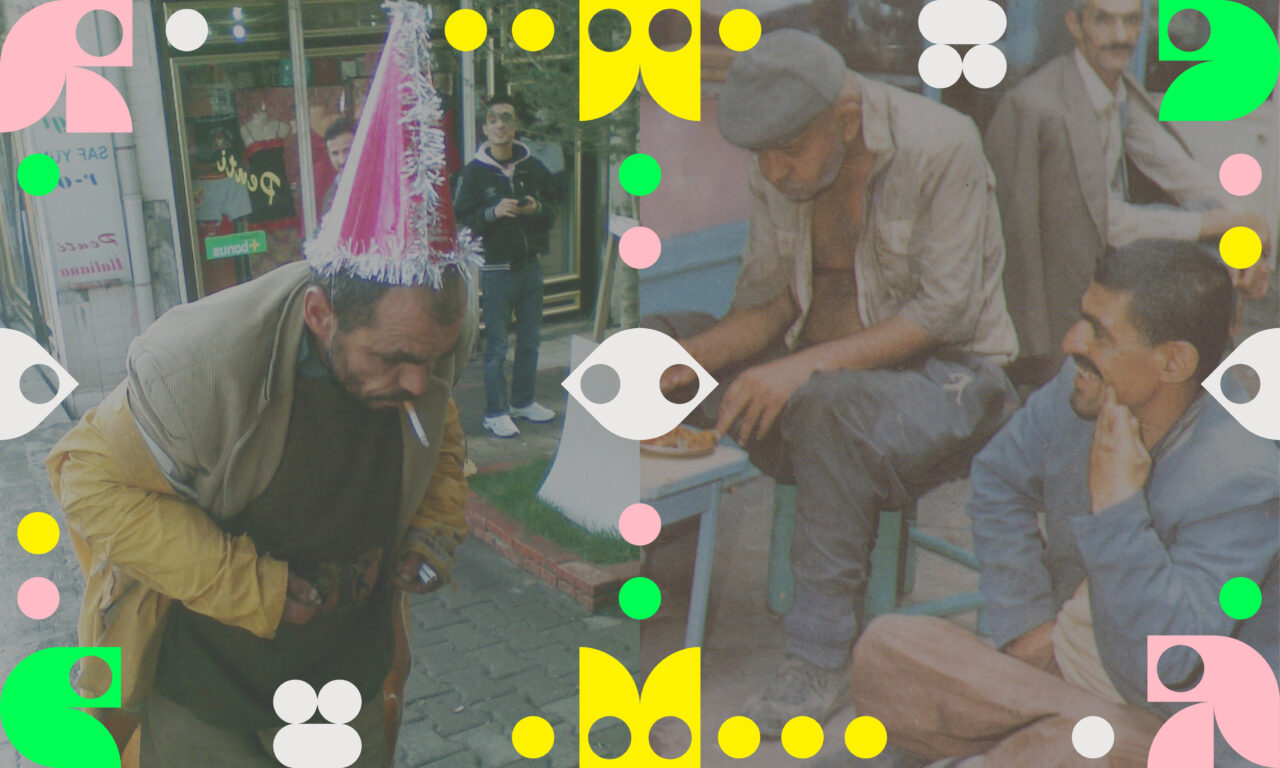

Qırıxs (urban toughs), fools, those who lost their minds and found the light, turned from fool to sage, crazy to “saintly”… Though no book of history mentions their name, they are an inextricable part of Diyarbakır’s urban identity, both with the reasons that brought them into being and the mark they left behind.

Writer Şeyhmus Közgün begins with an account of the qırıxs, who are unlike “tough guys” in the sense we might first imagine, and the qırıx culture they have formed, moving on to provide a collection of portraits of the city’s unforgettable “mad people” – or rather “patron saints” who have been touched by the Divine.

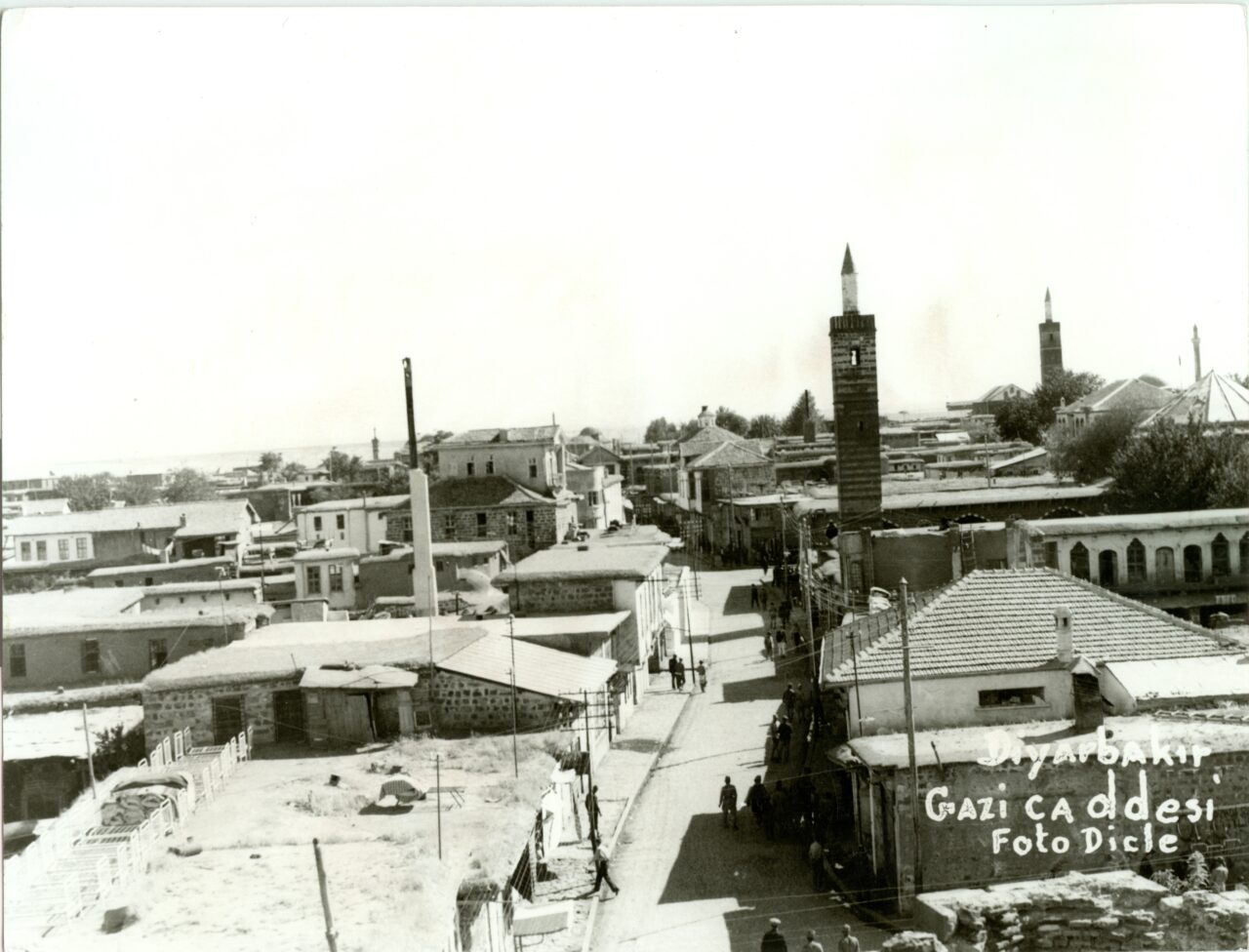

When speaking of Diyarbakır’s neighborhood culture, streets and street corners are first to come to mind. For “qırıxs”, streets and street corners connote territories with boundary lines drawn. Who are these qırıxs? Some call them “keko” (older brother), some call them “gedê bajêr” (boys of the town).

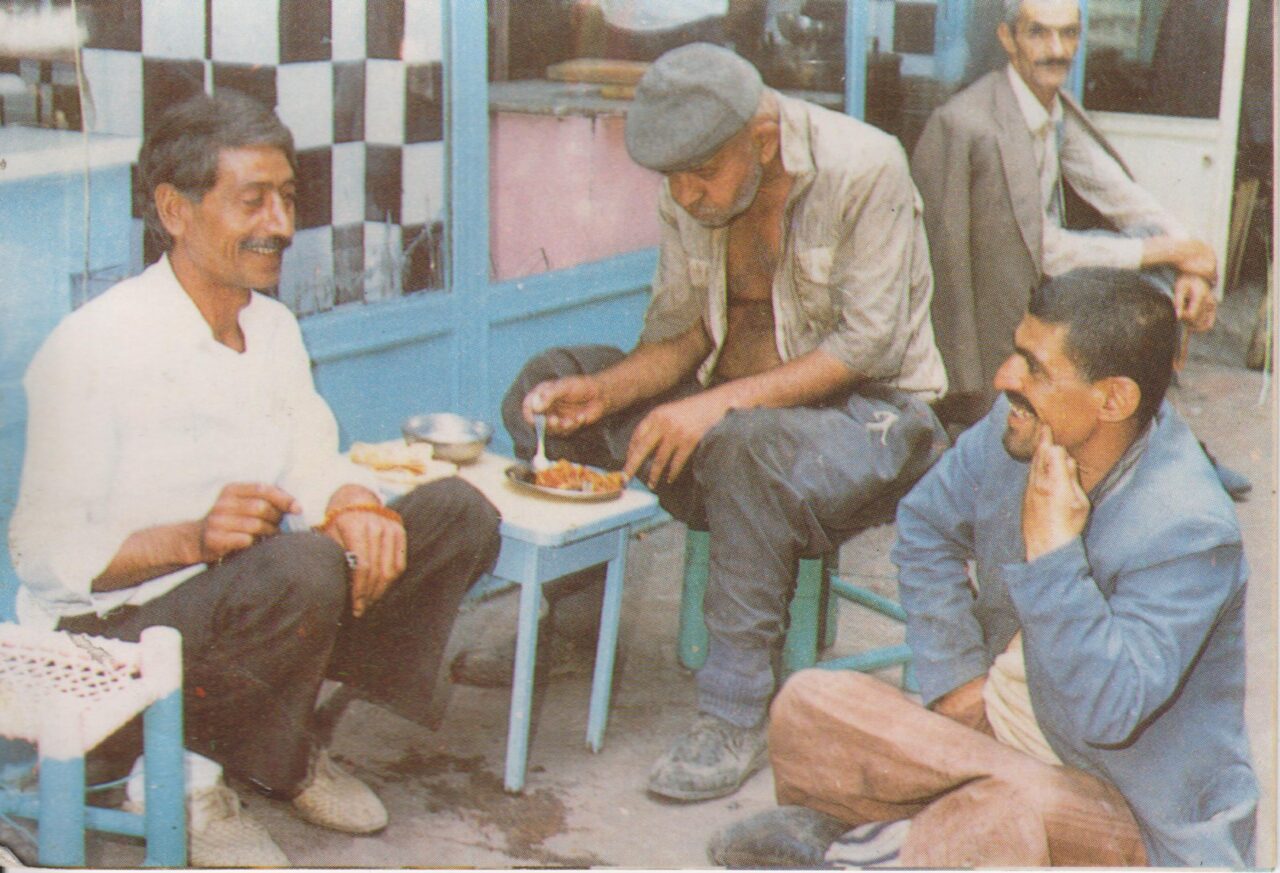

In the Diyarbakır of old, those brave of heart, who stood by the weak and the poor, and commanded authority among citizens were held in a different regard. These “tough guys” who feared no one, and welcomed all kinds of trouble when necessary with a certain kind of grace were respected and cherished by inhabitants of the town. Their “code” was to prowl the streets and keep gentle watch, without wronging anyone and always making sure to behave respectfully towards women. Their speech, their gait, even the way they held themselves was somehow different. They were rebels by disposition, checking out the world around them with an air of insolence that read “What’s the problem?”.

Kabadayı (strongmen), külhanbeyi (rowdies), qırıx (toughs)… Though all of these sound akin, qırıxs and the culture formed around them can only be understood by taking certain nuances into account. What set them apart from urban bullies in the eyes of the people of Diyarbakır was first and foremost the fact that they were cognizant of the historical, social and cultural atmosphere they were part of, and had developed a certain sensibility for issues from migration to political pressure, economic difficulty to armed conflict. In the sociopolitical setting created by all of these conditions qırıxs emerged as protective figures, at times assuring safety, at times meting out justice.

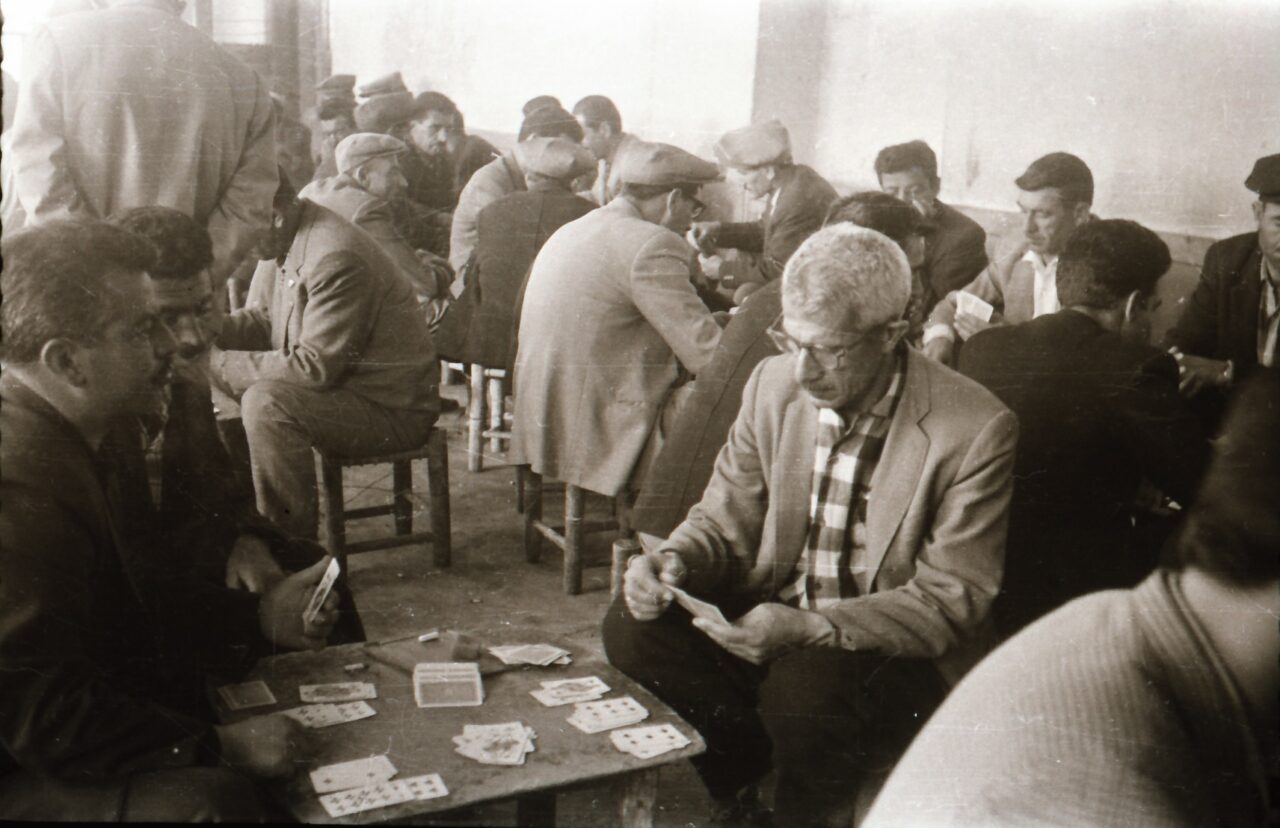

A qırıx could do the rounds of the neighborhood like a guard as everyone slept, and take the seat of honor at a wedding. They sometimes mediate problems, other times they exact their own “retribution”. It is due to this that a qırıx will most necessarily cross paths with the justice system for a variety of reasons.

Nicknames are particular to the person, for they have either been earned by strength of arm or ascribed by someone for a certain reason. Cenneh (Club), Sator (Cleaver), Bozo (Blondie), Kınê (Shorty), Aluce (Plum), Eqrep (Scorpion)… Nicknames matter.

Selax Sait

One of these important characters, Selax¹ Sait was born in Diyarbakır in the 1880s. Before becoming a renowned strongman, he actually worked in an abattoir (slaughterhouse).

He was well liked and respected by the populace, for when there was an incident causing tension he would intervene and prevent fights from escalating. He looked out for the poor. In fact, Mustafa Gazi, who worked most extensively on the topic of the qırıxs, mentions in his book that Selax Sait wrote letters to the rich requesting gold to distribute to the poor, describing him as the nightmare of the rich.

Selax Sait was in trouble both with others and with the system. Gazi writes that the strongman, a long-time fugitive, was eventually captured by the authorities and hanged to death from the Ten Eyed Bridge. Before he died, he left his friends a poem.

I set up tent on the plains

A thorn I was to their gains

Friends, and now I must go

Diyarbekir, I leave to you.

¹ Selax: Butcher of animals.

Yunus the Jew

Writer Mıgırdiç Margosyan distinguishes between strongmen – or urban toughs. There are those extortionists who plague simple folk who are just trying to stay afloat, and then there are those who stand by these people and stand up to the strongmen who harass them. According to Margosyan, Yunus the Jew is of the second kind. His charm doesn’t come from his clothes, his handsome looks or combat skills. What matters is his courage and who he chooses to stand by.

With the founding of the State of Israel in 1948, the Jewish Quarter in Diyarbakır started being vacated. Houses were sold dirt cheap, and preparations for the long journey were afoot. In recounting those days he witnessed, Margosyan mentions two exceptions. One of those unable to join the families who were leaving was Yunus the Jew. In fact, his killing in an ambush around that time is said to have expedited the Jewish exodus from the city. Another exception that couldn’t leave the city in this wave of migration is Ferho, whose turn will come in the section on the “mad folk”.

Kurdo Meheme

Kurdo Meheme (Kurdish Mehmet), his real name Mehmet Altın, was born in the village of Hacidel under Diyarbakır’s central district in the mid-1940s. He often got around in a suit and shirt, and wore his salwar pants only from time to time. Nobody could best him in a fight – many had happened to prove this. Yet in spite of this, he was a strongman whose “gentlemanliness” was recognized by all. His stance against bullies and tyrants was clear.

Kurdo Meheme spent a lot of time in different prisons across Turkey. He was also known for his prison breaks. Since this “violent criminal”, as noted in his file, kept up his strongman’s ways behind bars just as he did outside, rumor has it that prison administrations prayed not to have him on their hands.

Cenneh Qado

Cenneh¹ Qado was born in 1938, in Arbedaş, in Diyarbakır’s neighborhood of Saraykapı. He took on this nickname for his particular skill in using the “cenneh” (club) during a fight.

Qado always wore a suit and silk shirt and mostly spoke in Kurdish. As he was known for his grit and fearlessness, people respected him and were slightly intimidated by him. It was said that no robberies, mugging or harassment happened where Cenneh Qado lived. He was famed for taking everyone under his wing and for fighting off those who upset the neighborhood’s peace. He was rumored to be kind enough to beat up a man and then have him treated.

¹ Cenneh: A club used for fighting.

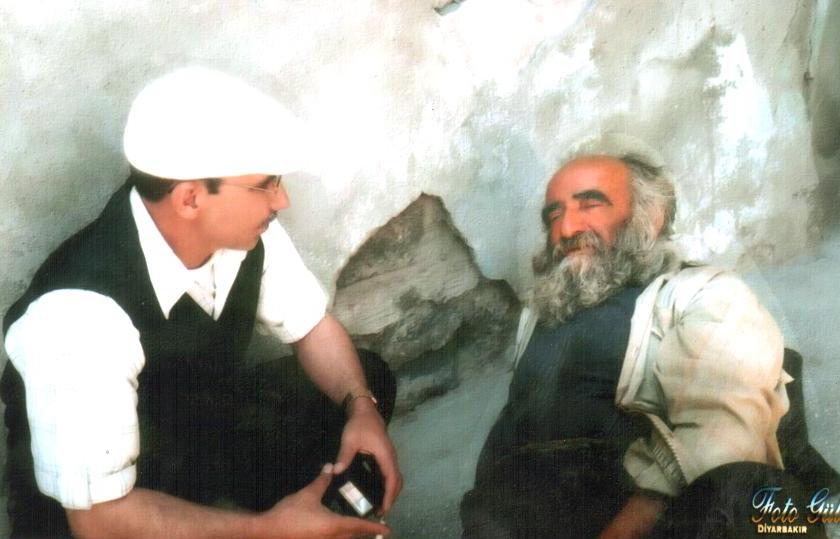

For the people of Diyarbakır who retained their neighborhood culture and wished to preserve humanistic values, the “mad”, “crazies”, “fools” or “eccentrics” of the city have always had a special place. Having “gone mad”, lost one’s mental faculties for one reason or another did not call for being isolated from society – quite on the contrary, these people were treated with particular care. Mad people harmlessly wandering the city streets weren’t shunned and ignored; instead, the community kept in touch with them, looked out for their needs such as food, water, shelter and clothing. Though their behavior often deviated from what was regarded as the “norm”, they weren’t ostracized, but rather reprimanded if necessary. This is mostly still the case, even today.

In fact, some of these “mad” are seen as having unlocked the mysteries of creation. These are considered “sages” or “patron saints.” Their words are considered to wield the power of miracle, and their counsel is taken seriously, particularly on certain subjects. Some believe that these patron saints ward off evil with their eyes, others that they bring abundance to the poor. There are those who believe that seeing one of these saintly fools in a dream will deliver them from their troubles. Doing good to someone considered a saint, receiving their blessings is an important matter.

Alişan

Alişan, one of the most famous of these figures, was born in Derik in 1953. In the winter, he wore a long dress, long women’s underpants, a sweater, jacket, rubber shoes or boots. In the summer, he simply went around in a one-piece dress. Bus drivers didn’t charge him when he took the bus and dropped him off wherever he wanted. He was one of those considered a miracle-worker by the people of Diyarbakır. Some said they saw him at the Kaaba, others claimed to have spoken to him in a dream. It was important to treat him with affection and respect. There were other “crazies” in his family, who were also well known to the people of the city.

While wandering around the courtyards of mosques, Alişan would look at coffins placed on the rest. He would cry for some of the dead, and get angry at others, even spitting on some. People still talk about the massive crowd that turned out to bid him farewell when he, himself, died. His gravestone reads, “The Fool, the Saint of our Diyarbakır” (“Diyarbakırımızın Delisi, Diyarbakırımızın Velisi”) and his name still often comes up in daily conversation. Along with true events that actually did happen to him, it is also a fact that wildly exaggerated stories are spun in his name.

Çolo Meheme

Çolo Meheme of Diyarbakır was born in the mid-1920s. He did have a family, but when he grew bored of them he would let himself loose on the streets of the city. He used to say he communed with the djinn and left his home because of them.

Çolo Meheme had a unique sense of fashion. He could wear a turtleneck sweater with a tie on top even on a hot summer day. He would be happy with people who showed him affection and respect. When kids would sometimes tease him and get on his nerves he would lash out in anger, but he was mostly known as a well-meaning, good-humored soul. In fact, he would bring merriment wherever he went with his cheerful character. Politics was an important topic for him. He sometimes talked like a politician, and sometimes like a close relation of a famous politician. Ecevit was one of his favorites. He was also quite a pious man.

Çolo Meheme put up a long fight against the disease that started with a single boil and spread across his entire body. After becoming bedridden for about three or four months he passed away in the year 1999 according to some and 2000 according to others.

Mehemed of Kulp

Mehemed of Kulp (Sofî Mehemede Kanikî) was born in the village of Kanik (Kanika, İnkaya) in Diyarbakır’s Kulp district. He was a burly, strong and friendly person. He always wore a salwar and never took off his long coat, no matter the season. He carried his long stick like a scepter, and banged it once on the doors and shutters of shops to salute shopkeepers in his own way.

He was seen as a lucky charm, a miracle-worker, and cherished as such. His conversations were a source of enjoyment since he often spoke Kurdish and had a humorous tone. If he had fallen out with someone, he would never forget what had been done to him until amends were made. He had no care for status or money, so he said whatever popped into his mind to anyone and everyone without restraint.

Mad Ferho

The home of Mad Ferho (Ferhe) of Diyarbakır’s Jewish community was in Hançepek. While most Jewish families –their number already dwindling since the start of the century– moved to Israel after 1948, she had stayed for a reason nobody knew. No amount of coaxing, nothing anyone could say had convinced her. She simply did not want to leave Diyarbakır.

Ferho was a delicate woman, without harm to anyone. In her skinny state, she would wander the narrow streets (küçe) of the city all day, bursting out in laughter from time to time, reciting rhymes only she herself could understand. When she was left as probably the only Jew in the city, she also fashioned herself a new name: Selma. Margosyan writes about seeing Ferho on his way to the former Jewish Quarter (now the ‘Korean Quarter’), having started fortune-telling in her new life as Selma Hanım, again wandering the streets, homes, hamams of the city, but this time as a fortune-teller.

Mad Ayno

Mad Ayno (Eyno) of Arab origin was born in Urfa in 1910. She was known and cherished in Diyarbakır. But nobody knew when and how exactly she had come to the city.

Ayno would walk towards her destination unknown to anyone but her, oblivious to the world around her, no matter whether the streets were calm or crowded. It was known that prior to losing her mental health she was married and had a child, but that when she “went mad” her husband asked for a divorce. Losing her home along with her family, Ayno lived on the streets. Her basic needs were covered for years by people looking out for her. At one point she returned to Urfa and died in her city of birth.

Mad Selim

Mad Selim was born in a village in Diyarbakır’s Çınar district in the 1920s. Behind his “insanity” was a love story from his early youth. When he attempted to elope with his uncle’s daughter, whom he was in love with, just as she was about to be wedded to someone else, he was severely beaten resulting in serious head trauma. This was how he came to leave behind his well-to-do family and took to roaming the streets of the city. Over the years, he climbed further up the ladder of “madness”.

Walking around in nothing but a tattered salwar and thin sweater even in ice cold weather, Selim’s reckless abandon, his endurance against the cold was a detail that those who saw him once never forgot. Sometimes he would sit on a rock and spend hours there. His needs such as food and water were met by charitable townsfolk. He never accepted alms. Behind his matted hair and long, unkempt beard his face was bleary yet proud. It was said that his gaze had a strange kind of force field.

Mad Yaşo

Mad Yaşo was born in Diyarbakır in the 1970s. He is said to have lost his mind because of something bad that befell him, but the nature of this is unknown. He would wander the streets in messy clothing taking long jumpy strides.

His relationship with stray dogs in particular inspired awe in the people of Diyarbakır. He was in the habit of traveling with not one dog but a small pack of dogs, which were instantly tame around him. He also took care of chicks, and some saw him share his own scanty meals with these birds. He would only get angry when teased and provoked by people, and he would throw stones he found at them. Since Deli Yaşo’s main haunt during his lifetime was the city center, he had many a friend who cherished and protected him.

Text: Şeyhmus Közgün

Translation: Feride Eralp

BIBLIOGRAPHY

• Gazi, M. (2013) Diyarbakır Kabadayıları Delileri ve Pışo Meheme [Pışo Meheme and the Strongmen and Madmen of Diyarbakır], Lîs Yayınevi.

• Közgün, Ş. (2007) Sisler Korkular [Fog and Fear], Lîs Yayınevi.

• Margosyan M. (2018) Fıllaname [Book of Non-Muslims], Aras Yayıncılık.

A long interview on the content included here was conducted with Abdulkadir Ayus in August 2022, while Ahmet Can, Ramazan Pekyaman, Mehmet İrem, Selahattin Çiçek, and Hamit Cansever contributed to the main framework of this section.

TEACHING, DOCUMENTING