Diyarbakır’s history, when read via production and trade, presents an abundance of materials worthy of its past. The city’s geographical structure and the diversity of climate it creates, meant that there was always a broad spectrum of products. Diyarbakır stands at a crossroads of trade routes in the region, and once it became part of the Ottoman Empire, it also served as a customs gate, thus further increasing the significance of the city.

To extend this historical debate to the present day means that we must discuss not only wars, regional and global change and famine, but also land reform that failed to materialize, policies that condemned the region to economic underdevelopment and the grave outcome of the combination of neoliberalism with such policies. Historian Uğur Bayraktar laid out the framework for Diyarbakır’s Memory. We will then take a closer look via the history of wheat, silk, copper, grape, animal husbandry and jewellery.

![Diyarbakır reinforced its influential position in production and commerce especially after the 16th century, while its historical city walls were also a point of passage. The photograph shows goods being taken off kelek [transport rafts] on the Tigris River, taken past Keçi Burcu [Goat’s Tower] and into the city through Mardinkapı [Mardin Gate].](https://diyarbakirhafizasi.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/1_uretim-1280x765.jpg)

Diyarbekir became part of the Ottoman Empire during its wars with the Safavid Empire in the 16th century, and from that point on, acquired an active role in production and trade. Its location at the border of the empire, in addition to its geographical position reinforced this role. The Diyarbekir eyalet, or administrative division, included a broad mass of land that encompassed the present-day cities of Batman, Elazığ, Mardin, Siirt, Şanlıurfa and Şırnak, and formed the northern part of Kurdistan; while the Tigris River, also known as the Nile of Diyarbekir, divided this expansive region into four parts:

• The central region, rich in basalt rock,

• The northern region, extending from the west to the east, forming a part of the Aladağlar mountain range,

• The southern region, flat and easily accessible apart from Karacadağ and Tur Abdin,

• The eastern region, where the Tigris River draws a geographical line between southern Diyarbekir and central Kurdistan.

In the same way that the Tigris River divides northern and central Kurdistan, the volcanic mass of Karacadağ also divides the plateau into two basins, the one to the east of the Tigris, and the one to the west of the Euphrates. These geographical circumstances lead to varying climatic conditions, however, it is mostly the continental climate that dominates the Diyarbekir area. Traveler James Brant, who visited Kulp, a town to the northeast of Diyarbekir, in the 1830s, observed that the scrubby oak trees covering the low mountains abruptly disappeared and maquis shrubland and cotton fields took over the landscape. Such changes in climate have always been an element that have enriched agricultural production in this broad geographical zone.

![From the 15th century on, Diyarbakır was a stop on the Silk Road, an important commercial route across a broad mass of land. This photograph, taken in the 1920s, is from the historical Zahire Pazarı [Grain Market] in Sur.](https://diyarbakirhafizasi.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/3_uretim-1280x825.jpg)

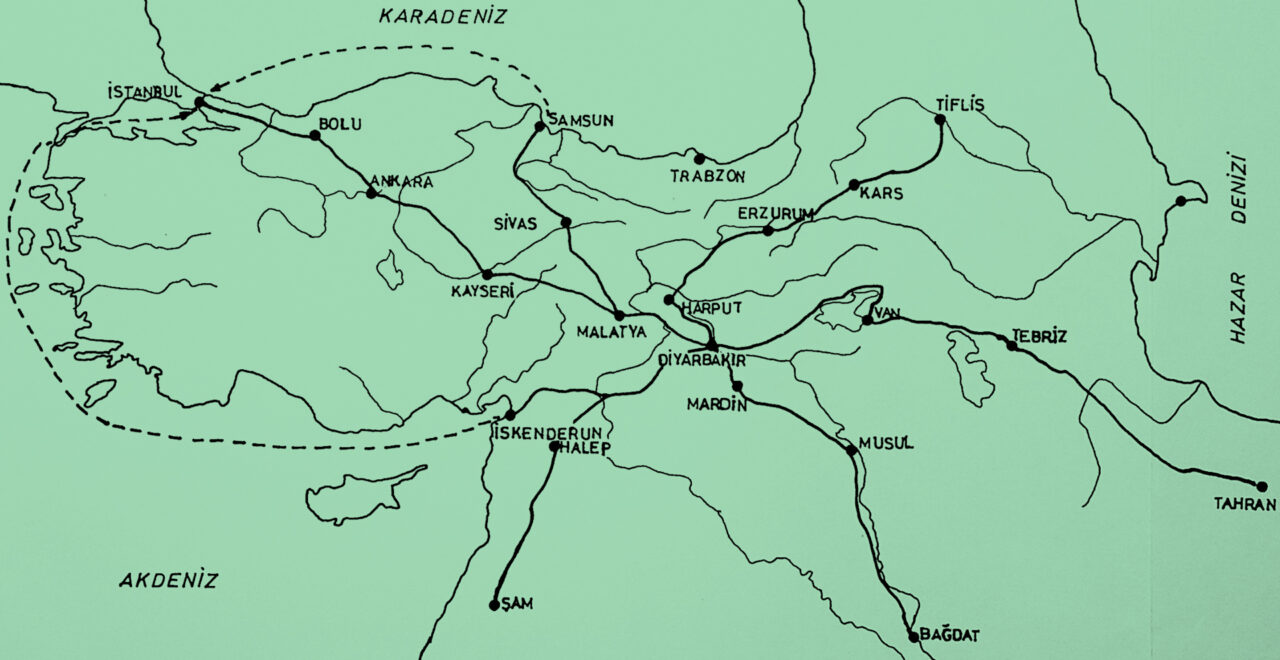

In addition to its rich diversity in terms of geographical features, Diyarbekir was also always important as a crossroads of great trade routes. The city played a key role on the passage known as the Silk Road in the 15th and 16th centuries, especially along the section of it that began in Tabriz, passed through Van, Bitlis and Diyarbekir, reaching Aleppo. Besides, the city was also on the return route of many Christians who completed their pilgrimage to the holy sites in Palestine.

When, from the 17th century on, the silk trade route moved away from Aleppo, first towards Bursa and then İzmir, Diyarbakır lost, to a great extent, its role in long distance trade. Factors other than the transformations the Silk Road underwent also played a role in this. For instance, in 1577, sending 10 thousand kile¹ of wheat from Diyarbekir to Van cost more than the worth of the wheat. Nevertheless, throughout the early modern period, Diyarbekir, just like Aleppo, remained an important stop for tradespeople travelling in the direction of Samsun, Baghdad and Erzurum on trade routes, despite high costs of long distance conveyance. The emergence of new trade routes meant that the good old days faded away, however, in the first quarter of the 19th century, Diyarbekir still had not lost its significance on the old trade routes. The quite diverse product spectrum in records we have from the period is a sign of this, ranging from bowls from Aleppo, çit (hand-painted cloth) from Tokat, kutni (cotton fabric) from Damascus, bowls from Europe, shawls from Ankara and from Tosya, aba (light fabric woven of camel hair or goat hair, and the garment made from it) from Baghdad, cloth from Harput, peşkir (cotton or linen napkins or towels) from Egypt, sashes from Tripoli, aba from Maraş, sheets from Basra and cups from Kütahya.

¹ A unit of volume similar to a bushel, or the receptacle used for this purpose, mostly for wheat.

Another key factor that rendered Diyarbakır commercially significant was the fact that it was one of the eastern customs points of the empire. Especially for merchants from İran or Dagestan, the city stood at an important crossroads. Following the 1830s and 1840s, when the Ottoman Empire was incorporated into Western capitalism, Diyarbekir, too, witnessed large growth in imports and exports, as its markets opened up in line with the principles of free trade.

19th century Diyarbekir can be understood in three distinct economic periods:

• The period of decline, from the 1830s to the 1860s,

• The period of recovery, from the 1860s to the 1890s,

• The period of growth, which then lasted until World War I.

Beginning in the 1830s, the elimination of mir, who autonomously ruled over lands that belonged to themselves since Ottoman Kurdistan became part of the empire, brought both military devastation and political instability to the region, thus significantly damaging trade. From the 1860s on, when the impact of this devastation was now felt to a lesser extent, trade in the Diyarbekir province increased with the added influence of incorporation into Western capitalism.

British consular reports state that in the year 1857, 441 tons of wool, both exported and sent to other Ottoman regions, was the leading product. This was followed by 735 tons of rice, half of it sold to parts of the empire, the other half exported.

Importing goods was of course as important as exports for the Ottoman economy now opening to western markets. Most the clothing came from Europe via Aleppo, many glass products were imported from Germany, while fine woven muslin (butter muslin), cashmere shawls, spices and medical materials came from India via Baghdad. In addition to this, we know that the amount of English cotton yarn used in the Diyarbekir textile industry increased four- to five-fold in the period from 1860 to 1880, and increased a further twofold by the 1890s.

In 1875, the Ottoman State declared a sovereign default, this was followed by famines in the 1880s, the 1877-78 Russo-Turkish War, known as 93 Harbi, and then, the Sheikh Ubeydullah Revolt in 1880, resulting in trade and production shrinking in Diyarbekir until the 1890s. During the recovery period that lasted from 1890 to 1914, wool, silk, mohair, valonia oak and hide formed 40% of all commodities exported out of Diyarbekir. The rest were industrial products and also agricultural and animal products such as butter, rice, sheep and camels, all sent to many regions of the empire. As a result of this recovery, the Şeyhzâde and Gevranzâde families, who in the past centuries had played a significant role in both the administration and tax collection in the city, were replaced by a new group of families, who owned large swathes of land in the city’s districts and were occupied with trade. Leading these Kurdish families that emerged as competition to the Armenian families influential in the worlds of trade and business were the Pirinççizâdeler, Cerciszâdeler and Ekinciler families. In addition to them, there were also the mir [landlords] of the Zirki tribe (who would take the surname Budak following the foundation of the Republic), who had autonomously ruled a region comprising Hazro, Lice and Hani from the 16th century until 1835, and had settled in the city at the turn of the century.

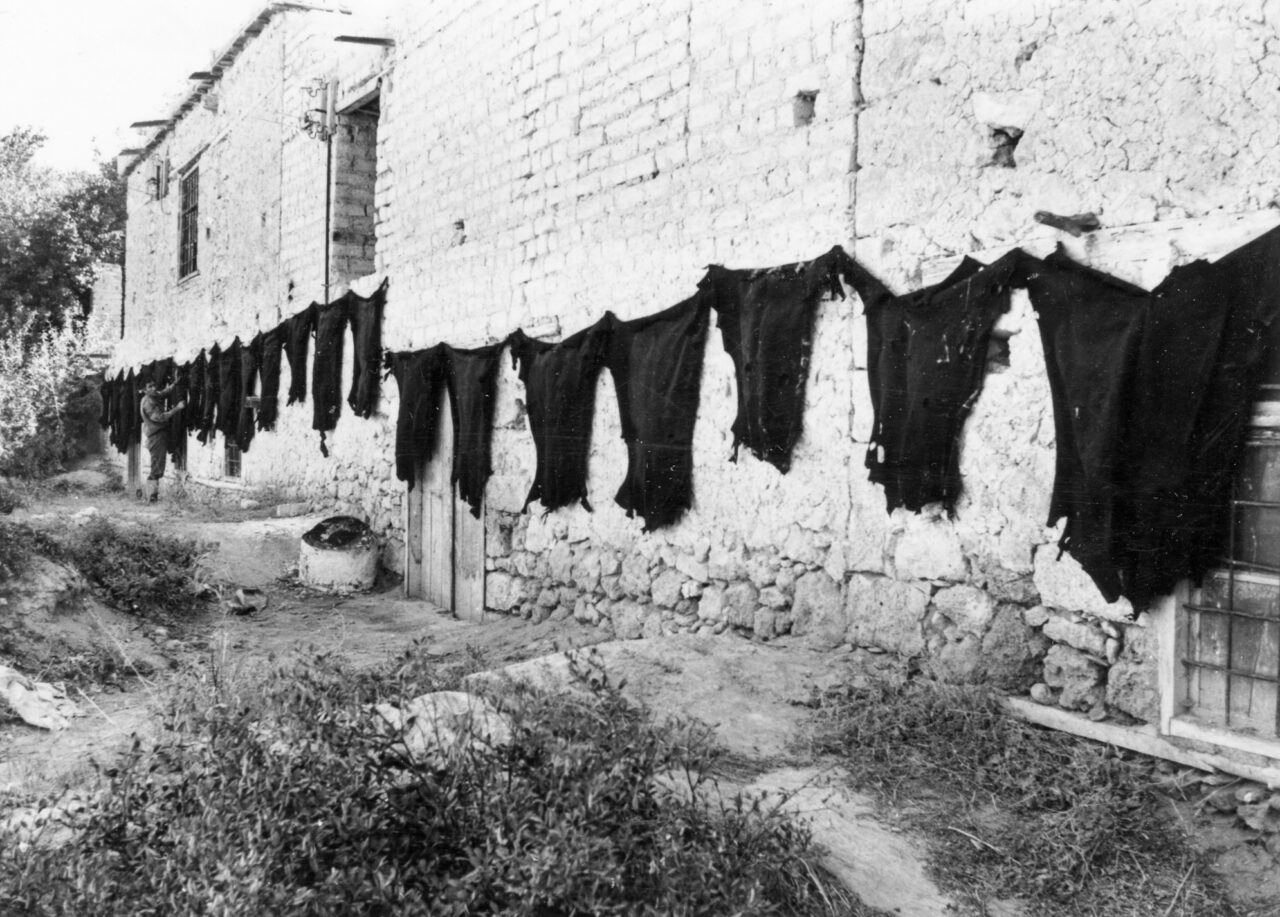

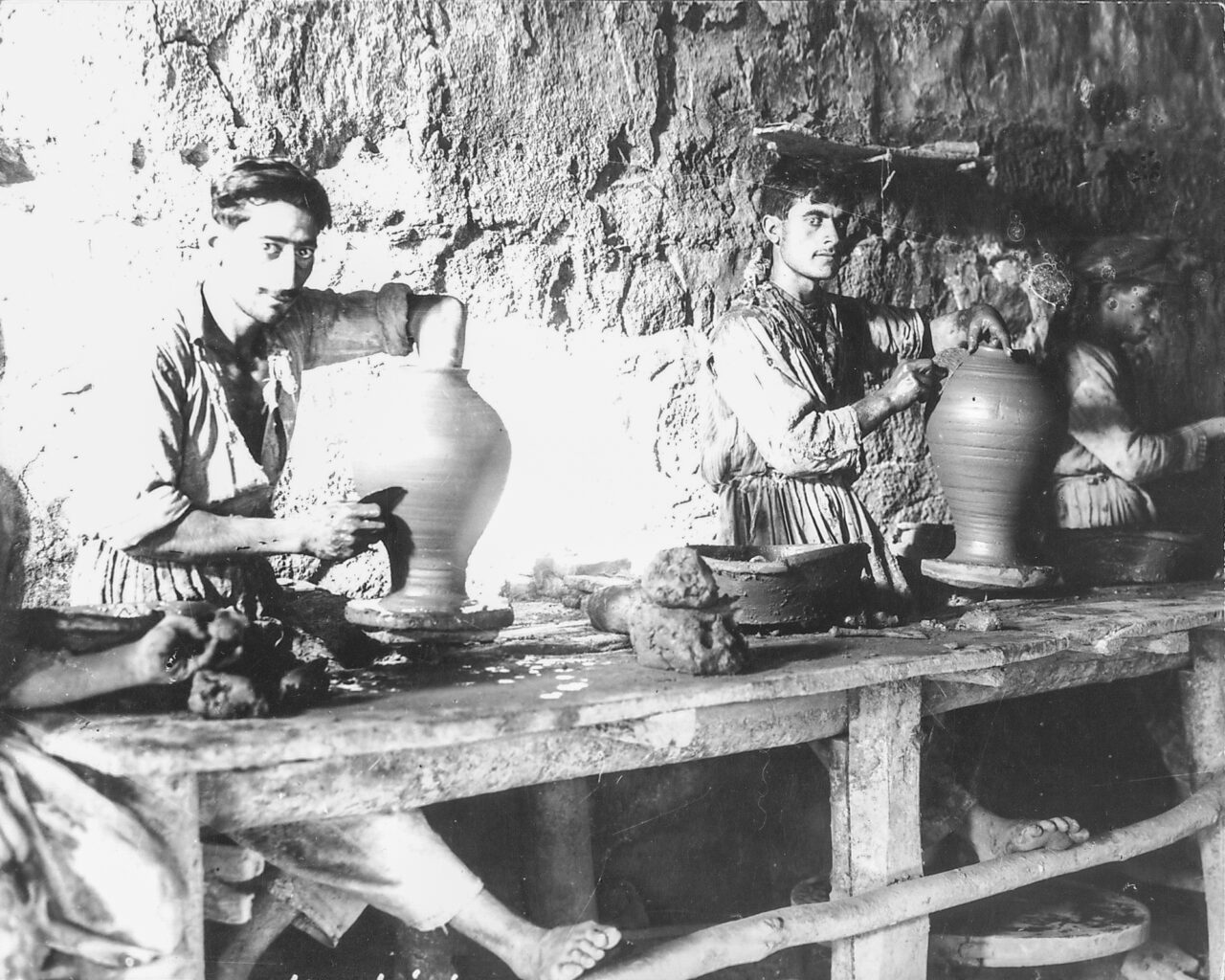

Diyarbekir retained its importance in trade throughout the 19th century, and was also a significant Ottoman city in terms of its production capacity. The observations of British traveller James Silk Buckingham in the 1820s, the main items of production in the city were, first and foremost, silk and woollen clothes, followed by muslin and handkerchiefs, leather in all colours, farrier tools and smoking pipes made of jasmine branch and adorned with gold and silver. There were at least fifteen thousand looms in the city, around five hundred calico printers who carried out their business at Hasan Paşa Hanı, around three hundred debbağ¹ in the leather business and around hundred farriers. There was also a smelter that carried out the smelting work of ore especially from the Ergani-Maden area.

¹ Tanner.

An important item of production in 19th century Diyarbekir was cotton and the textile industry had developed around it. The textile industry was not restricted to mengenehane [centralized textile workshops], but, although not many, there were looms, too, in the homes of people working in this line of work. The red calico made in the city, which was known as kirpas, was well-known in the Istanbul market. Among textile products, gallnut, used in dyeing pure silk and leather, was the leading item.

There had always been an advanced production of cereal crops including wheat, barley, maize, chickpea and lentil in the region. Especially Silvan, from the early modern period to the present day, has been the “granary” of the region. In addition to honeydew melons and watermelons, mentioned first by Evliya Çelebi, cucumbers, grapes, plums, oranges and many other kinds of fruit were grown in the vicinity of Diyarbekir. Viticulture, and thus winemaking had also developed. Armenians and Assyrians led in this specific field of production, while Armenians and Kurds settled in rural areas carried out the vast majority of the rest of the agricultural production.

Livestock breeding, the occupation of the nomadic population in the region mostly composed of Kurdish tribes, formed a further significant part of production. Sheep and goat breeding not only played a highly significant role in the regional economy, but from the 16th and 17th century on, was also important in meeting Istanbul’s meat requirement.

Copperworking and ironworking were two fields of craft that shone especially in the hands of Armenian farriers, however, they faced disruption with the massacres of Armenians that began in Sason in 1896 and spread across most parts of Anatolia, resulting in many surviving Armenians deserting the empire. Then, during the 1915 genocide, not only the artisans in the city, but also people who worked in viticulture and winemaking in the countryside perished. Beside the tremendous suffering, this also meant that the region suffered a great blow in terms of production.

The economic outcome of government policies targeting the Kurds such as enforced settlement and assimilation, implemented from the early years of the Republic, was the underdevelopment of areas where Kurds formed the majority. According to 1927 data, from a total of around 1.4 million agricultural tools and machines, less than 10% was allocated to the Eastern and South-eastern Anatolian regions. The extension of the 1930s’ resettlement policies was the settlement of non-Kurdish migrants in the area and this aggravated the agricultural production issues and in fact, all types of socio-economic problems that the Eastern and South-eastern Anatolian regions had experienced since World War I. From this viewpoint, while Diyarbekir was, according to British consular reports, a region that had, in the 1890s, an exports potential of over 1 million pounds on the interregional scale, by the 1930s, it had regressed to a point that it could only produce enough for the region itself.

The late leap of the economy brought on by the “import substitution industrialization” policy initiated in Turkey in the 1960s had no impact in Diyarbekir; and the city was condemned to agriculture. And since there was no land reform in agriculture, the mechanization that picked up after the 1950s only helped to create large landowners, villages that belonged entirely to the agha and bey. As a result of all these developments, the regional difference between Diyarbekir and the cities in the west in terms of production became more distinct than ever. There are two further reasons for this difference to continue to this day. The first is the conflict that began in 1984 between the army of Turkey and the PKK, and the outcomes of this process. The second is the even greater blow neoliberalism has struck upon agriculture since the 1980s. Under these circumstances, public and private investment has remained at a level that provides no remedy to the long-term economic underdevelopment of the region, and this continues to be the case today.

Text: Dr. Uğur Bayraktar, Historian

Translation: Nazım Dikbaş

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

• Astourian, S. H. (2011) “The Silence of the Land: Agrarian Relations, Ethnicity, and Power”, A Question of Genocide: Armenians and Turks at the End of the Ottoman Empire, (ed.) Ronald Grigor Suny, Fatma Müge Göçek and Norman M. Naimark, Oxford University Press, New York, NY: 55-81.

• Aydın, S. and Verheij, J. (2012) “Confusion in the Cauldron: Some Notes on Ethno-Religious Groups, Local Powers and the Ottoman State in Diyarbekir Province, 1800-1870”, Social Relations in Ottoman Diyarbekir, 1870-1915, (ed.) Joost Jongerden and Jelle Verheij, Brill, Leiden and Boston: 15-54.

• Beysanoğlu, Ş. (1962) Diyarbakır Coğrafyası [The Geography of Diyarbakır], Şehir Matbaası, Istanbul.

• van Bruinessen, M. and Boeschoten, H. (ed.), (1988) Evliya Çelebi in Diyarbekir: The Relevant Section of the Seyahatname, E.J. Brill, Leiden and New York.

• Buckingham, J. S. (1827) Travels in Mesopotamia Including a Journey from Aleppo to Bagdad by the Route of Beer, Orfah, Diarbekr, Mardin & Mousul, Vol. 1, London.

• İzmir Fuarında Diyarbakır [Diyarbakır at the İzmir Fair], Diyarbakır Ticaret ve Sanayi Odası [Diyarbakır Chamber of Commerce and Industry], Diyarbakır, 1938.

• Erinç, S. and Tunçdilek, N. (1952) “The Agricultural Regions of Turkey”, Geographical Review, 42(2): 179-203.

• Hovannisian, R. G. (ed.), (2006) Armenian Tigranakert/Diarbekir and Edessa/Urfa, Mazda Publishers, Costa Mesa, CA.

• Quataert, D. (1993) Ottoman Manufacturing in the Age of the Industrial Revolution, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

• Yadırgı, V. (2017) The Political Economy of the Kurds of Turkey: From the Ottoman Empire to the Turkish Republic, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

• Yılmazçelik, İ. (1995) XIX. Yüzyılın İlk Yarısında Diyarbakır (1790-1840) [Diyarbakır in the First Half of the XIX. Century (1790-1840)], Türk Tarih Kurumu, Ankara.

EXHIBITION CREDITS

Contributing authors

Dr. Mehmet Atlı, Levon Bağış, Dr. Uğur Bayraktar, Prof. Dr. Gültekin Özdemir, Prof. Dr. Aslı Özdoğan

Exhibition editor

Pınar Öğünç

Translation

Ekrem Yıldız, Murat Bayram, Selamî Esen (Kurdish)

Nazım Dikbaş (English)

Design

Fika

Publication date

April 2021 / November 2021