Batman, Ambar, Sinan and Botan rivers were the main water sources of this central region.

Siverek, Çermik, Ergani, Lice, Silvan (Farqin), Beşiri, Redvan and Garzan were among the leading agricultural areas in this zone.

The third ecological region can be divided into two sections in terms of the presence of water sources, elevation and differences in physical qualities.

Tur Abdin, the entirety of the hilly area to the north of the great Mesopotamia plain between the Tigris River to the east and Karacadağ to the west, formed the first part of this region. Further south, the conditions were even more arid. There were a few streams in addition to the Çağ Çağ River and the Tigris in the lands to the south-east of Viranşehir and Nisibin (Nusaybin). However, these streams were small and thus insufficient in supporting irrigation systems. This meant that fertile terrain suitable for agricultural production remained restricted.

Mardin and Midyat, both overly dependent on precipitation, were among other primary agricultural areas. Thus a series of climatological disasters that took place in the second (1844-1846) and final (1879-1895) quarters of the 19th century, threw social and economic life here into complete disarray. These disasters also caused mass animal deaths.

From the late 1870s on, life in rural areas faced interruptions due to drought, resulting, for instance, in the abandonment of hundreds of villages around Mardin. Local people sought to balance out the arid conditions, or rather cope with the difficulty by building water wells and cisterns, to be used in irrigation as well. It was thanks to these irrigation wells that commercial agricultural products could be produced in the region, with tobacco first and foremost among them.

Geographical differences within these three ecological regions, rendered some ecological areas more vulnerable to changing rainfall patterns. In the mountainous northeast, around Malatya, Harput, Çapakçur, Kulp and Lice, winters tended to be extremely cold. The winter snow allowed highly nutritious grass and other plants to cover the plains throughout, feeding hundreds of thousands of small and large cattle in the summer months. In the central plateau surrounding Diyarbakır province, summers were hot and winters cold, even if the precipitation was less. Further south, the climate resembled desert conditions; summers were hot. In these areas, in the months of July and August the temperature rose above 40 degrees Celsius at times.

The use of land and settlement also varied in these regions because of differences in elevation and precipitation. Thanks to rich water resources that created fertile land and enabled irrigation, the Diyarbakır Basin became the area of most intense agriculture in the region. Watered by various tributaries of the Euphrates, the Malatya and Harput Plain had been cultivated less compared to the central region.

The southern parts of Diyarbekir were mostly covered with orchards and pastures. Typically low and stunted and occasionally as short shrubs, oak was the most common tree. In addition to the oak tree, poplar, the most useful tree for the construction industry, grew particularly on land with high humidity around villages. There were good pastures in the meadows extending between the mountains to the northeast of Diyarbekir province. Plateaus along the skirts of Karacadağ formed further significant grazing areas in the central part of the region. Other than this, there were highly fertile pastures in Mardin and its south and especially the flatlands of Northern Mesopotamia.

This entire geographical zone and flora began to undergo major change in the 20th century. This was a transformation carried out by human hand. Control mechanisms that expanded along with the nation-state and the centrally planned and rurally implemented systematic policies of the technocratic worldview increasingly led to massive environmental destruction.

Today, the sequence of dams that pervades the entire area from end to end does not only bury deep river valleys, towns and ancient cities of tens of millennia under water. Dams also submerged the endemic flora and wild life of this region. Besides, gigantic dam lakes also triggered changes to the region’s arid and semi-arid climate.

The Diyarbekir described by Ahmed Arif remains only in lines of poetry and archive documents. Today there is a different Diyarbakır, a different environment, a different flora and a different climate.

What tomorrow brings will therefore be determined by the destruction and pillaging taking place today.

Text: Assistant Professor Zozan Pehlivan, Environmental Historian

Translation: Nazım Dikbaş

Cover photograph: Mehmet Masum Süer

BIBLIOGRAPHY

• Ateş, S. (2013) The Ottoman-Iranian Borderlands: Making a Boundary, 1843-1914, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

• Aydıner, M. (2008) “XVIII. Yüzyılın İkinci Yarısında Diyarbakır’da Büyük Kıtlık [Diyarbakır’s Great Famine in the Second Half of the XVIII. Century]”, Osmanlı’dan Cumhuriyet’e Diyarbakır, Vol. 1, (ed.) Bahaeddin Yediyıldız and Kerstin Tomenendal, Türk Kültürü’nü Araştırma Enstitüsü, Ankara: 275-86.

• Beysanoğlu, Ş. (1962) Diyarbakır Coğrafyası [The Geography of Diyarbakır], Şehir Matbaası, Istanbul.

• Brant, J. (1840) “Notes of a Journey Through a Part of Kurdistán, in the Summer of 1838”, Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London, 10: 341-434.

• van Bruinessen, M. and Boeschoten, H. (ed.), (1988) Evliya Çelebi in Diyarbekir: The Relevant Section of The Seyahatname, E.J. Brill, Leiden.

• Dickson, B. (1910) “Journeys in Kurdistan”, The Geographical Journal, 35(4): 357-78.

• Erler, M. Y. (2010) Osmanlı Devletin’de Kuraklık ve Kıtlık Olayları, 1800-1880 [Drought and Famine in the Ottoman State, 1800-1880], Libra, Istanbul.

• Ertem, Ö. (2012) Eating the Last Seed: Famine, Empire, Survival and Order in Ottoman Anatolia in the Late 19th Century, PhD Thesis, European University Institute.

• Husain, H. F. (2020) Rivers of the Sultan: The Tigris and Euphrates in the Ottoman Empire, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

• Kasaba, R. (2009) A Moveable Empire: Ottoman Nomads, Migrants, and Refugees, University of Washington Press, Seattle.

• Ertaş, K. (2015) Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’nda Diyarbakır Ermenileri [Diyarbakır Armenians in the Ottoman Empire], Rağbet Yayınları, Istanbul.

• Maunsell, F. R. (1896) “Eastern Turkey in Asia and Armenia”, Scottish Geographical Magazine, 12(5): 225-41.

• Maunsell, F. R. (1894) “Kurdistan”, The Geographical Journal, 3(2): 81-92.

• Pehlivan, Z. (2020) “El Niño and the Nomads: Global Climate, Local Environment, and the Crisis of the Pastoralism in Late Ottoman Kurdistan”, Journal of Economic and Social History of the Orient, 63(3): 316-356.

• Pehlivan, Z. (2019) “Küresel Perspektifle Bölgesel Olana Bakmak: Osmanlı Kürdistanı’nın Çevre Tarihi [Seeing Regional Events from A Global Perspective: Environmental History of Ottoman Kurdistan]”, Toplumsal Tarih, 312: 38-43.

• Pehlivan, Z. (2016) Beyond “the Desert and the Sown”: Peasants, Pastoralists, and Climate Crises in Ottoman Diyarbekir, 1840-1890, Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, Queen’s University.

• Pehlivan, Z. (2016) “Abandoned Villages in Diyarbekir Province at the end of the ‘Little Ice Age’”, The Ottoman East: Trans-regionalism, Fluid Identities and Local Politics in the 19th and 20th Centuries, (ed.) Yaşar Tolga Cora, Dzovinar Derderian and Ali Sipahi, I. B. Tauris, New York and Londra: 223-246.

• Salzmann, A. (2004) Tocqueville in the Ottoman Empire: Rival Paths to Modern State, Brill, Leiden.

• Saraçoğlu, H. (1989) Doğu Anadolu Bölgesi [The Eastern Anatolian Region], Milli Eğitim Bakanlığı [Ministry of National Education], Istanbul.

• Sözer, A. N. (1984) “Güneydoğu Anadolu’nun Doğal Çevre Şartlarına Coğrafi Bir Bakış [A Geographical View of the Natural Environmental Conditions of Southeastern Anatolia]”, Ege Coğrafya Dergisi, 2: 8-30.

• Tabak, F. (1988) “Local Merchants in Peripheral Areas of the Empire: The Fertile Crescent during the Long Nineteenth Century”, Review, 11(2): 179-214.

• Yılmazçelik, İ. (1995) Yüzyılın İlk Yarısında Diyarbakır, 1790-1840: Fizikî, İdarî ve Sosyo-Ekonomik Yapı [Diyarbakır in the First Half of the XIX. Century, 1790-1840: Physical, Administrative and Socio-Economic Structure], Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi, Ankara.

EXHIBITION CREDITS

Contributing authors

Prof. Dr. A. Selçuk Ertekin, Prof. Dr. Sabri Karadoğan, Asst. Prof. Zozan Pehlivan, Prof. Dr. Erhan Ünlü, Zeki Fırat Yıldırım

Exhibition editor

Pınar Öğünç

Translation

Berivan Karatorak (Kurdish)

Nazım Dikbaş (English)

Proofreading

Eren Ünal (Turkish and English)

Abdulsıttar Özmen (Kurdish)

Design

Fika

Publication date

April 2022